A woman from the Indigenous community of Huancuire and her daughter camp with others near the Las Bambas copper mine in Apurimac, Peru May 9, 2022. It was part of a protest to demand that their ancestral lands be returned to the communities. (CNS/Reuters/Angela Ponce)

The idea of creating a new national park would seem a more-than-welcome proposal in the middle of an international biodiversity summit in search of solutions to reverse global trends of ecosystem destruction.

In general, designating land as a park would help prevent development and extractive activities from happening within its borders, preserving a scenic natural environment, and the animals and plants that call it home, for current and future generations.

But the prospect of new protected areas raises alarms for many Indigenous communities around the world. The problem isn't necessarily the park, they say, it's a matter of how and where it's established, and whether they have a voice in it.

"For centuries, Indigenous peoples have been squeezed into smaller and smaller pieces of land. And yet those pieces of land are still being taken and stolen from us," said Ellen Gabriel, a land defender and member of the Kanien'kehá:ka, or Mohawk, Nation, during a Dec. 14 press conference at COP15, the United Nations biodiversity conference, in Montreal.

Their worries are rooted in examples of Indigenous communities being forced from their traditional lands in the name of conservation. At a daylong event at the COP on Dec. 14, Indigenous leaders recounted example after example, from hill tribes in northern Thailand, to people in Nepal and Cambodia arrested for trespassing in parks, to Masai communities in Tanzania being forced from their ancestral lands for a new wildlife corridor and tourism, to land disputes throughout Canada, including the Oka Crisis in 1990.

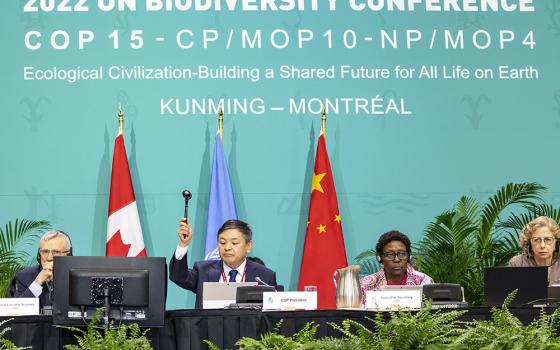

Throughout the COP15 U.N. biodiversity summit, Indigenous leaders have called for greater respect and recognition of their rights to traditional lands in decisions about protected conservation areas. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

"These parks, they're great for recreation. Everybody can come snowshoeing. … But for Indigenous people, we don't have any rights," Gabriel said.

The concern is at the core of one of the headline-grabbing targets among more than 20 proposed in the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework under negotiation here at the COP15 United Nations biodiversity conference. The framework has been called a potential "Paris moment for nature" that could catalyze action to halt and reverse biodiversity loss in a similar way as the Paris Agreement on climate change.

The goal, included in Target 3 and dubbed the "30x30 plan," states that at least 30% of lands and waters be set aside for conservation by 2030, especially those deemed critical ecosystems. Target 3's language is among many unresolved issues, including what percentage and which lands qualify. The latest version of the text includes references to respecting the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities, as well as recognizing their contribution in their lands' management, but remain in brackets — meaning nations have yet to agree on them.

Proponents say such land protections are critical to halt destruction of ecosystems and species loss from increasing extractive practices like mining and logging, and that these areas also play an important role in limiting the impacts of climate change. The latest reports from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated at least 30% of land and sea need to be preserved if the planet is to meet the climate goals under the Paris Agreement, namely holding global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

While some environmentalists, as well as Indigenous leaders, have pressed for the percentage of lands and waters to be increased — at least 50% has drawn supporters, and the Amazonian Indigenous group COICA has called for 80% of the rainforest conserved by 2025 — numerous Indigenous-led organizations have expressed major concerns, with Indigenous leaders in a letter to COP15 warning if constructed without recognizing their rights it could amount to "the largest land grab in history."

Members of Indigenous communities around the world took part in a daylong discussion on the Post-202 Global Biodiversity Framework on Dec. 14 at the COP15 United Nations biodiversity conference. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

The International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity has called for strong, clear language in Target 3 that recognizes Indigenous territories and customary lands and waters as distinct from categories like protected areas or other effective area-based conservation measures, and that their rights are also recognized and respected.

A key aspect is free, informed and prior consent.

"When we talk about free, prior and informed consent, it is actually a substantive process that allows Indigenous people to have their own collective decision-making process with respect to our rights, for our collective rights," said Joan Carling of Indigenous Peoples Rights International during the Indigenous-focused event.

That means decisions on how their lands are utilized. And just as important, what they can do on them.

"When we say we have the right over our lands, territories and resources, that means we have the right to decide how to manage, use and conserve our resources. It cannot be that we have our right to land but we are prevented from using it," Carling said.

But, she added, that often describes the situation at play with national parks.

Advertisement

Many of the Indigenous people who spoke at the COP15 event described how land use restrictions in federally designated protected areas and parks prevented Indigenous communities from hunting and building homes in their traditional lands or from using natural resources within them. In some cases, that has led to conflicts, arrests, displacement and deaths.

"What is our experience of national parks? When we look around different parts of the world, how many, how many thousands, if not millions, were evicted? … This is the reality in a lot of national parks," Carling said.

Indigenous leaders have argued that restrictions in environmental preserves that overlap with their land not only violate their rights under several international laws and treaties, but are counter to goals of implementing successful conservation measures. While eco corridors are seen as essential for preserving biodiversity, Indigenous communities are quick to say, so are they.

A commonly cited statistic from the World Bank notes that while Indigenous peoples make up just 6% of the global population, roughly 80% of the world's biodiversity exists in lands they occupy.

"Today, Indigenous peoples' and local communities' actions are effectively reducing the loss of biodiversity. Much of the success to the efforts are based on their traditional knowledge and control over their territories and waters," said Lakpa Nuri Sherpa, environment program coordinator for Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact.

A panel discusses Indigenous contributions to biodiversity conservation at an event Dec. 14 at the United Nations biodiversity conference. Pictured, from left, are Lakpa Nuri Sherpa, Nataly Domicó, Nittaya Earkanna, Harold Rincon Ipuchima, and Joan Carling. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Faith groups have been supportive of Indigenous priorities for the Global Biodiversity Framework. Within their own policy proposals, endorsed by more than 50 religious-based organizations, the Faiths at COP15 coalition have stressed that human rights be included throughout the document, not just limited to a single target or its preamble.

"Indigenous peoples still need to be empowered with these international mechanisms to manage the lands that are their traditional territories in the ways that their traditional ecological knowledge allows," Sabrina Chiefari, creation care animator for the Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto, told EarthBeat. She added that means without interference of corporate interests or government policies that often run contrary to traditional Indigenous conservation practices.

Pope Francis has been a vocal proponent of greater listening to the wisdom of Indigenous peoples, especially around ecological matters.

In his July visit to Canada, prompted by calls for the Catholic Church to apologize for its role in the abuses Indigenous peoples faced in church-run residential schools, Francis embraced turning to "Indigenous wisdom" in the face of global challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, saying on protecting the environment, "the values and teachings of the Indigenous peoples are precious."

During his January 2018 visit to the Peruvian Amazon, the pope in a meeting with Indigenous peoples famously issued a stirring defense of Indigenous rights and a scathing rebuke of both extractive activities and "certain policies aimed at the 'conservation' of nature" that fail to consult the people living there, whom he called "a living memory of the mission that God has entrusted to us all: the protection of our common home."

"Those of us who do not live in these lands need your wisdom and knowledge to enable us to enter into, without destroying, the treasures that this region holds," Francis said.

Grandma Losah of the Tla'amin Nation pray with Maori women of New Zealand over a 750-year-old Douglas fir from Vancouver Island in British Columbia, a Canadian province where 97% of old growth forests have been cut down. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Dominican Sr. Mary Catherine Rice said that the idea of integral ecology that Francis describes in his encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" applies to how COP15 deliberates conservation initiatives, where decisions made in Montreal will impact communities around the world.

"Everything affects everything else. … It's a domino effect," she said.

Rice added that her Dominican congregation in Sinsinawa, Wisconsin, has sought to develop relationships with Native tribes in their region as they explore their own land restoration and preservation projects.

During the Indigenous-led event, representatives of tribes highlighted the ways their communities have conserved their lands, in many cases for centuries, and often due to a spiritual connection with the land.

"Our cosmological vision defines our relationship with nature," said Vyacheslav Shadrin, chair of Yukaghir Council of Elders of the republic of Sakha-Yakutia, in Russia, who described their rules and customs that their people follow to prevent overuse of resources.

The event closed with a screening of the documentary "Keepers of the Land," which highlighted how the Kitasoo/Xai'xais Nation, on the central coast of British Columbia, Canada, has worked to manage and protect their own lands, including achieving in July a ban on black bear hunting in part of the Great Bear Rainforest that includes part of their lands in an effort to save the spirit bear — a black bear with an all-white coat that holds deep cultural significance for Kitasoo/Xai'xais and Gitga'at people.

Chief Doug Neasloss of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais Nation said that the motivation for the film was to present the land to the community and preserve elders' stories for future generations to understand their own responsibilities to the land.

"But I also wanted to use this as well," he said, "to show the rest of the world … as Indigenous people, we are driving a lot of that work [on conserving biodiversity]. We're driving the science and bringing traditional knowledge and local knowledge."