Abandoned building in Kingwood, West Virginia, in a 2015 photo (Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress)

A flood ravaged Preston County in rural West Virginia in 1985. In its wake, a Catholic youth minister and a group of teen girls made the trip from New Jersey to help dig out basements and make other home repairs to help people in the area recover. The group kept returning every summer, soon numbering some 700 teen volunteers. This continued until the COVID-19 pandemic forced Fr. Andy Switzer, pastor of St. Sebastian in Kingwood and two smaller mission sites in the county, St. Edward the Confessor and St. Zita, to cancel it for 2020.

"That's probably been harder than not having Mass," Switzer said of the decision. Perennial relationships between rural parishes and service groups from outside dioceses are part of the lifeblood of the church in Appalachia. Switzer, 40, told NCR that not only was the program a way for young people to get fired up for social justice, but that people truly rely on it.

"The poor will suffer now," Switzer said. "What do I do? There are people who might not have a roof this winter because of the pandemic."

Exterior of St. Sebastian Church in Kingwood, West Virginia

The cluster of churches Switzer serves, referred to locally as the Catholic Church in Preston County, didn't reopen until early June, with the favored path being to reopen only in the larger, central site, at least at first, and keep the missions closed, in part because of the logistics of keeping three locations sanitized and safe at all times.

"Right now, medical professionals are leading Mass more than I am," Switzer said. Health professionals, he said, are making determinations about the time and place of worship, something he sees as keeping with laypeople taking on an increased leadership role in the church.

A little over 40 miles away, All Saints Catholic Church in the small town of Bridgeport, West Virginia, is living the reality of the rigors of reopening. Fr. Walt Jagela, pastor, told NCR that attending Sunday Mass now requires people calling ahead to the parish office, only doing one Mass on Sunday, limiting the time people can be in the building before Mass starts — hospitality ministers escort people from their cars to their pews — and providing masks for those who don't have them.

"Thank goodness we have the staff that we do here," Jagela said. "It ran like clockwork once we got into it." But he also tried to prepare his people. "Mass is not going to look and feel the same," he said of the transition. "There is definitely that grieving process," because the congregation at All Saints misses certain aspects of the Mass, such as the sign of peace, which the diocesan guidelines in Wheeling-Charleston eliminated.

Jagela, 53, noted that his most serious concern is seeing older parishioners and people his staff know have health conditions walking in the door.

"Those are the ones that are going to come!" Jagela said of the commitment of a generation that had their Sunday obligation drilled into them: "I have to go to Mass. I have to be present there. I have to attend Mass. Or I have to hear Mass." He noted that he even gets calls from older parishioners requesting confession, only to learn that their concern is having missed Mass.

Pews of St. Sebastian Church in Kingwood, West Virginia (Provided photo)

Back in Preston County, Switzer said he also has real concerns for the seniors who make up about 60% of St. Sebastian's congregation and about 80% of the other two sites. His fear is that people living in a rural area with a lower infection rate than even the rest of the state will think COVID-19 only happens in other places.

"The temptation is just to notice what's happening right around me and my community," Switzer said, noting that he's "seeing reckless behavior in the community" such as not wearing masks in stores.

Switzer echoes those who see the pandemic as a wakeup call to a more Laudato Si'-infused perspective of people recognizing their place in an interconnected web of life. He says he has been avoiding using language suggesting God caused the pandemic, as that carries the risk of fundamentalism.

"We really do have to begin to think about God, about the earth, about the world in an evolutionary way," he said. He added that even the church has evolved. "This is a time of the domestic church ... families gathering at home for worship ... some of the themes we see in the Acts of the Apostles, getting back to our roots, if this mess allows some of that to unfold."

Switzer also sees the Second Vatican Council as having a guiding role as the church navigates the way forward. Dei Verbum — the council's Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation — put major and renewed emphasis on the importance of Scripture, and the suspension of public Masses has meant Catholics have had to seriously rely on that aspect of their faith in ways they never did before. Switzer also sees a widespread distortion of religious freedom — which Vatican II addressed in the document Dignitatis Humanae — in the debate surrounding church closures.

"The government can't tell me that I have to worship," he said. "Worship is my free response to God."

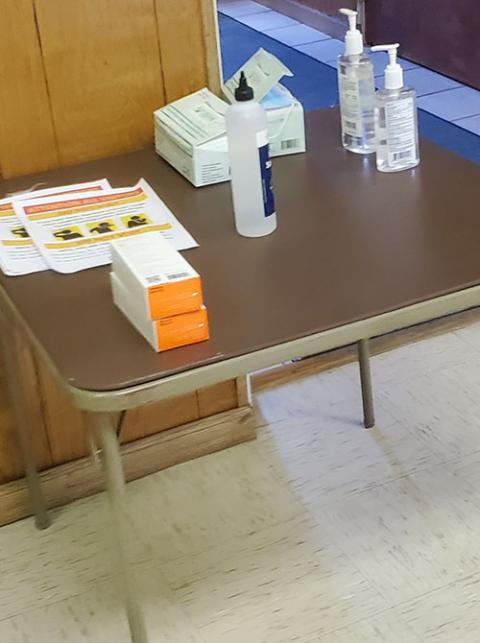

Hand sanitizer and other supplies at St. Sebastian Church in Kingwood, West Virginia (Provided photo)

Vatican II also counseled the church to utilize modern media, which the pandemic has also forced and where Switzer says he has fallen short in keeping up to date.

"Had I known this was coming and could have done it over it again … I would have wanted to know better how to navigate that," he said. "This has been a learning experience for me. It's opened me up to things I hadn't seen and done before." Technology is a particular challenge for the rural church, he also noted, as the area doesn't enjoy consistently good internet access.

Injustice against the poor is a theme Joe Boland, vice president of mission for Catholic Extension, the Chicago-based organization that aids poor mission dioceses, holds closely with the pandemic and sees in rural dioceses across the country, not just those in Appalachia.

"It's often the poor that miss the church the most," said Boland. "They're suffering the most. They're also the ones that are going to have the longest period of recovery — health wise and economically as well."

Boland sees variations on these realities playing out among migrant farmworkers in Washington state, meatpacking plant workers in the Deep South and on Navajo reservations. He also sees the institutional church facing a possibly "severe reckoning" as Payback Protection Program loans through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security or CARES Act run out in June.

Advertisement

"It might take a good while for us to get back," Boland said, noting that some in the dioceses in contact with Catholic Extension are discerning what it would look like to get back to their missionary roots, even if by necessity. "Our notion of what institutions look like — leadership, structures, that kind of thing — might be radically altered for at least the near-term future."

But here Switzer sees Pope Francis' poor church for the poor coming to bear. "Is this not making us look at what we need and don't need?" he asked. Even the cancelled summer repairs program that brings hundreds of volunteers, he points out, raises the question of why there is still so much need for it all these years later.

"We've been too much on the leg of charity and not enough on the leg of justice," he said, adding that, if anything, economic conditions in the county are worse than they were in 1985, which suggests neglect of the Gospel mission to take care of the poor. This, he notes, has implications for the Eucharist his people have gone so long without: "If we're not focused on our mission, we're not doing it justice."

[Don Clemmer is a writer, communications professional and former staffer of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. He writes from Indiana and edits Cross Roads magazine for the Catholic Diocese of Lexington, Kentucky. Follow him on Twitter: @clemmer_don.]