Nick Mohammed in "Ted Lasso" (Apple TV+)

Eighteen months after the writers' and actors' strikes of summer 2023, the television landscape remains inchoate, to say the least. Networks finally confronting the fact that streaming is not a viable business model are producing far fewer shows, and many of those being made feel like throwbacks, or like movies that were reimagined (for better or for worse) as limited series.

But amidst the chaos of an industry trying to regain its footing, one fascinating trend that has emerged among popular shows is a focus on pastoral care.

Advertisement

When "Ted Lasso" first debuted on Apple TV+ in August of 2020, it presented itself as a "fish out of water" comedy. American football coach Ted Lasso (Jason Sudeikis) comes to England with his assistant Coach Beard to manage an English soccer team, despite having absolutely no knowledge of the game or the nation.

With a country accent as thick as his mustache and an insistent belief in people, even when they treat him with derision, Lasso charms his club and audiences alike. In its first season, the series was nominated for 20 Emmys, the most ever for a first-year show, and won seven, including Best Comedy Series.

At the start of the second season, after star player Dani Rojas (Cristo Fernández) accidentally kills the team's mascot during a game and subsequently finds himself unable to kick a ball accurately, management brings on a sports psychologist, Dr. Sharon Fieldstone (Sarah Niles). Unexpectedly, the show deepens into a heartfelt and poignant exploration of trauma and recovery. The arrogant ace turns out to be tormented by a vicious drunk of a father. Team owner Rebecca Welton (Hannah Waddingham) faces relentless public humiliation from her ex-husband. And Lasso himself is haunted by his father's death in his youth, and the way his mother responded.

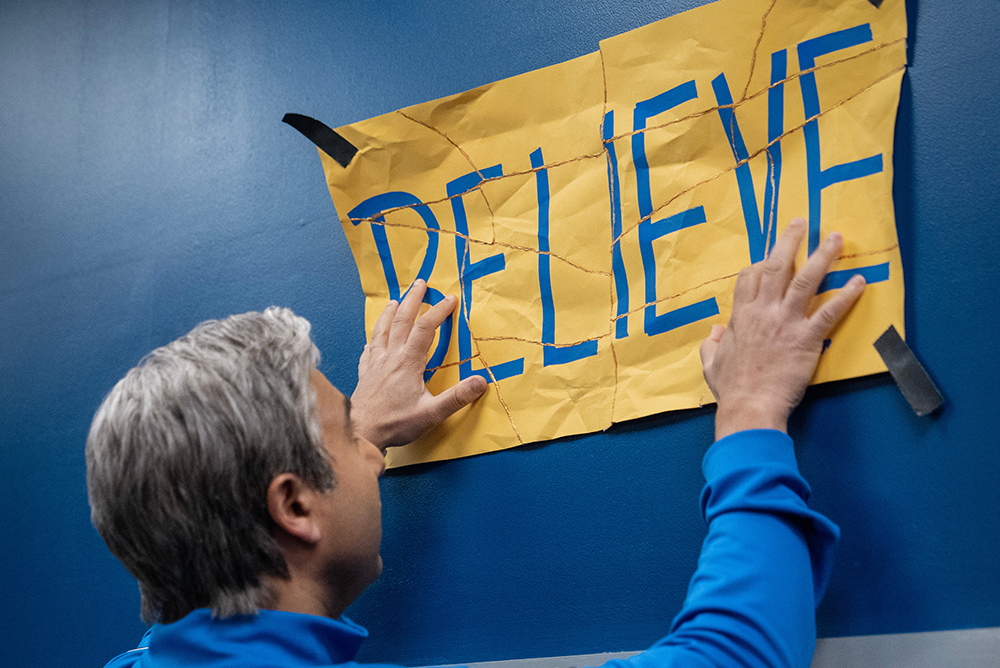

In the pilot episode, Lasso puts up a simple sign in the locker room: "Believe." By its finale, the show is a profoundly observed (and yet still funny) story of a group of people confronting the parts of their history which undermine their capacity to do so.

Jason Sudeikis, right, appears with Brendan Hunt in a scene from the TV show "Ted Lasso" streaming on Apple TV+. (CNS/Apple TV )

When "Ted Lasso" began winding down, its co-creator Bill Lawrence and star Brett Goldstein produced a new series with actor Jason Segel that was even more direct in its interest in pastoral care. "Shrinking," which debuted on Apple TV+ in January 2023, tells the story of a three-person therapy practice in Los Angeles in which one of the therapists, Jimmy Laird (Segel) has fallen apart after the death of his wife. Despite its dark subject matter, "Shrinking" too leads with humor, as Jimmy begins intervening in his patients' lives in inappropriate ways and to unexpected consequences. After he suggests to a patient with an abusive boyfriend that she metaphorically push him off a cliff, she takes his advice literally.

But just as in "Lasso," the show's real interest is in digging into the underlying issues of its characters — the unending need of Jimmy's neighbor Liz (the great Christa Miller) to butt in; his co-worker Gaby's drive to be with guys who need to be fixed; their boss Paul's incipient Parkinson's disease; and Jimmy's daughter Alice's trauma over the death of her mother and her father's subsequent breakdown. And once again, the characters' recovery comes about through a combination of professional pastoral care in the form of conversations with one of the therapists on the show and their friendships. More than once I've written down a piece of advice given on the show, because it felt so helpful.

Jason Segel and Jessica Williams play friends and co-workers in "Shrinking." (Apple TV+ photo)

I've had a similar experience watching the new medical show "The Pitt" on HBO Max. Co-created by "E.R." producer John Wells and its star Noah Wyle, "The Pitt" follows Wyle's Dr. Michael "Robby" Robinavitch through a day running the ER at an underfunded, overwhelmed Pittsburgh public hospital. Each episode brings the next hour of Robby's 15-hour day, which sounds like a bit of a stunt in the abstract but ends up dramatically deepening the kinds of stories that one usually finds on a medical show.

Rather than being rushed out by the end of the episode, middle-aged siblings confronting their dying father's end of life directive or parents dealing with the likely brain death of their child are allowed the space for their stories to develop in much more realistic ways. The siblings get a whole episode just to struggle with the directive and another to watch their father die. The parents of the seemingly brain-dead child are afforded episodes to push back against that diagnosis. A girl who almost died of an overdose gets time not simply to get better but to face her near death experience. The hour-by-hour approach of "The Pitt" favors a more radical empathy for those in the hospital.

Though he is the head doctor, Robby also serves as a sort of chaplain, providing unnecessary tests to the parents of the brain-dead child simply to give them time to confront the reality of what has happened, and advising the siblings on how to say goodbye to their father. He tells them there are four simple, key things to say that can really help: "I love you. Thank you. I forgive you. Please forgive me." It's the best pastoral suggestion I've ever heard for that situation.

"The Pitt" follows Noah Wyle’s Dr. Michael "Robby" Robinavitch through a day running the emergency room at an underfunded, overwhelmed Pittsburgh public hospital. (Warrick Page/HBO Max)

But these shows and others … are invested in telling stories about recovery and freedom with real pastoral wisdom. It's a remarkable trend, one to celebrate.

"The Pitt" has such a clear investment in presenting its story in a realistic approach, it's a little surprising that the show thus far has not used a chaplain. (It still has nine episodes, so there's still lots of time.) But in a sense, that's a striking quality about this genre; while they're deeply invested in presenting a world in which people can find healing, the potential role of religion, faith or some version of a divinity in getting to that state goes largely unexplored. Robbie asks whether the siblings believe in God — which is itself a thousand times more than almost any other medical show ever does — and the sister replies emphatically, "Oh God, no. No God."

There's lots of potential reasons for the absence of religion in these kinds of shows, from a lack of ready comfort on the part of writers with the practices of different faith to a resistance to show any kind of support for institutions that express certain moral stances. But these shows and others — "The Bear," "The Last of Us" and "Severance" also come to mind — are invested in telling stories about recovery and freedom with real pastoral wisdom. It's a remarkable trend, one to celebrate.

And perhaps the success of these shows in an otherwise struggling media landscape will encourage Hollywood to consider the story potential of hospital chaplains, spiritual directors and pastors as well. Big twists and big explosions can take you far, but people today seem to be yearning for grounded stories that offer the possibility of healing, forgiveness and redemption.