"St. Augustine in His Study" (shortly after 1502) by Vittore Carpaccio. Scuola Dalmata dei Santi Giorgio e Trifone, Venice. (Photo by Matteo De Fina)

Vittore Carpaccio's "St. Augustine in His Study" would make first-rate "Where's Waldo?" fodder. In the large painting, dated around 1502, the saint — per legend — realizes he is penning a letter to a man who has just died: St. Jerome.

Carpaccio peppers the scene with books, ecclesiastical paraphernalia, sculptures, an hourglass, and a shell, among other objects. It's such a more-is-more picture that one is liable, as I admit I did, to miss one of the most mystifying design elements in art history.

On opposite walls, two furry arms bear sconces, or lamp holders.

"It looks like the arm of a yeti, an abominable snowman, holding these sconces up on the wall at left and right. What the heck? Where did that come from, because everything else is so detailed and precise," Gretchen Hirschauer, the National Gallery of Art's Italian and Spanish painting curator, told NCR in an interview. "I always try to point them out, and people say, 'Oh my God.' "

One learns early on in the National Gallery's major exhibition "Vittore Carpaccio: Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice" (through Feb. 12) — evidently the artist's first retrospective out of Italy — that there is equal danger of over- and under-interpreting Carpaccio's extensive details, whether plants, animals, birds, architecture or costume. Sometimes a bird is more than a bird; other times, a plant is merely a plant.

If the painter intended the yeti-like arms to be significant, my best guess is he meant either to evoke exotic, African animals of Augustine's Hippo (present-day Algeria) or to reference the saint's writings in The City of God about rational man's dominion over irrational beasts. A more remote possibility might be reference to the trade of the artist's father: furs and leather. Carpaccio (circa 1460-1525/1526), of course, was unavailable for interview.

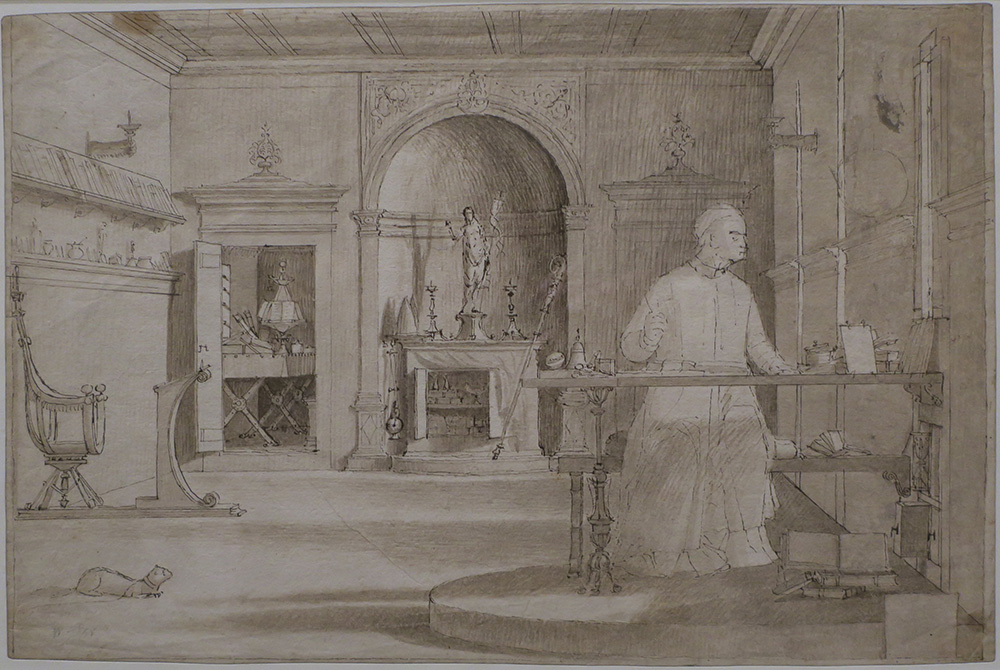

"St. Augustine in His Study" (circa 1502-1504) by Vittore Carpaccio. British Museum, London. (Photo by Menachem Wecker)

Carpaccio's name is likely new to many readers, but this painter of altarpieces and other frequent religious subjects is very important. He seems to have trained with the renowned Bellini brothers — Gentile and Giovanni — and 19th-century English critic John Ruskin promoted his work and even called Carpaccio's "Two Women on a Balcony" (1490-95) "the best picture in the world." (Although it is a masterpiece, many, including I, beg to differ.)

Elaborate details are one of Carpaccio's signatures, and anyone who has donned glasses with too strong a prescription knows something of how Carpaccio may have seen the world. Happily, his insatiable appetite for precise detail laid breadcrumbs from which scholars are learning many things, from how and where Renaissance Venetians displayed devotional images to the degree of comfort Christians had with pagan art and objects at the time. Those who want to know more will want to consult the exhibit's comprehensive catalog.

In the painting of Augustine's study, another element is noteworthy, and this one was intended to be symbolic. It is a special treat to see the painting juxtaposed with Carpaccio's preparatory pen-and-ink drawing (1501-1508, British Museum) in the exhibit. In the drawing, a small ermine looks up, considering the saint. A kind of weasel, this animal symbolized purity, as in Leonardo da Vinci's "Lady with an Ermine" (circa 1489-91), and was said to prefer being captured and killed to escaping across a muddy field, dirtying its white fur.

The painting substitutes a dog — symbolic of fidelity — for the ermine, and infrared scans reveal Carpaccio originally painted an ermine before opting for a canine symbol. Both the drawing and painting display dramatic light and shadow, as Carpaccio decided how to depict the miraculous light, which tipped Augustine off to Jerome's passing.

Detail of the dog (with hint of painted-over ermine) in Vittore Carpaccio's "St. Augustine in His Study" (shortly after 1502). Scuola Dalmata dei Santi Giorgio e Trifone, Venice. (Photo by Menachem Wecker)

Frederick Ilchman, chair of European art at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, noted in an interview that the painting contains a proto-museum. (Ilchman also chairs Save Venice, a U.S. nonprofit devoted to preserving Venetian heritage, including funding conservation of about 20 Carpaccio works, which allowed three large canvases to travel to Washington, D.C., for the show.)

In the back of the room on the left, one can see Augustine's intimate studiolo (study), wherein he would read, pray, write and store small treasures. "A host would bring just one or two guests to admire these books and little artworks," Ilchman said. Scholars think the studiolo merged monastic cells with secular treasuries of the wealthy, which eventually developed into the 16th-century curiosity cabinet, called a kunstkammer. "Eventually, such big and ambitious rooms get the term 'museum' as in a place of the muses," Ilchman said.

Carpaccio's extensive details in this and other pictures and the detailed narrative paintings of his peers amount to what Princeton University professor emerita Patricia Fortini Brown refers to as "eyewitness style." The idea is that viewers would have found troupes of supporting actors and exhaustive detail compelling witnesses that testified to the truth of the subject matter.

"Very specific details of architecture, costume, accessories, animals and more are all marshalled by the artist to proclaim the veracity of the miracle itself," Ilchman said. "Seeing is believing."

Carpaccio's circa 1504-1507 painting "St. George and the Dragon" comes to Washington from a devotional Venetian confraternity with medieval roots. Saint and beast fill the composition, but more than a dozen human and animal skulls and several full and partial corpses scatter along the foreground, where animals feed on the remains — presumably dragon victims. Extensive vegetation, both Christian and Islamic-styled buildings, a host of people, and several ships fill the horizon.

"St. George and the Dragon" (circa 1504-1507) by Vittore Carpaccio. Scuola Dalmata dei Santi Giorgio e Trifone, Venice. (Photo by Menachem Wecker)

Beholding the wall-sized picture in person, it is easy to imagine Carpaccio's contemporaries might have considered it a kind of documentary.

"Holy figures like the Virgin Mary wear contemporary Venetian fashions. biblical events are often set in the Venice of his day, with architecture that would look familiar," Hirschauer said. "His sacred paintings are filled with Venetian ships, like those galleys that were built in the Venetian ship building area called the Arsenale, or paintings may include smaller merchant gondolas."

Carpaccio also depicted mosques, palm trees and people wearing Jewish and Muslim clothing to suggest the Holy Land, she added.

He had in mind the kind of thing we might call "diversity" today, which reflected Venice's cosmopolitan nature at the time.

"It was teeming with foreigners, and of course products from around the world were traded by the merchants of Venice. Carpaccio's paintings reflect this amazing diversity of cultures," Ilchman said. "We might think that in 2022 we are living in an unprecedented urban and multiethnic society, but Carpaccio reminds us that Venice accomplished this far earlier."

Advertisement

In "Miracle of the Relic of the Holy Cross at the Rialto Bridge" (circa 1496), from Venice's Gallerie dell'Accademia, Carpaccio portrayed both a miracle transpiring, and "incidental detail such as laundry hung out to dry, the rooftop altana where a maid is beating a carpet, and the characteristic Venetian chimneys," Deborah Howard, emerita architectural history professor at St. John's College, Cambridge, writes in the catalogue.

The laundry reminds Hirschauer of the artist Piero di Cosimo (1462-1521), who was also a glutton for detail. "That was one of his signatures. If you can see some laundry hanging out the window in the far distance, you knew that that was Piero," Hirschauer said.

She thinks Carpaccio takes the grand, accurate depictions of Venice "to a whole other plane," although other artists like the Bellinis also depicted similar subjects. And Carpaccio was on the cusp, as the next generation of Venetian painters, most prominently Titian (1488/1490-1576), Tintoretto (1518-94), Paolo Veronese (1528-88) took painting in a very different direction.

"This is how he sees the world, and he has this amazing interest in detail, costume and texture of these beautiful brocades," Hirschauer said. "He just does these better than anybody at the time."

Carpaccio could not have anticipated the increasingly granular detail that we can capture with our smartphones — each phone "generation" with a fancier camera than the next. I ran a theory by Hirschauer, that Carpaccio can teach us both how to transcribe detail and how to arrange it with underlying compositional structure, which for the religious painter must have been connected to transcendent meaning. She agreed.

"That's exactly what he's hoping to achieve," she said. "To get people to see that there is some unifying divine plan here."