Harbor in Leticia, Colombia, July 2012 (Wikimedia Commons/Pedro Szekely)

From the sky, the forest below spreads like a vast green sea. On the ground, the heat hits like a sucker punch. In a few hours, I am walking a trail with a native guide from the Jívaro tribe of Peru amid the lush foliage of the Colombian Amazon, so dense it's impossible to see more than a foot on either side.

Frogs croak and unseen animals scuttle here and there, but for hours there is no sign of human settlement. Yet scattered throughout the greater Amazon basin, an expanse of 2.5 million square miles that stretches across the territory of nine countries, live some 30 million people.

Coming out of the forest days later, the first ping from my cell phone, quickly followed by the drone of power saws cutting wood for new houses and the harsh swishing of a cement mixer creating pavement for a road, are signals that we have crossed into another kind of Amazon, growing with newcomers and new technology.

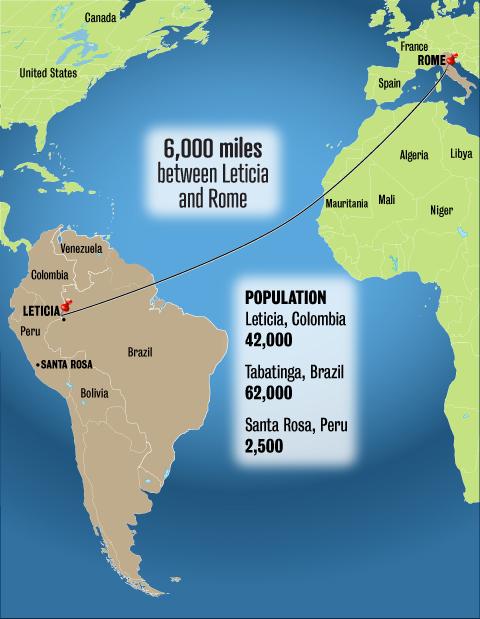

More than 6,000 miles away, at the Amazon synod in Rome, bishops, clergy and lay people — including indigenous representatives — are shaping a blueprint for the Catholic future of the region, remote but rich with God's creation.

The Amazon is home to some 400 native tribes, some whose populations are nearing extinction as they number fewer than 500 people and others whose ranks number in the thousands and are thriving. Plant life includes some 390 billion trees in rich diversity — 16,000 species.

The region also presents a gift of survival to every person on earth, absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen, acting as a brake on climate change. But it's a gift at risk.

The year after Colombian peace accords were signed in 2016, deforestation went up 44% in massive areas formerly controlled by guerrillas, according to Colombian author Pablo Correa, who writes on science and the environment for the Bogota newspaper, El Espectador. The region is under threat from the global appetite for steak and hamburgers — cattle ranching — and extractive mining.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

People here are hoping that the synod will recognize that the more that Amazon residents can control their own resources, and the young are encouraged to stay and carry on traditions of preserving an ecologically sound way of life, the greater chance for the Amazon to survive.

Adriana Parenti, who belongs to the Ticuna tribe, typifies the growing number of Amazon natives who bridge the lives of forest and town. On foot, then on a single motor scooter, Parenti, her husband and two children travel every weekday morning from their forest home to this riverine town, where the youngsters go to school and Parenti serves meals at a small hotel.

In the forest she tends her chacra, a cultivated field where food and medicinal plants grow and chickens run. Parenti's family wants gear like cell phones and other goods of modern life, so she maintains the arduous schedule por la plata, "for the money." Yet she thinks of the forest as home, a place that is "tranquil," where the brutal noise of traffic and loud voices give way to bird calls and, at night, the silence of the rainforest.

As with many Amazon residents interviewed about the synod, Parenti, who is Catholic, said she had not heard of the Vatican gathering. Jorge Luna, a 45 year-old, non-Catholic single father of two who teaches English and Spanish, was likewise unaware of the synod. But he noted: "Any attention from such high levels is a good thing — this is a forgotten place."

Advertisement

But even those well aware of the synod have a hard time following its day-to-day discussions because internet connections in these parts are sketchy, even in this bustling zona fronteriza, a commercial and administrative region shared by outposts of three countries — Leticia, Colombia (pop: 42,000); Tabatinga, Brazil (pop: 62,000), and the island of Santa Rosa, Peru (pop: 2,500). In a twilight conversation at the home of the Capuchin Missionaries, we had to raise our voices to be heard over the clattering din of thousands of jungle parakeets descending upon trees across the street.

People in the central plaza could look up and see the huge sign the Capuchins had installed above this headquarters house: "Laudato Si' Amazonas SOS – Llamados a realizar cambios de estilo de vida, de producción y de consumo" [Called to make changes in style of life, of production and consumption].

Fr. Rodolfo Piñero of Cartagena first came to work in the Amazon in 1992, even before his ordination in 1995. In the last two years, he has participated in some of the hundreds of preparatory synod assemblies across the Amazon where clergy and lay people spoke of their deepest needs and suggested their own solutions, many of which then were reflected in the synod agenda.

Mural on a building along a main street in Leticia, Colombia, reading "La contaminacíon, el paraíso, el futuro está en nuestras manos (Polluion, paradise, the future is in our hands)" (Mary Jo McConahay)

"How to attend to the people without priests?" Piñero asked. "From necessity," he said, "an answer emerged — the 'integration of forces.'" He explained that, in local terms, this means service not according to religious order or country but joint regional work by teams composed of Jesuits, the vicariate, the Capuchin Missionaries, the Hermanas Lauras (the Colombian congregation of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Virgin Mary and St. Catherine of Siena, founded by St. Laura Montoya) and many lay people.

"For the indigenous, there are no borders," Piñero said. Ticuna Indians, for instance, live in Brazil, Colombia and Peru, visiting family or traveling for other reasons without care for seemingly arbitrary national lines. "For them these are not separate places, and we are the same way, a zone of family." For three years the religious team has held meetings and organized encounters while serving the Frontier Zone (50 miles in from each national border) as a single place with many cultures.

The "integration of forces" idea is on the synod agenda. Piñero praised the preparatory synod document, which suggested the possibility of ordaining mature married men, preferably indigenous, and including women in the deaconate. Although considered controversial elsewhere, such ideas hardly raise an eyebrow here. It is "a correct reflection" of the region and its needs, Piñero said.

As Piñero spoke, a middle-aged man called Brother Rebel — that's how everyone refers to him — came in and removed his helmet (motorbikes are the transportation of choice wherever a road exists).

Pastoral function of preserving culture

Formerly a teacher, he showed me pictures from places near Puerto Nariño upriver where he now tends to everyone he meets: backpackers, some drug addicts, members of a host of indigenous communities. He got the moniker, Fray Rebelde, he said, when his superior insisted on assigning him elsewhere; rather than leave the rainforest, he left the Capuchin order.

Twenty years ago, Brother Rebel (Hector Jose Rivera of Cali, Colombia) couldn't stand "the frogs, the food, the heat." Now, he says, he wants to die in the Amazon, so much has its beauty and its people taken him. But things have changed for the worse, he said. He blamed technology — especially television — for stirring desire among young people to have the goods and easy-looking lives they see depicted.

Yet many who desire what the modern world has to offer — like Adriana Parenti, for instance — also seem to yearn to continue as people of the forest, in much the same way as their parents and grandparents. It is a tension that can confuse and even traumatize the young, such as single men and women coming into towns to look for paid work.

Amazon River 59 miles upstream from Tabatinga, Brazil/Leticia, Colombia, June 2002 (Wikimedia Commons/NASA/ISS Expedition 4)

"This is the moment — we must decide how to respond to new times," said Piñero. His order once focused on teaching. Now he aims to gather indigenous in Leticia who want to be with other indigenous in the same living places so they might reinforce common traditions by relating to one another in the midst of an alien culture. It is the pastoral function he feels they must concentrate upon now.

"What is important is presence, and encounter with indigenous." A finca, an extension of rural land, is available so the native youth do not lose "the practice of cultivation." The business of tourism is one way some communities have answered land grabbers, drug dealers or would-be cattle entrepreneurs who destroy the forest in order to create grazing land. The Capuchins' forest reserve might be used for ecological tourism, evangelizing those who come "in terms of Laudato Si', of caring for the Earth, of showing the Creator in all creation," Piniero said.

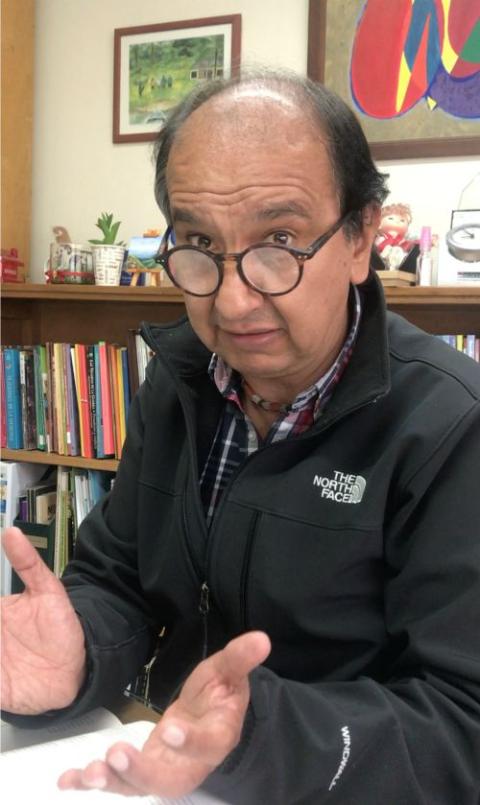

Marco Fidel Vargas, sub-director of the Jesuit research institute CINEP in Bogotá, Colombia (Mary Jo McConahay)

Whatever the church's future in the Amazon, it faces mistrust for sins of the past. Clergy and sisters protected the indigenous from egregious authorities and greedy private businesses, interceding for them. But they did so as parents, another powerful force, not in partnership with the indigenous as equals, according to educator Marco Fidel Vargas, sub-director of the Jesuit research institute CINEP in Bogotá. The church was part of "colonization and a patriarchal past," he said, but now "must enter into a cultural dialogue" with the indigenous.

Before the 1990s, missionaries often brought the brightest young people from the jungle to internados, boarding schools in regional towns, where the students satisfied a thirst for knowledge but were also separated from their traditions, often purposefully. Some of the evangelizers branded customs such as honoring the elements, or honoring animals with whom the indigenous shared the forest, as diabolical. The church was more present than the state in such regions, however, and also ran "contracted" schools.

The 1991 Colombian constitution recognized the right of indigenous to mandate how their children are educated, including in bilingual classes. The number of schools "contracted" by the Colombian government to Catholic religious groups has dropped to about 20%, and since 2000 there are more schools in the territories where the indigenous live, run by church or state. In some places, historically, had there been no church, there would have been no education. Nevertheless, said Vargas. "The church must reflect on this period of its past."

Luis Torres, a Ticuna Indian who administers the social pastoral outreach office at Our Lady of Peace Cathedral in Leticia, Colombia (Mary Jo McConahay)

As the synod draws to a close in Rome this week, meanwhile, the church is reflecting on its future in the region. Will the 185 participants come down on the side of recognizing as deacons women who have been providing long-time service to the church? Will they make the sacraments more available by ordaining married men as priests who can serve remote regions? Or will they reinforce traditional Catholic strictures against such reforms?

Here in the Amazon itself, such debates can take on the feel of quibbling as the Amazon burns.

I asked 26-year-old Luis Torres, a Ticuna Indian who administers the social pastoral office at Our Lady of Peace Cathedral in Leticia, what he expects from the synod.

"The church will never leave its structures," he told me, a hint of resignation, yet also of determination in his voice. "But the Amazon is my Mother Earth. The church here must have an indigenous face. It must dialogue more [with the indigenous], must listen harder."

[Mary Jo McConahay is a longtime contributor to NCR and a prize-winning author, documentary filmmaker and freelance journalist who has reported from two dozen countries over 30 years. Her latest book is The Tango War, The Struggle for the Hearts, Minds and Riches of Latin America during World War II (St. Martin's Press).]