An irrigation system is seen along rows of crops at the family farm of Rony Figueroa in Central Honduras, in a region known as the Dry Corridor. Figueroa twice migrated when it seemed impossible to build a secure life for his family in Honduras. After returning and receiving support from organizations including Catholic Relief Services to adapt farming techniques to climate change impacts, Figueroa has been able to stay and call Honduras home. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

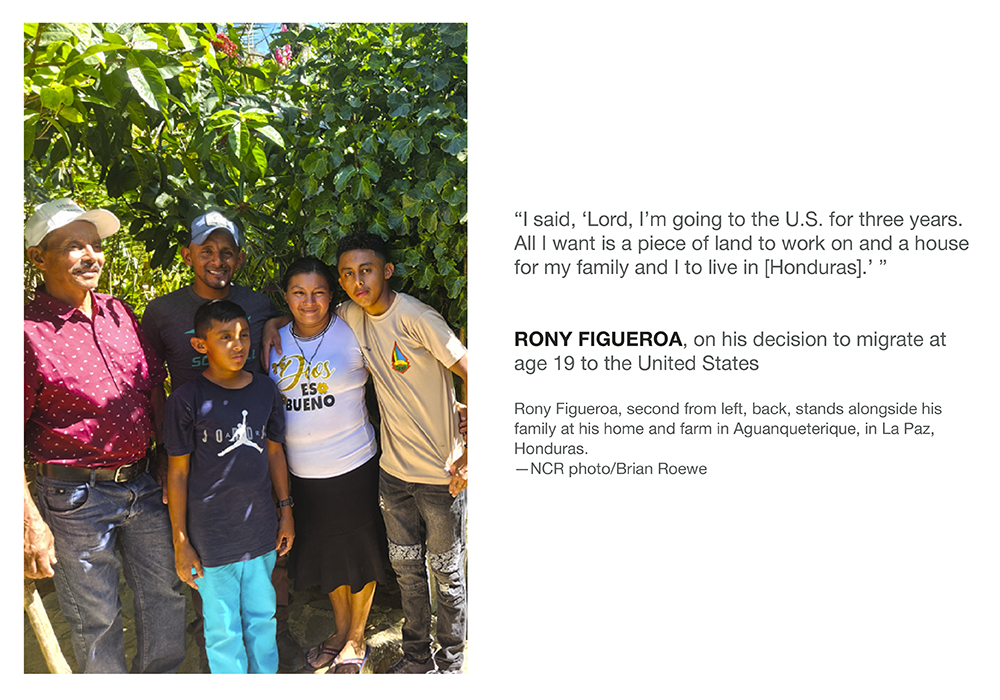

Deep in a remote, brown-tinged valley between palm tree-dotted hills is a soccer field at the family farm of Rony Figueroa.

It's the same field where Figueroa grew up playing the sport with friends every afternoon. As he got older, he'd join matches with his dad and other adults. When Figueroa bought the property from his father, he worked with the local municipality to improve the playing surface.

During a visit in late March, the field lay empty, in what would normally be an active time on the pitch ahead of the rainy season that historically arrives in May in central Honduras. At least that was the case a decade ago, but not in recent years.

"It makes me really sad to see a very pretty soccer field and there's not a lot of young people playing," Figueroa said on a sweltering, clear-skied day.

Part of the reason for the lack of soccer players is fewer young people living in the small town of Aguanqueterique in the heart of Honduras' Dry Corridor. More are migrating north to larger cities or taking the longer arduous journey to the United States, driven by a lack of jobs and opportunities in their homeland. The region is widely dependent on agriculture, with many families growing their own food. As rainfall patterns have become less consistent and periods of drought have persisted, harvests have dried up, and with them, prospects to build a better life.

"You need clothes, you need food and all of that. There's no employment sources, so people migrate," Figueroa said.

He can relate to the difficult dilemma facing Honduras' youth. He once left his home to head to the U.S., too.

But ultimately, Figueroa returned, and with support from local groups, international nongovernmental organizations and development agencies, including Catholic Relief Services, has built a life for his family as a farmer in his homeland.

In Honduras, the impacts of climate change are inseparably woven into the complexities of migration, on vivid display in the small and remote villages spread out in the Dry Corridor — a region of central and western Honduras whose name hints at the trials of farming in an area where water access is often scarce. (The Dry Corridor extends into other countries in Central America.) Though not the lone factor driving migration, the impacts of global warming are exacerbating the agricultural and economic strains that lead people to leave.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

As industrialized countries like the U.S. concentrate climate responses on mitigation, Honduras is squarely on the front lines of climate adaptation, where the impacts of more than a century of burning fossil fuels around the world are widely evident. Efforts here, where half the population lives in poverty, focus on building resiliency and learning to live with the changes wrought by a rapidly heating world. Many endure a daily fight to survive that begins with a basic need for water. When adapting isn't possible, some look to leave, with ramifications for the countries where they head as well as for the communities they leave behind.

"[Water] is what they need to feed their families and it's what they need to have a life in Honduras," said Haydee Díaz, country representative for Catholic Relief Services Honduras. "One thing that farmers will sometimes say is, 'If I have water, I have a crop to harvest. And if I have a crop to harvest, then I can stay here.' "

In Dry Corridor, problems start with water

Across the community of Los Hornos — "The Ovens," in Spanish — in a blistering, arid part of the Dry Corridor near the border of El Salvador, the dry season and lengthy droughts have painted the tropical landscape in shades of sepia and pale yellow among strewn patches of green canopy.

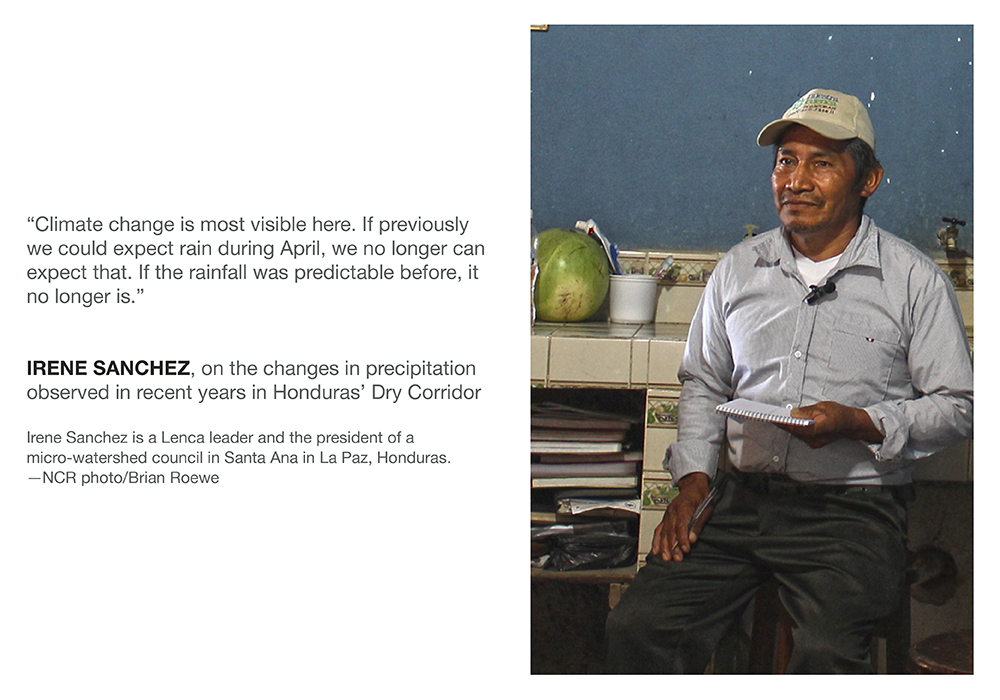

The communities, mostly Indigenous Lenca, used to rely on a rainy season beginning in April, but rainfall has become less predictable and now often doesn't arrive until May. At times, the precipitation comes in short dramatic spurts, dropping levels that used to fall over several months in a day, or even in a few hours. Most people here are subsistence farmers, growing beans and corn for their own food. Few have irrigation systems, so they're dependent on what, and when, nature provides.

Los Hornos — "The Ovens," in Spanish — is a blistering, arid part of the Dry Corridor near the border of El Salvador. Communities there, mostly Indigenous Lenca, used to rely on a rainy season beginning in April, but rainfall has become less predictable and now often doesn't arrive until May. Most people here are subsistence farmers. Few have irrigation systems, so they're dependent on what, and when, nature provides. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

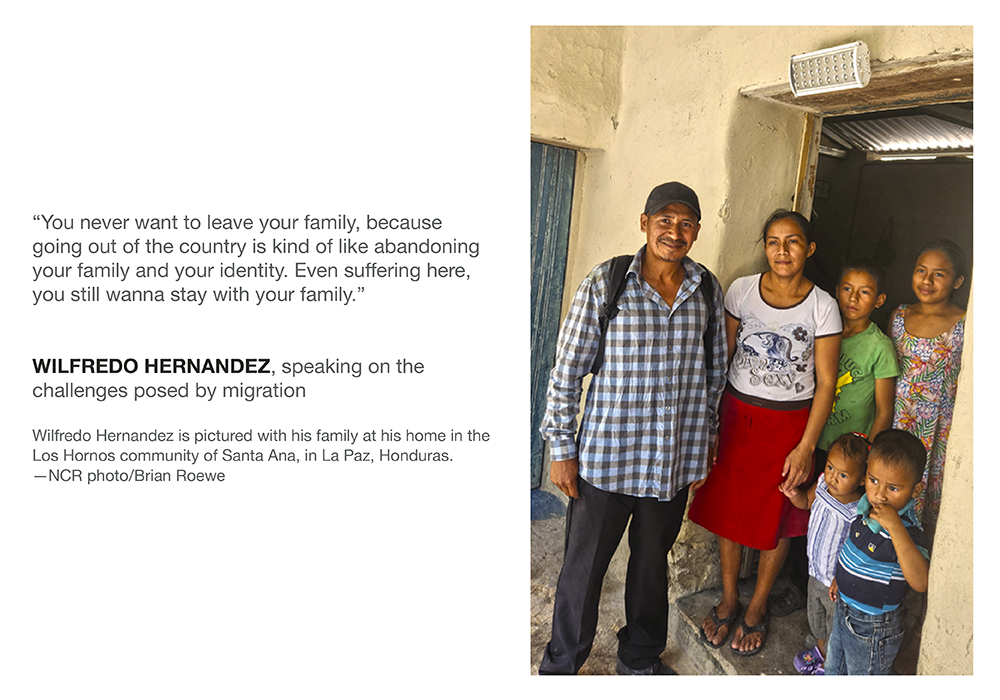

Limited water access has led Wilfredo Hernandez to plant a smaller corn variety that requires less water on his plot of land several hours down an unpaved road outside the town of Santa Ana.

"You never know the type of change we're going to have, but you always try to produce something," he said.

In the heart of Central America and home to 10.4 million people, an estimated 34%-38% of whom are Catholic, Honduras is among the world's most vulnerable countries to climate change. Roughly the size of Louisiana, it ranked from 1993 to 2012 as one of the three countries most affected by extreme weather events, according to the Global Climate Risk Index published by the environment and human rights organization Germanwatch.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Through working more than six decades with communities in Honduras, the staff of Catholic Relief Services, or CRS, have observed how increasing temperatures have made hard lives even harder. In the Dry Corridor, the problems start with water: Too little rain and crops dry up; too much at once and planted fields are wiped out.

"Climate change has a huge impact because the watersheds are always drying up," said Miguel Flores, a senior technical adviser for CRS Honduras who has worked nearly 40 years on sanitation and Water-Smart Agriculture initiatives in the country.

Naturally occurring weather phenomena, like tropical storms and El Niño, have long been challenges for countries across Central America's Dry Corridor. In both cases, climate change is intensifying the impacts.

Honduras' geographic location exposes it to El Niño — the recurring cycle of warmer waters in the Pacific Ocean that triggers increased rainfall in some parts of the world and amplifies heatwaves in others, as seen this summer. As El Niño raises temperatures, droughts in Honduras have become more extreme. The worst years saw farmers losing nearly all of their crops. In 2018-19, a weaker El Niño still brought devastation as a severe drought wiped out upward of 80% of crops for 65,000 farmers the first year, and in the second 170,000 farmers lost more than half their fields, according to Catholic Relief Services.

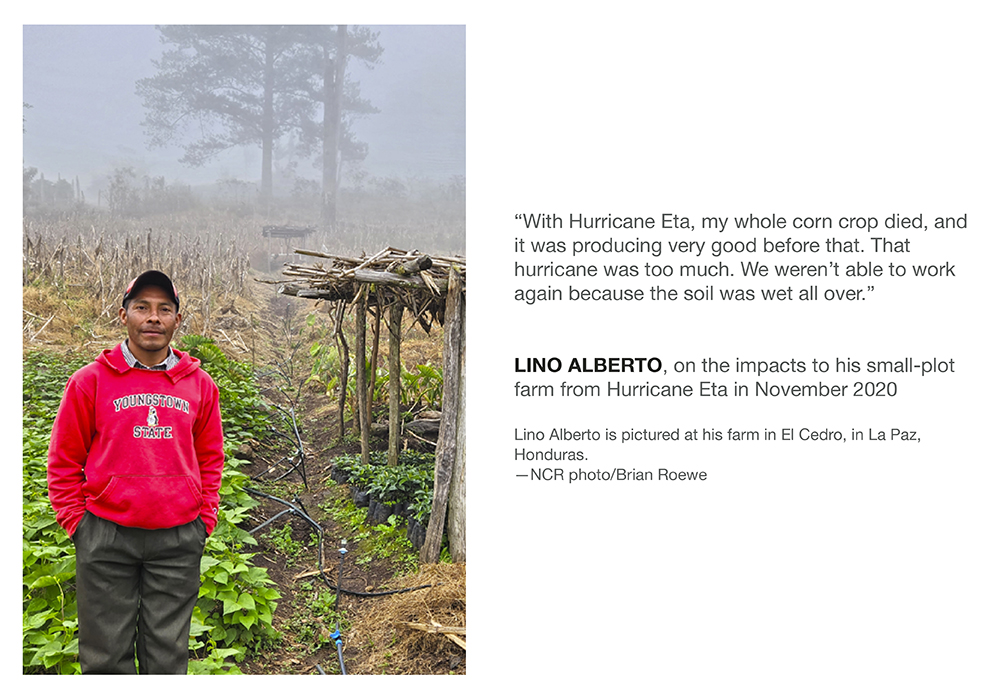

Crop loss has also followed major tropical storms, as was the case in November 2020, when twin Category 4 hurricanes, Eta and Iota, struck Honduras days apart. While the hurricanes made landfall along the northeast coast, torrential rainfall carried well into the Dry Corridor.

In the mountainous El Cedro community, floodwaters swamped the fields of Lino Alberto, wiping out his entire corn crop, food he relies upon to feed his family.

"It was producing very good before that," he told EarthBeat, pointing to his land. "That hurricane was too much. We weren't able to work again because the soil was wet all over."

While powerful storms are not increasing in frequency, they are intensifying faster with climate change as warmer ocean water provides fuel for stronger storms, said Josue Mejia, a meteorological specialist at the Honduran Institute of Earth Sciences at National Autonomous University of Honduras, in the capital city of Tegucigalpa. Eta transformed from a tropical storm to a Category 4 hurricane in roughly 24 hours, while Iota did the same in about 32.

"The impacts of climate change are hitting us," he said.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

The institute is one of a number of local organizations with which Catholic Relief Services has partnered during its 60 years in the country. In the past decade, they've focused attention on assisting subsistence farmers to adapt to challenges brought by climate change. That has included studying how it affects the country and how to equip small-scale producers with agricultural tools and techniques to weather the impacts.

"It's so important for producers to have enough safety to know that what they plant will actually produce something instead of generating losses. And the only way to ensure that is through water," Flores said.

Water is critical not just for the fields, but for the communities themselves, he added. For food security, for consumption, for health and hygiene. "Water issues cannot be separated from life," said the civil engineer who has helped establish 750-plus potable water systems across rural Honduras.

A view of a landscape within the Dry Corridor in La Paz, Honduras, in late March. The Dry Corridor is a region of central and western Honduras whose name hints at the trials of farming in an area where water access is often scarce. The Dry Corridor also extends into other countries in Central America. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Historically, Honduras has had two seasons: the dry summer, from November to April, and winter, or the wet season, from May to October, with a brief break in July and August. In the past, farmers would plant first in April and again in September. Too short a rainy season or too little rainfall won't allow the crops to bloom and results in food and economic losses.

"If the rainfall was predictable before, it no longer is," said Irene Sanchez, a Lenca leader and president of a micro-watershed council working to protect water access in La Paz.

In analyzing data from the country's roughly 400 meteorological stations, the Honduran Institute of Earth Sciences found little change in total annual rainfall from 1980-2010, said Max Ayolo, a hydrology specialist at the institute. Instead, they discovered the rain falling more in areas that already saw high precipitation and less in historically dry parts.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

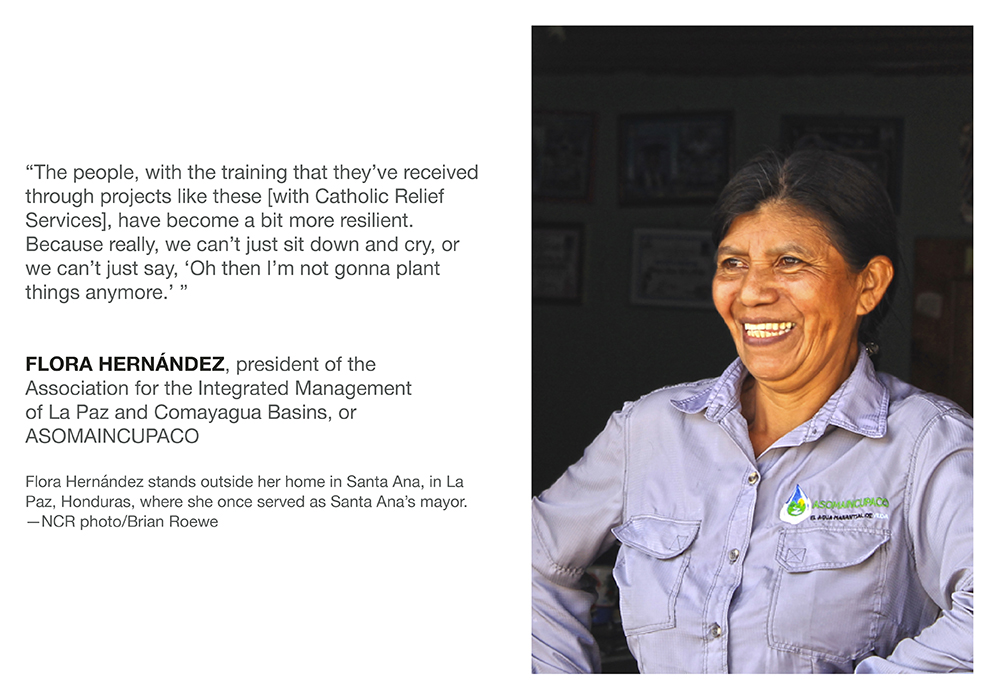

In Los Hornos, the local water board helps allocate water to 37 families. It is one of nearly 50 watersheds established by the Association for the Integrated Management of La Paz and Comayagua Basins, or ASOMAINCUPACO, a nonprofit organization of 42 communities that has worked closely with Catholic Relief Services in the region.

While water is the major challenge climate change has posed here, it's not the only one. Changing weather conditions have allowed invasive pests, like the pine weevil and bark beetle, and fungi like coffee rust to spread and wipe out coffee and bean crops as well as thin out pine forests, which are critical for water retention.

"Those are all consequences from the bigger countries who produce the greenhouse gasses. … And then we, the [small and underdeveloped] countries are the ones who have to pay," said Flora Hernández, president of the association and a Lenca leader.

A field of bean crops at the family farm of Wilfredo Hernandez, several hours down an unpaved road outside the town of Santa Ana, La Paz, in Honduras. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Despite the hardships that climate change creates, farmers here remain determined, reassured by their Indigenous past of finding ways to survive on the land.

"We want to progress, we want to lift ourselves up," Sanchez said of a region that strives to become world-class producers of corn and coffee, the latter Honduras' largest export as a top-five global coffee producer. But to get there, he said, they need outside assistance to become self-sustainable and more resilient to a changing climate.

The Association for the Integrated Management of La Paz and Comayagua Basins, which receives funding from CRS and other international organizations, has worked to improve and adjust agricultural practices, from irrigation systems to soil management, including diversifying crops, to ceasing "slash-and-burn" techniques that clear forested land for agriculture.

"Nature is just giving us an invoice after everything that we've done to it. So we have to learn how to survive all of this," Hernández said.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Migration is 'a family problem'

The challenges that climate change adds to already difficult growing conditions compound harsh living conditions in much of Honduras, one of the most economically poor countries in the world.

According to The World Bank, 52% of Hondurans were below the poverty rate as of 2022, with 13.3% facing extreme poverty, slight decreases from 2020 when the twin hurricanes and COVID-19 pandemic battered the country, particularly rural areas. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification estimates that 2.3 million people currently face high levels of food insecurity — attributed to high prices, weather-related disasters and sharp declines in basic grains production from difficult growing conditions — and the country was named a "hunger hotspot" in 2022 by international food organizations. As of 2021, 700,000 Hondurans were living in the U.S. while that same year the U.S. Department of Homeland Security reported 331,397 apprehensions of Hondurans both at the border and throughout the country.

Unemployment, high living costs and insecurity are the biggest concerns facing Hondurans, per a September 2022 Gallup survey that also found 71% of respondents said it was somewhat or very likely they would leave the country in search of better opportunities if they had the resources to do so.

An asylum-seeking migrant from Honduras holds his 2-year-old son as he awaits to surrender to border agents after being smuggled across the Rio Grande river from Mexico into Roma, Texas, Nov. 18, 2022. (CNS/Reuters/Adrees Latif)

At one time that included Figueroa.

A year married with a 3-month-old son at age 19 in 2006, he was working multiple jobs to save money to move out of his father's home when he received a call from the U.S. A relative living there suggested Figueroa join him, with the promise of "big bucks" — five to six times more than his daily wages. Within 24 hours, he made the decision to leave.

"I said, 'Lord, I'm going to the U.S. for three years. All I want is a piece of land to work on and a house for my family and I to live in [Honduras],' " Figueroa recalled.

The journey north was dangerous. He knew friends who had died or been injured along the way. He traveled with a cousin, who knew the route to the border. While in Mexico City, Figueroa begged for food and was chased by immigration police. He crossed the border illegally in Arizona, and eventually landed in New York City.

He worked various jobs, logging 14 to 15 hours a day while earning $900 to $1,000 per week, enough not only to save for his future home but also to provide with one day's wages two weeks' worth of food for his family.

Advertisement

In 2010, while working for a sewage line company in Indiana, he and his cousin were stopped by police at a supermarket and turned over to the migration bureau, who gave them a choice to plead their case in court and risk jail time or agree to be deported. They chose deportation.

Back in Honduras, Figueroa built a home, but with little money left afterward he migrated again, this time to work on houses in Tegucigalpa. While fixing a roof one day, he was electrocuted by a live wire, fell two stories on his back and "almost met the Lord." Unconscious and near death, he asked for God's forgiveness and promised to return to his family if his life was saved. When he recovered, he went home for good.

Figueroa's time away was difficult for his family, too. "I was the one who did everything here," his wife Reina said, including caring for their newborn son, tending to the house and working while Rony looked for a job in the U.S. At times, she felt afraid and worried of break-ins.

When she was able to send word to Rony, she urged him to come back. When he finally did, she asked that he not leave again.

Towns across La Paz are filled with stories of others who've migrated.

Nora Lizeth Valdez twice attempted to enter the U.S. Upon being sent back to Honduras, she received training through ASOMAINCUPACO and Catholic Relief Services to become a veterinarian technician. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

For Nora Lizeth Valdez, 37, of Aguanqueterique, her two attempts to enter the U.S. in 2019 left her and her 10-year-old daughter at one point kidnapped by a Mexican gang. Also motivated to provide a home for her and her two daughters, Valdez, upon being sent back to Honduras, has received training through ASOMAINCUPACO and Catholic Relief Services to become a veterinarian technician, the first woman in her municipality to hold the position.

Both Walter Mauricio Hernandez, 20, and Marcus Rufino Castillo Diaz, 21, have family members who left their homes in San Antonio to head to the U.S. But they have remained, spending their mornings in the fields growing basic grains for their families. Afterward, they used to work on nearby farms for 150 lempira a day, but now they earn additional income for their families as beekeepers through a CRS program.

"It's very common to migrate here," Hernandez said. "Almost every young person thinks about that, or they do leave."

In many of the communities where CRS works, young people "are almost nonexistent," Flores said.

Fr. Luis Melquiades, a 33-year-old priest, sits inside St. Anthony of Padua Church in Mercedes de Oriente, Honduras. When Melquiades was 14, his father left for the U.S. and returned 16 or 17 years later. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

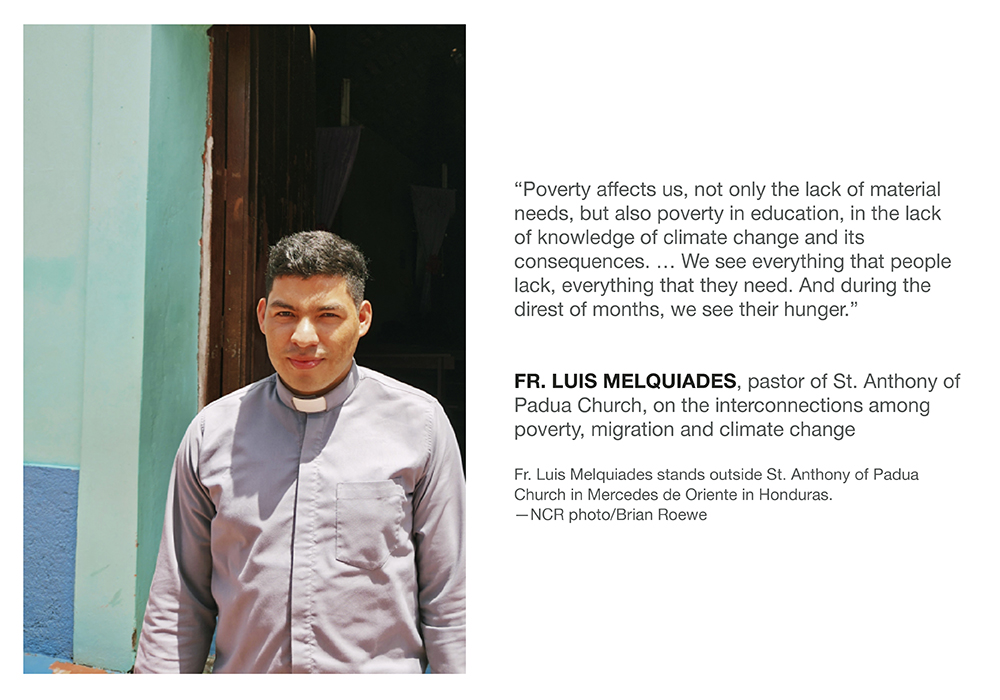

At St. Anthony of Padua Church, in Mercedes de Oriente, a town of 1,200 people in southwestern Honduras, the Catholic parish works to accompany the families who are left behind, mostly older people and women.

"People get disillusioned," said Fr. Luis Melquiades. "The farmer who plants says, 'I just don't want to plant things anymore because it's no good to me.' The young person says, 'There's just no way to live here.' "

The 33-year-old priest knows the impact of a family member's departure. His father left for the U.S. when Melquiades was 14 years old. When he returned 16 or 17 years later, it was difficult for the family to form relationships with a father they never knew.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Gabriela Morales, a member of the Fe y Esperanza neighborhood group, called migration "a family problem." While many head north with the goal of providing for their families back home, it places strains on family ties, she said. Parents divorce. Kids leave. There's remarriages and new families. When both parents migrate, children are raised by grandparents. Even the economic benefits can breed problems, as families can become dependent on remittance payments and are less motivated to work, or turn to illegal activities when payments dry up.

"The family suffers," Morales said.

The lack of young people also means less "young muscle to work," said Concepcion Velasquez, a Lenca elder and president of Fe y Esperanza. With fewer able producers, families are limited in what they can grow, even under optimal conditions, and opportunities for development — such as infrastructure projects to capture and distribute water — also diminish, allowing poverty to stagnate and continuing cycles of migration.

"We know the person doesn't go just because they want to, but because of the lack of employment," Morales said. "Our families, our young people want to get ahead."

Members of the Fe y Esperanza neighborhood group, including Gabriela Morales (second from right) are seen seated during a meeting with the deputy mayor (not pictured) and Fr. Luis Melquiades (far left). Morales called migration "a family problem." (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Climate adaptation tools, training bear fruit

At the end of a long and winding rock-strewn road, a new bridge is under construction connecting the primitive path to the Los Hornos farming community on the other side of a creek. The nearly 40 families who call this remote part of La Paz home are happy to share and show off the fruits of their labor. There are the staples of corn and beans, but also radishes, watermelon, taro, yuca, pineapple, plantains, cucumbers, tomatoes, green beans, rice and ginger.

The colorful and flavorful cornucopia are the bounty cultivated and grown partly through a series of irrigation systems the community built with the help of Catholic Relief Services, the Association for the Integrated Management of La Paz and Comayagua Basins, and other local partners.

The community draws water for their fields from the creek, a necessity, said Desiderio Vasquez, a local farmer, as climate change has lessened rainfall. They irrigate crops like corn and green beans, whose yields have become enough that they're able to sell surplus at market, along with tomatoes, radishes and sorghum. They're also in the process of trying to sell rice, using a variety that requires less water.

Desiderio Vasquez, a local farmer, shows off a colorful cornucopia of the bounty cultivated and grown partly through a series of irrigation systems the community of Los Hornos built with the help of Catholic Relief Services, ASOMAINCUPACO and other local partners. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

The scene is a far cry from the one when Catholic Relief Services first arrived in 2015, when less accessible roads led staff for miles on foot to reach the community center. At their first meeting, CRS asked the community to organize and together identify projects that would improve their lives. After some initial hesitation, they agreed. Their first priority: potable water, followed by repairing their homes. CRS provided training on potable water and funding for home construction projects, which the community carried out themselves.

Fresh corn offered to visitors by the community of nearly 40 families in Los Hornos. When Catholic Relief Services arrived there in 2015, they encouraged the community to organize and together identify projects that would improve their lives. Such priorities have included training on potable water, funding for home construction projects and installing irrigation. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

From there, they moved to irrigation.

"It's day and night difference. The production levels of theirs have entirely changed," said Flores, the longtime CRS Honduras official.

"Previously, they didn't offer you anything because they felt shy of what they had or what little they had to offer," he continued. "And now they sit down, they bring out a table with produce and they try to push so many things into your hands."

From 2021-2022, Catholic Relief Services has helped communities install nearly 50 irrigation projects through its Restorative Agriculture in Communities for Economic Sustainability-Disaster Risk Reduction (or RAICES-DRR) Project.

"We have the soil, we can improve it," Flores said, calling irrigation a critical adaptation tool to climate change in Honduras.

"Access to water is access to food," added Díaz, the CRS country representative. "If you have water, your family eats well. If you don't have water, you're really eking out under a very miserly existence and all the problems that come with it" around health and nutrition.

For an irrigation system to succeed and be functional, a community requires at least three years of support, Flores said. The first year focuses on technical infrastructure, the second on training to manage the system and fund maintenance, and the third is when the family or community fully takes over.

Desiderio Vasquez (cowboy hat), a local farmer, and Miguel Flores (right), a senior technical adviser for Catholic Relief Services Honduras, stand on a bridge being built in the Los Hornos community to connect a long and winding rock-strewn road to a farming community on the other side of a creek. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

The approach stresses self-management of their own development, a key component of many Catholic Relief Services initiatives. Establishing Saving and Lending Communities, or SILC, teaches farmers about self-saving and loans. CRS has established nearly 70 SILC groups in the country, with 45% of them run by women.

The SILC groups, which meet weekly and oversee a savings box with three separate locks, use the funds to buy seeds, fertilizer or farming equipment, as well as emergency requests for health and education. Karen Gomez, who coordinates the SILC groups for Catholic Relief Services, said the program shows farmers how to save well, and fosters greater community unity and transparency.

Ormelli Gonzalez, a keyholder with the United Cedros Families SILC group, which earlier this year installed a new reservoir, said having direct savings in the community also makes women less reliant on men for funds.

"Now, we don't have to wait for them to take us to the bank, so we have that advantage. We have access to cash," she said.

The SILC groups are also key in funding larger community projects and are a source of generating income.

A coffee plant grows at the family farm of Wilfredo Hernandez, several hours down an unpaved road outside the town of Santa Ana, La Paz, in Honduras. Coffee is Honduras' largest export. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

"I think these projects can show the impact of what an irrigation system can have on a poor community," Flores said. "They were unable to produce during the summer. There were six months where they could do nothing in their community, but now they can. They can plant."

Along with expanding water access, other CRS projects over the next five years will invest $12.75 million in land and water restoration and sanitation — for example, improving coffee and other crop yields through improved agricultural practices — and $13.5 million in assisting communities affected by weather-related disasters and improving climate resilience.

Catholic Relief Services is far from alone in working on climate adaptation projects in Honduras. NGOs, institutions and the federal government have brought funding for irrigation systems, water harvesting and other mechanisms.

"What we are missing is the sustainability of those projects in time," said Irene Ortega, a climate change specialist with the Honduran natural resources and environment ministry.

She said the government is working with NGOs and civil society organizations to coordinate bringing climate adaptation measures to communities most in need, but it faces challenges in terms of resources and funding. At international climate summits, Honduran delegates have allied with other Central American and developing nations to press for greater attention — and money — toward adaptation efforts, as climate impacts become more prevalent.

In January, U.S. Agency for International Development announced $43 million in aid to Honduras for education and food security. Since 2021, the federal agency has provided roughly $261 billion in humanitarian funding to Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, including for food security, drinking water and disaster preparedness and response.

"We are fighting to establish the importance for [industrialized nations] to see us as highly important in terms of vulnerability," Ortega said. "Not look at us with pity, that we need help, but it's the idea [of] how we can coordinate together to improve the conditions."

One of the biggest needs is the transfer of technologies, both in terms of measuring climate change as well as responding to it, said Mejia of the Honduran Institute for Earth Sciences. One partnership with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has helped the institute to simulate and analyze climate impacts in Honduras. But more is needed, he said, in terms of soil mapping and management, maintaining meteorological stations and creating mechanisms to measure losses from climate change that could qualify for compensation under a loss and damage fund created last year at COP27 in Egypt.

Asked what message he'd send to the U.S., Ayolo, the institute's hydrology specialist, said, "In our small countries, we are not asking to get our problems solved. But if we don't have the tools, please help us have those tools so we can be accountable for our own destiny."

Rony Figueroa is pictured next to an 8,000 liter water harvesting tank he uses for irrigation. With the help of Catholic Relief Services, water access is less of a challenge at Figueroa's farm in central Honduras' Dry Corridor. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Hope for Honduras and beyond

With the help of Catholic Relief Services, water access is less of a challenge at Figueroa's farm.

No longer reliant solely on rain, irrigation systems pump water housed in a 8,000 liter water harvesting tank from a nearby stream, which then is used to water eight plots of land where he grows corn, beans, taro, limes, lychee and plantains. A greenhouse holds rows of tomatoes and green bell peppers. In a pond, he keeps 3,000 tilapia, which provide an additional source of income.

During the busiest times, he's able to employ two to four day laborers. He'd like to expand even more and be able to offer as many as 10 jobs to his community.

"Now more than ever I realize that we can live well in Honduras," he said.

Portrait of the Figueroa Family: Maximiliano Turcios, 60, Mainor Alexis Figueroa, 9, Emilson Figueroa, 14, Rony Figueroa, 35, and Reina Padilla, 35, in their corn, bean and banana plantations that are watered even in the dry season thanks to the assistance of the RAICES-DRR Project. The family uses conservation agriculture practices from the Water-Smart Agriculture program from Catholic Relief Services. (OSV News photo/Oscar Leiva, Silverlight for Catholic Relief Services)

Figueroa was one of the first people Catholic Relief Services supported through its ROOTS Project, which focused on reducing disaster risks. In looking for possible candidates, they sought out those who most needed help and also who could be community examples.

Today, there are five irrigation systems in the community that benefit 300 families. The progress that Figueroa sees in his hometown fills him with hope.

Hope that his harvests will grow and allow him to employ more people. Hope that his success can be replicated with neighbors. Hope that their Honduran community can offer, and sustain, good lives that will lead people to choose to stay. Hope that his soccer field will once again fill with the energy and aspirations of youth.

Figueroa allows himself to dream that one day his oldest son, Mainor, or another kid who kicked a soccer ball around his field, may leave — like he did — not because of poor harvests or fleeting rain or limited work, but to represent Honduras, their home country, in the sport's biggest stage, the World Cup.

"I would like that some of the guys in here can follow that dream."