Paradise Harbor, Antarctica (Wikimedia Commons/Liam Quinn)

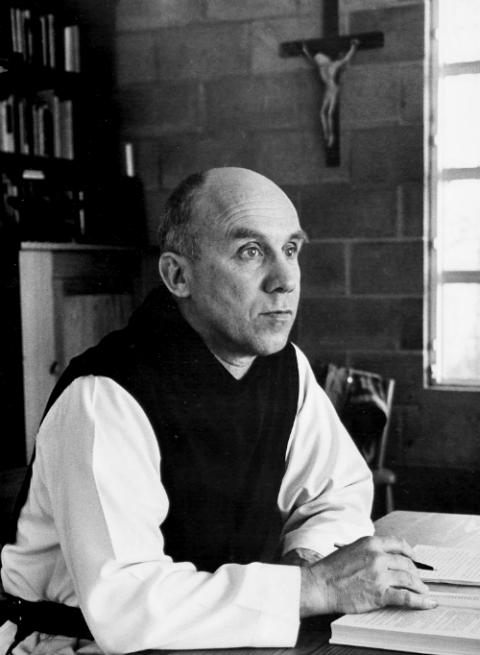

During Lent, Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton was irate when the Passion was read in what he described as an "extremely trite and pedestrian English version," albeit one approved by the American bishops. He called it "liturgical vaudeville."

A complex, multifaceted individual, Merton had many illustrious friends whose views at times conflicted with those of the church. These included the peace activists Frs. Daniel and Philip Berrigan, and the Nicaraguan freedom fighter Ernesto Cardenal.

As a Trappist monk, Merton lived under a rule of silence at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani — and for a time on the grounds as a hermit. But while the other monks made cheese and fruitcake, Merton, who studied English at Columbia University, was encouraged by the abbot to write.

He wrote more than 60 books, including his bestselling autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, parts of which were suppressed because of references to youthful sex and drinking. Censors made caustic remarks about Merton's style, and early versions of the book were denied a nihil obstat, or official church approval. One individual even advised Merton to take a grammar correspondence course. But most professional writers, including Graham Greene and Clare Boothe Luce, wrote glowingly about the book.

Fr. Thomas Merton (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

In On Thomas Merton, award-winning author Mary Gordon probes Merton's "dual identities" of priest and writer. She discusses The Seven Storey Mountain, his novel My Argument With the Gestapo, and his journals, which included Merton's comments on his epiphanies, mystical insights, his poor health, his problems with writing, his criticism of liturgical inadequacies, and his fury at the church's materialism and commercialism.

Gordon analyzes Merton's themes, style, subjects and writing as she quotes liberally to prove her arguments. Merton often felt that his writing violated the spirit of his vocation. He was, however, a compulsive writer. As he put it, "I am simply surfeited with words. ... I feel like a drunk and incontinent man falling into bed with another whore. ... The awful thing is I cannot stop."

According to Gordon, Merton had a gift for bringing a place alive through descriptive writing. Some of the prose passages that Gordon quotes are evocative and could be considered prose poems. She praises My Argument With the Gestapo and its style of writing, comparing it to work by Joseph Conrad and Graham Greene in passages like this: "I will write about the small room I once slept in, one that smelled of fog and quilts. ... All night long, I could hear water murmuring in the pipes in the wall, and the voices of old ladies came through the frail locked door."

A flaw in Gordon's book, though, is her treatment of Merton's poetry, which she says isn't as good as that of Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell and others of his generation. Yet she admires his metaphors and similes and the way he brings two contrasting ideas together. She also ignores the praise many of his poems received from poets like Lowell who, writing for Commonweal, called Merton "the most promising of our American Catholic poets."

Gordon is best when she shows Merton as a divergent thinker who felt compelled to share his thoughts on everything from social justice, war and nuclear weapons to the contemporary Catholic Church's lack of aesthetic taste.

It irked Merton when statues of the Virgin Mary resembled a Hollywood actress and when the abbot referred to Jesus Christ as our "best buddy" or the "trader" of Galilee.

He approved of the Second Vatican Council but was outraged because the church, which had centuries earlier been responsible for inspiring the world's best art and culture, was now satisfied with "the worst art, the worst writing, the worst music, the worst everything that has ever made everybody throw up."

Ultimately, Gordon's thought-provoking book makes Merton's anger palpable — as well it should.

Barbara Brown Taylor's somewhat overly ambitious book contains a little of everything as she tries to describe finding God through her own experiences and those of other people, including many of her students.

Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others is part memoir of her classroom encounters teaching religion, part study of world religions, part philosophy, and part musing on religious experiences. The book includes profundities from international spiritual luminaries like Rami Shapiro ("What you need is the God just beyond your understanding") and Merton ("God speaks to us in three places: in scripture, in our deepest selves, and in the voice of the stranger").

Her students at Piedmont College in Georgia (which Taylor, quoting Flannery O'Connor, refers to as the "Christ-haunted South") are from various religious backgrounds. Some are Hindu, evangelical, Baptist, Anglican, Protestant, Catholic, Muslim, Mormon and pagan. Some are atheists. Some took her course because it fulfilled a requirement in their major. Others had heard that Taylor was an easy grader. A very few seemed genuinely interested in learning about religious theologies other than their own.

Religion 101, Taylor says, wasn't only about world religions and their commandments, theologies and prayers in Sanskrit, Hebrew, Arabic and Greek, or about terms like stupa, mandir and minaret. Nor was it merely about facts, like the story of Estevancio of Azamor, who survived a Spanish shipwreck in 1528 and was the first documented Muslim to come to the United States. It was actually about expanding her students' — and her own — idea of the divine by learning about other religious traditions.

Taylor includes her own anxieties about dealing with the wilderness experience (reminiscent of Jesus' 40 days in the desert) as well as studying religions that seemed opposite to her own Episcopal Christianity. She shares her practical worries about young people dropping her course because they felt it threatened their own religious views. She even describes her concerns about creating a final exam that adequately measured the spiritual growth that she hoped students would experience as a result of taking her course.

Ultimately, Taylor believes that while all religions are not the same, the differences among religions can, if nothing else, widen people's understanding of God. Her point is well-taken.

If it's true, as Merton said, that one can find God in our deepest selves, Jean McNeil's experience in British Antarctica is a case in point. She spent four months there as part of a group studying climate change.

Ice Diaries: An Antarctic Memoir is a compelling record of what she learned — both about the planet and herself. Both a witness statement and travel diary, this award-winning book has recently come out in a second edition.

In McNeil's opening pages, she muses about the word apocalypse and its original meaning of uncovering. She suggests that her goal is to uncover the meaning of winter as it applies to the Earth and to her own sense of self. By book's end, she has.

She studied ice formations and how to interpret them. She explored areas outside of the base and learned to fly a plane. She studied the few birds, fish and seals that inhabit the area during the summer. She learned about climate change and how global warming is threatening life in Antarctica and, by extension, everywhere else on Earth. She found out that although the most radical effects of climate change are in the Arctic where "the melt season has lengthened by more than a month since 1979," the western Antarctic is behaving much like the Arctic.

Advertisement

The book is also a reminiscence of McNeil's growing-up years in which she notes her Roman Catholic background, saying she felt little connection to the religion. Her mother dragged her to Mass, she says, "enraged by the natural reluctance she sees in me for religion." Yet by the end of McNeil's sojourn in the Antarctic, she had become as she suggests, "religious at heart."

She has several epiphanies that she shares in stunning descriptive detail. Two of them occur at the cross near the monument to those who died at the Antarctic. The scene is reminiscent of one at Calvary. Standing there and watching the sun that never sets, she notices "the orange flutes" of the sun, like "church spires had been buried in the ice, just beyond the visible horizon ... Light was refracted upwards through them."

McNeil also alludes to work by poets who inspire her, including Sappho, Anne Carson, William Wordsworth, whose thoughts about cosmological experiences shape her own, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, especially "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner," which she quotes in its entirety.

Ultimately, she attempts to understand the ineffable, especially as it applies to the Antarctic wilderness and its effect on her life. She discusses the conscious and unconscious mind, the meaning of her dreams and intuitions and the possibility of reincarnation.

Filled as it is with musings about the existence of God, free will and humankind's responsibility to be stewards of the Earth, the book raises difficult questions. But, as McNeil suggests, those questions are well worth considering.

[Diane Scharper is a lecturer at the Johns Hopkins University Osher Institute. She is the author or editor of seven books including, Reading Lips and Other Ways to Overcome a Disability, winner of the Helen Keller Memoir Competition.]