Miraceli de Oliveira reacts as fire approaches her house in an area of the Amazon rainforest near Porto Velho, Brazil, Aug. 16. (CNS/Reuters/Ueslei Marcelino)

One year ago this week, on Oct. 7, the first session of the Synod for the Amazon opened at the Vatican with a prayer service in which bishops, priests, religious and laypeople, including indigenous leaders wearing feather headdresses, filled St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican with song. Over the next three weeks, they discussed issues ranging from the forest fires threatening indigenous territories to ministries for women and the possibility of ordaining married community leaders so Catholics in remote areas could celebrate the Eucharist.

The synod closed with a document that set out a series of pastoral, cultural and environmental challenges for the church in the Amazon. Pope Francis drew on that document in Querida Amazonia ("Beloved Amazonia"), the papal exhortation issued Feb. 12, which resulted from the synod.

Then the coronavirus pandemic swept through South America, battering the Amazon region, with its scattered communities and poor health care facilities. As the wave of illness subsides, the dreams and goals set out at the synod remain, but the church also faces new challenges.

"The pandemic came out of the blue, surprised everybody and here we are," said Fr. Peter Hughes, a Columban priest based in Lima, Peru, who was involved in synod planning and participated as an expert. "Life hasn't been the same and won't be the same."

Vanderlecia Ortega dos Santos embraces her niece outside their home in Manaus, Brazil, May 7. Santos, a nurse, volunteered to provide the only frontline care protecting her indigenous community of 700 families during the COVID-19 pandemic. (CNS/Reuters/Bruno Kelly)

Although the pandemic caught most of the world by surprise, those involved in the synod and Amazonian ministries knew that "the impact was going to be proportionally greater in Amazonia than anywhere else," Hughes told EarthBeat. "And that's exactly what has happened."

The first COVID-19 cases in the Amazon were reported in March, and within a month, hospitals in the region's largest cities — Manaus, Brazil, with a population of about 2 million people and Iquitos, Peru, with about half a million — were overwhelmed. The regional hospital in Iquitos ran out of oxygen for patients.

In urban areas, people who work for day wages or in the informal economy found themselves unemployed — and increasingly hungry — as countries locked down. In more remote areas, indigenous communities closed themselves off, a strategy their ancestors also used to ride out epidemics. But as the lockdowns dragged on for months and relatives sought to return from cities to their home communities, the virus spread up and down the region's rivers.

For Bishop David Martínez de Aguirre Guinea of Puerto Maldonado, Peru, who hosted Pope Francis during his 2019 visit to the Peruvian Amazon and was a special secretary at last year's synod, the pandemic has been a time of both crisis and grace.

After hearing synod participants describe the lack of public services like health care and education in their communities, as well as the violence they faced, "Pope Francis said, 'We have heard the cry of the Amazon,' " Martínez told EarthBeat.

"The pandemic has made that even more clear. But we have also seen the resilience of the people, and the ability of communities to respond to whatever comes their way. It has not only laid bare tragedy. It also has revealed grace and the people's ability to respond and take action."

At the Iquitos hospital, patients lay on corridor floors or sat in reception areas, breathing through masks attached to oxygen tanks, until the demand for oxygen outstripped the supply. With patients dying for lack of oxygen, Augustinian Fr. Miguel Fuertes, administrator of the Iquitos Vicariate, launched an online emergency appeal on May 3 for $120,000 to buy oxygen-generating plants for the local hospitals.

Advertisement

By the next evening, people had donated nearly $500,000, enough to buy the plants, as well as medicine and equipment for health centers in remote communities. Other church jurisdictions in Peru followed suit, filling in for a government whose unwieldy bureaucracy failed to keep pace with the rapid spread of the virus.

And throughout the Amazon, the church provided food and medical care, accompanied the grieving and helped bury the dead.

The Red Eclesial Panamazónica (Pan-Amazonian Ecclesial Network), which was founded in 2014 to increase coordination among church workers in the region, began tracking COVID-19 cases and deaths throughout the Amazon, using official health ministry figures.

By Oct. 8, the nine countries that share the basin had reported more than 1.27 million COVID-19 cases in the Amazon region and more than 32,000 deaths, although officials say the real figures are probably far higher.

REPAM has also worked with the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin, an umbrella group of Amazonian indigenous groups, to track cases and deaths among indigenous peoples. As of Oct. 6, they had reported nearly 2,000 deaths.

The loss of indigenous community chiefs, shamans and other elders, both men and women, will have a lasting impact, said José Gregorio Díaz Mirabal, the umbrella group's coordinator general, who participated in the synod.

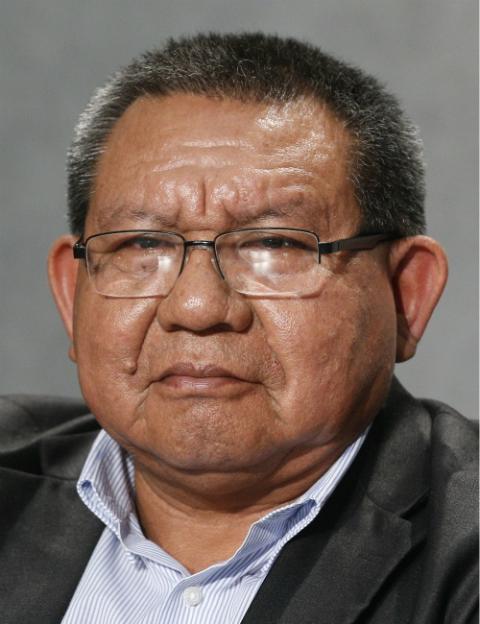

Pope Francis meets José Gregorio Díaz Mirabal, a member of the Curripaco indigenous community, during a session of the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon at the Vatican Oct. 8, 2019. (CNS/Vatican Media)

"For us, it [has been] something so hard, so difficult, that it will be impossible to recover," he said, adding that those deaths represent the loss of "thousands and thousands of years of knowledge, of our culture."

The pandemic also brought about abrupt changes in the way the church operates, said Salesian Fr. Justino Sarmento Rezende of Santa Isabel do Rio Negro, in Brazil's Amazonas state.

"The pandemic changed the church's ecclesial routine. Everything was affected. Meetings and weekly gatherings were canceled, celebrations postponed," said Rezende, who participated in the synod as an expert.

"We were not prepared for social isolation," he said, adding that Catholics have had to learn a new way of being church.

Fr. Justino Sarmento Rezende attends a news conference to discuss the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon at the Vatican Oct. 17, 2019. (CNS/Paul Haring)

"We had to review everything from catechism vows to Masses, burials. We had to think of a domestic church, where the family is the core of the church," he said. "The pandemic forced families to really assume Christian practices inside their homes. The pandemic showed that the church is much more attached to the physical church, to the building itself, than it needs to be."

The pandemic also revitalized the use of traditional cures in indigenous communities, said Rezende, who is Tuyuka and the first indigenous person to be ordained a priest in Brazil. Without access to Western health care, villagers depended on traditional knowledge of healing with plants — unfamiliar to younger indigenous people, he said.

Despite the pandemic, cross-border coordination among bishops continued, Martínez said.

The Ecclesial Conference of the Amazon, a coordinating group created in June, held its first assembly virtually in September and will hold another later this month. The group consists of bishops, religious and laypeople, but how it will operate and relate to other Latin American church structures is still being worked out, Martínez said.

Over the next few months, the Pan-Amazonian Ecclesial Network will conduct an evaluation of its six years of existence, said Marist Br. João Gutemberg Sampaio, who was an observer at the synod and who became executive secretary of the network in September, replacing Mauricio López, who had led the group since it was created.

Within countries, the pandemic halted or drastically changed post-synod activities.

"We returned [from Rome] with many plans for the post-synod process," said Márcia Maria de Oliveira, a social sciences professor at the Federal University of Roraima in Boa Vista, Brazil, who participated in the synod as an expert.

The idea was to begin by encouraging communities to study the synod's final document, followed by Querida Amazonia, and hold regional assemblies like those organized in preparation for the synod, to help communities understand the conclusions and draw up pastoral plans.

Pope Francis attends a prayer service at the start of the first session Synod of Bishops for the Amazon at the Vatican Oct. 7, 2019. (CNS/Vatican Media)

Some of those meetings, including regional assemblies, have been held virtually, and although that is not the same as meeting in person, the process is advancing, though more slowly than originally planned, she said.

About 60 women from throughout the Amazon have also been meeting monthly via the internet, she said. Greater recognition of women's ministries, including opening the diaconate to women, came up for discussion in the synod, but the pope did not include that in Querida Amazonia and the issue is still under consideration.

Widespread use of the internet has created new challenges for church workers who aid victims of human trafficking in the Amazon region, said Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Roselei Bertoldo, who was an observer at the synod. Sex work has gone online, and traffickers recruit their victims using cellphone apps.

She told of a young Venezuelan man, a migrant in Manaus, who was lured to a house with a promise of a modeling photo shoot, but ended up held against his will for several days engaging in "virtual sex" before he managed to escape.

The pandemic has also increased the urgency of other issues that were discussed extensively at the synod, especially the destruction of forests and threats against indigenous peoples. Deforestation and fires have accelerated this year, as law enforcement efforts have been hampered by the pandemic and communities have been less able to mobilize to defend their lands.

Yanomami are seen in a file photo following members of Brazil's environmental agency during an operation against illegal gold mining on indigenous land in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. (CNS/Reuters/Bruno Kelly)

The pandemic has also spurred a gold rush, in which illegal miners often invade indigenous territories. In Brazil, that is part of a pattern of accelerating land invasions, conflict and violence that has worsened since President Jair Bolsonaro took office in January 2019, according to a September report by the Brazilian Catholic Church's Indigenous Missionary Council. Nearly 1,200 indigenous people have been killed in such conflicts since 1985, according to the report.

Land conflicts also affect small farmers who lack official title to their land. Many have been forced from their homes by court order or hired gunmen, says Josep Iborra Plans, of the Brazilian bishops' Land Pastoral Commission.

The evictions, which are often spurred by land speculators, leave the families without shelter or an income, making them even more vulnerable to COVID-19.

"How can you stay at home, protecting yourself from the coronavirus, if the judge, the police or the gunslinger throws you and your family out of your home and farm?" Plans said.

Patricia Gualinga speaks at a news conference to discuss the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon at the Vatican Oct. 17, 2019. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Indigenous leaders went to the synod in the hope that the pope, as an international leader, would draw attention to the threats they face in the Amazon.

"I think the synod has had an impact in the region," said Patricia Gualinga, a Kichwa leader from Sarayaku, Ecuador, who was an observer at the synod. "Although sometimes people try to focus on whether or not there will be married priests, for us it was very clear that the central issue was care for creation, solidarity and the protection of indigenous peoples."

Increasingly, church leaders are speaking out and issuing statements in defense of the Amazon and indigenous territories, said Gualinga, who is a lay member of the new Ecclesial Conference of the Amazon.

"It may not be enough, because the governments don't want to pay attention," she added, "but [government leaders] know there is a document, there is a church network, there are guidelines to help protect the Amazon as a place that is alive and vital for humanity, a place that cannot be lost, because it is humans who would lose."

[Barbara Fraser is editor of EarthBeat. Contact her at bfraser@ncronline.org. Lise Alves, a freelance journalist based in São Paulo, contributed to this story.]