In this image from the PBS documentary series "Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland," Anne Marie, 10, throws bottles at British troops during a riot in Belfast, Northern Ireland, in 1981. (PBS/Courtesy of Magnum Photos/Peter Marlow)

"I hate to ignore the things I'm not comfortable with, because they're important."

So says an ex-paramilitary soldier featured in the new PBS documentary series on Northern Ireland's 30-year civil war, known as the Troubles. And indeed, "Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland" is not comfort viewing. I say that not only as a caution, but also as a recommendation.

The five-part series began streaming on PBS.org and the PBS app on May 22, with a nationwide broadcast premiere on Aug. 28. The episodes follow the Troubles chronologically, beginning in the late 1960s, when religious segregation and social disparities between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland sparked a civil rights movement and sectarian violence that claimed the lives of more than 3,600 people. It ends its story in 1998, when a multiparty peace deal known as the Good Friday Agreement received overwhelming support in a voters' referendum.

The series is directed by James Bluemel, whose previous work includes the award-winning "Once Upon a Time in Iraq," about the Iraq War, and "Exodus: Our Journey to Europe," about the Syrian refugee crisis. Like his Iraq War documentary, "Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland" is told through the eyes of ordinary people who lived through a bloody sectarian conflict. Their testimonial-style interviews are interwoven with archival footage, some of which is disturbingly graphic. The footage also contains moments that are so dramatic and that the Troubles almost play out like a stark, hyper-violent movie. Indeed, one person interviewed uses those very words — "it was like a movie" — to describe the war's early days, before anyone had any idea how long it would last or how much blood would be shed.

Meanwhile, the series title evokes the power of storytelling. The phrase "once upon a time" may suggest a conflict in the distant past, but immediately we see how present the war still is to the people telling their stories. Many of the people interviewed were young children or teenagers at the start of the war. Their stories bear witness to war's damaging impact on youth and how the Troubles irrevocably altered their individual lives as well as their families and communities.

In an interview in the PBS documentary series "Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland," Fiona, whose brother Jim was killed by a British soldier, recalls representing the city of Derry in a Miss Ireland beauty pageant 1986. She said she put on an act around the other contestants, who didn't know her brother had been murdered. (PBS/Courtesy of Gus Palmer)

In the first interview, we hear from a woman named Fiona, whose brother was in the Irish Republican Army, or IRA, a Catholic-identified paramilitary group that sought to end British rule in the north and bring about a united, independent Ireland with the island's southern half. Settling in a chair to speak, Fiona is visibly nervous. Suddenly, someone hands her a laptop and she's confronted with a video of herself in the 1980s, back when she represented the city of Derry in a Miss Ireland beauty pageant. She bursts out laughing, commenting on all the excessively poofed-up '80s hair.

Reminiscing on the pageant, however, Fiona says she "put on a character" when she was around other contestants. "No one knew my brother was murdered," she said. "None of them." It's a compelling series of moments that sets up a complex journey of emotions, memories and secrets throughout the series.

Bluemel, who is British, recruited Northern Irish filmmakers such as Sian McIlwaine and included a variety of perspectives for his interview segments. Other than the final episode, which details the path to peace that involved the Irish, British and American governments, we see few "talking heads" segments with politicians or commentators. Instead, we hear from everyday people: Catholics and Protestants; ex-paramilitaries and former British soldiers; adults left widowed and children left fatherless or motherless because of the war; people who supported the peace agreement and people who voted against it. It is sometimes surprising how some of these identities overlap in ways that defy easy categorizing.

Religion may be the most uncomfortable topic of all.

Despite the emotional pain evident the interviews reveal and the grim cyclical violence, the series shares stories of people overcoming the division in their communities. In one episode we hear from Terry, a music lover in Belfast who opened a record store in the 1970s. By then, the violence in his home city had become a norm. He had lost friends and had been threatened by paramilitaries himself. "So I decided, I’m going to do something before they kill me," he says. His record store became a place that brought music lovers of both religious affiliations together, "a little oasis in a sea of madness."

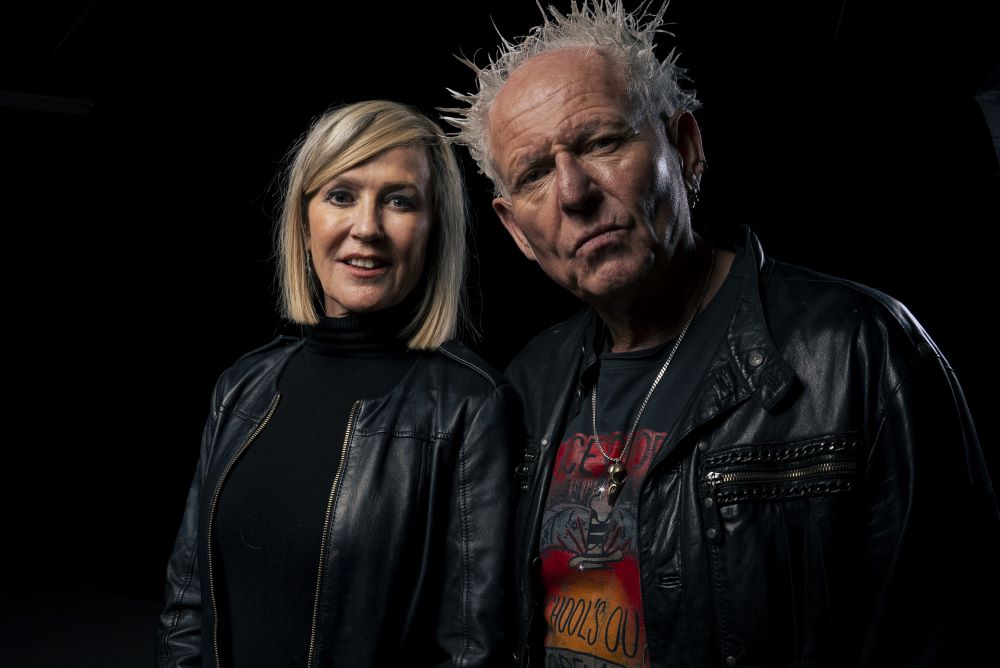

We also hear from Greg and Yvonne, a couple in a "mixed marriage" (in Northern Ireland, this refers to a marriage between a Catholic and a Protestant) who met in a gritty punk bar in Belfast. For many of the bar's regulars, it was the first chance they got to meet someone of a different religion or background. Punk music also attracted young people from areas that were heavily controlled by paramilitary groups. Through punk's aggressive sound and lifestyle, fans found common ground, a creative outlet for their anger and confusion, and an escape from the divisiveness of their communities.

Greg and Yvonne, featured in the PBS documentary series "Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland," met in a gritty punk bar in Belfast during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. For many of the bar's regulars, it was the first chance they got to meet someone of a different religion or background. Punk music attracted young people from areas that were heavily controlled by paramilitary groups. (PBS/Courtesy of Gus Palmer)

Later we meet Patrick, whose father was murdered after refusing to pay protection money to the paramilitaries that controlled his community. In the early 1990s, Patrick channeled his painful experiences into stand-up comedy and opened a comedy club. He describes how laughter can work as a healing balm, avoidance strategy and survival tactic all at once. "The sense of humor is very strong in Northern Ireland, 'cause if you're being funny, you didn't have to talk about yourself," he said. " 'Cause nobody wanted to answer the question, 'How are you?' And then there was also that thing of, 'Well, if I am living, we have to live.' "

Stories like these keep coming around to that important discomfort — and religion may be the most uncomfortable topic of all. Most interview subjects identify themselves by their religious background, but not many of them discuss their faith in terms of the strength or comfort it offered them during the Troubles. After one atrocity, John, a Protestant in Belfast whose family harbored a secret about his mother, says, "From an early age I did believe in God. But when these soldiers were attacked, that was the most horrendous thing I'd ever seen in my life. It was one of those moments that made me stop [and ask] what kind of God would let this madness go on."

Early on, we see an example of Christian charity (and neighborly competition) as both Catholic and Protestant women in Derry and Belfast are shown bringing tea and biscuits to the British soldiers patrolling their communities’ streets. But as the series goes on, the moments of grace become less facile. An ex-paramilitary member talks about devoting his life to peacebuilding after serving prison time for planting a bomb. Another man gives up his paramilitary involvement for the sake of his marriage and family, who suffered considerable strain.

Several stories make plain the long struggles with rage and the difficult road to forgiveness. Some interviewees describe how they directed their pain toward campaigns for truth and justice for their murdered family members. Even the stories of those still skeptical of the current state of peace convey tremendous integrity and dignity.

Advertisement

In the final episode, we hear a testimony of intentional forgiveness. Richard, who grew up in the Catholic section of Derry, tells of being shot by a British soldier when he was a child. Many years later, he tracked the soldier down to request a meeting. It wasn't what he expected. But that didn't mean grace was off the table. "If we want reconciliation," he said, "you can't meet the person that you would like to meet. You've got to meet them for who they are."

For Richard, happiness came from working to form a friendship with the soldier, even if forgiveness didn't come easy. Maybe the effort is the point. A scene showing the two men reuniting at the site where one shot the other is unforgettable — heartbreaking, uncomfortable and courageous.

In one of the most painful moments of the series, one person recalls the indifference he encountered while living abroad in England when the Good Friday Agreement passed. No one there cared. Hopefully, this documentary will find viewers of a different mindset in the United States. It may be difficult to watch. But how much more difficult is it to survive war with both your dignity and a commitment to peacebuilding intact? The stories in "Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland'' are brave, important and necessary to hear. This is essential viewing.