The remains of virgin Amazon rainforest are seen after it was cleared for its wood along a highway near a town in Moju, Brazil, May 26, 2012. (CNS/Reuters/Lunae Parracho)

Much of the attention at December's United Nations biodiversity summit focused on what governments must do to reverse decades of ecosystem destruction. But the role of preserving nature is not limited to nations.

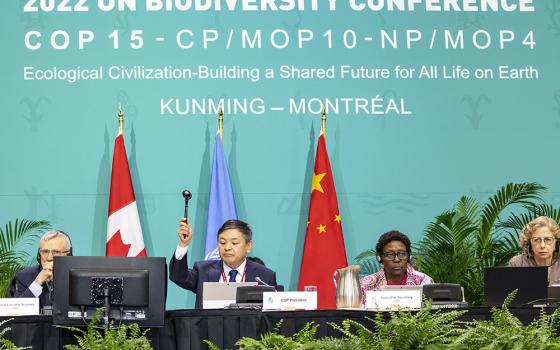

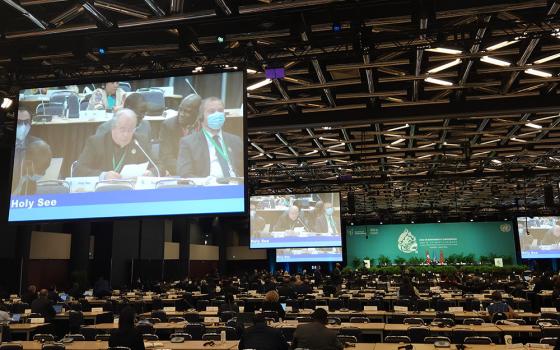

During the two-week COP15 summit in Montreal, two new guides were issued to support faith communities who want to join larger efforts to protect the world's ecosystems through reforesting and facilitating conversations around environmental restoration.

Globally, religious communities oversee 8% of habitable land and 5% of commercial forests, according to the U.N. Environment Programme's Faith for Earth Initiative. And roughly 8 in 10 people worldwide associate with a religious tradition. Together, those statistics outline the outsized role that people of faith could play in restoring and revitalizing ecosystems, said Fran Price, global forests lead for World Wide Fund for Nature, or WWF International.

Just as important as influence and land holdings, she said faith-based groups bring "tradition and a set of values that includes stewardship and respect for the intrinsic value of nature."

During COP15, WWF International, along with UNEP and the Trillion Trees project, debuted a guide on growing trees sustainably, specifically for faith groups.

Andrew Schwartz, director of sustainability and global affairs for the Center for Earth Ethics, speaks during a panel discussion on how values, culture and spirituality relate to ecosystem restoration Dec. 13 at the COP15 United Nations biodiversity conference in Montreal. Also pictured, from left, Lauren Van Ham, climate action coordinator for United Religions Initiative; Karenna Gore, founder and director of the Center for Earth Ethics; Dianne Klaimi, program management officer at the U.N. Environment Programme; and Oscar Soria, campaign director for Avaaz. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

The guide, available in 10 languages, outlines six steps to help religious communities go from thinking about planting trees to stewarding them as they grow.

"Faith-based organizations and actors are uniquely placed to undertake meaningful and sustainable tree growing initiatives across a variety of landscapes, carrying with them huge potential to utilize existing infrastructure, networks, human capacity and dedication necessary to successfully contribute to forest restoration," the guide states.

Forests are critical ecosystems for the planet, covering almost one-third of Earth's land, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization's 2020 "The State of the World's Forests" report. They are home to most land-based biodiversity, and provide resources for food, energy, medicine, shelter and income.

And forests play a critical role in limiting climate change, acting as "carbon sinks" that absorb carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas emitted from burning fossil fuels — from the air and convert it to biomass and store it in soil.

The FAO trees report found that while the pace of deforestation has decreased in the past three decades, forest loss totaled 10 million hectares per year between 2015 and 2020, and more than 80 million hectares of primary forest — naturally regenerating and free of logging — have been lost since 1990. A main driver has been converting land for agricultural purposes.

Advertisement

In recent years, faith-based organizations have been active in reforestation and forest protection efforts, such as supporting the Great Green Wall Initiative in Africa's Sahel region. Since 2017, the Interfaith Rainforest Initiative has advocated to end tropical deforestation and focused its work in five countries — Brazil, Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia and Peru — that together are home to 70% of the remaining tropical forests.

The new guide looks to engage more faith communities in tree growing in their communities. It makes a distinction between tree planting and tree growing, with the latter emphasizing long-term care for trees as they grow. Price told EarthBeat that the high rate of failure in tree projects often results "because that tree-growing element was not included from the get-go."

"It's really about seeing a whole process through and stewarding those trees," she said.

The guide applies to tree-growing efforts both big and small, whether a commemorative tree at a place of worship, a community project to increase green space in a city, or a larger-scale project like planting a sacred forest.

The first step the guide advises is to define the purpose of the tree-growing initiative. Is it to create a place for prayer and spiritual reflection? Or provide food or shade for the community? Or to protect local threatened species?

Trees reflect in a pond along a trail in Acadia National Park in Bar Harbor, Maine. With scientists warning that the loss of nature is accelerating at dangerous speeds, Catholic activists urged nations at the U.N. Biodiversity Conference in Montreal to act to protect life on earth at all levels. (CNS/Bob Roller)

From there, the guide suggests exploring what partnerships may exist for collaboration and outreach, placing special emphasis on adopting a rights-based approach that asks questions about the land where the trees will be planted and who has access, control or cultural ties to it.

The guide also offers assistance for selecting the right trees for a region, the right time and place to plant them, and how to continue to care for them as they grow. WWF International is planning to host workshops to provide further assistance.

The guide is part of efforts around the U.N. Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, an effort to accelerate efforts through 2030 to halt and reverse environmental destruction worldwide. During COP15, 10 flagship programs were announced — including growing Africa's Great Green Wall and rejuvenating India's holy Ganges River — and U.N. agencies are looking at ways faith communities can play a role in those projects.

A second guide issued at COP15 and directed at faith communities also looks to support conservation efforts around the U.N. Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. The "Ecosystems Restoration Conversation Guide" was created by the Center for Earth Ethics in partnership with the United Religions Initiative. Its purpose is to help faith communities initiate and facilitate dialogues about what restoring ecosystems would mean where they live.

"There's so much potential to reconnect in faith communities to bodies of water, to places where food can be grown, to forests," said Karenna Gore, founder and executive director of the Center for Earth Ethics, which formed in 2015 at Union Theological Seminary in New York City.

Renowned conservationist and primatologist Jane Goodall delivers a video message during the launch of 10 flagship conservation projects as part of the United Nations Decade of Ecosystem Restoration on Dec. 13 at the COP15 biodiversity conference in Montreal. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Gore and staff with the Center for Earth Ethics presented the 12-page guidebook in Montreal at the faith pavilion. She told EarthBeat that it's designed to be a "catalyst" for faith groups to begin asking questions about what environmental damage exists in their communities and regions, how it happened, and what role they can play in reversing it.

"This is an invitation to practically look at what's going on in your world, to see who's working on it, and figure out how you can help," said Andrew Schwartz, director of sustainability and global affairs for the center, who added that houses of worship can become "an incredible home base" for those already ongoing efforts.

In developing the guidebook, the Center for Earth Ethics held a series of consultations to model the types of conversations it envisions around ecosystem restoration, ones inclusive of people of faith, Indigenous groups, local government, U.N. agencies and advocacy organizations.

The first such conversation took place in St. James Parish in Louisiana, where community groups, many of them with religious roots, formed in response to petrochemical complexes proposed in the region known as "Cancer Alley."

"In St. James Parish, they want restoration, but right now they're just resisting," Schwartz said. "They're saying no to these petrochemical plants. They're advocating for themselves, for their health, for their community, for the environment."

A member of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation is seen in a deforested area in the Bom Futuro National Forest Sept. 13, 2019, in Rio Pardo, Brazil. (CNS/Reuters/Bruno Kelly)

Other consultations took place in the Philippines, where the Bagobo Tagabawa's "forest guardians" are striving to protect the endangered Philippine eagle, and in India, where Hindus are striving to clean up and reconnect spiritually with the heavily polluted Yamuna River.

"It would be really a very stilted and incomplete conversation if one didn't take into account the spiritual and cultural traditions that people have had in connection with that river. And the development model doesn't take those things into account usually," Schwartz said.

But the restoration guidebook isn't only about revitalizing degrading environments, added Gore, who sees it also as a way for people of faith to recognize themselves as part of nature and its restoration as a spiritual act.

"The most important thing to restore is the relationship of human beings to their ecosystems," she said.