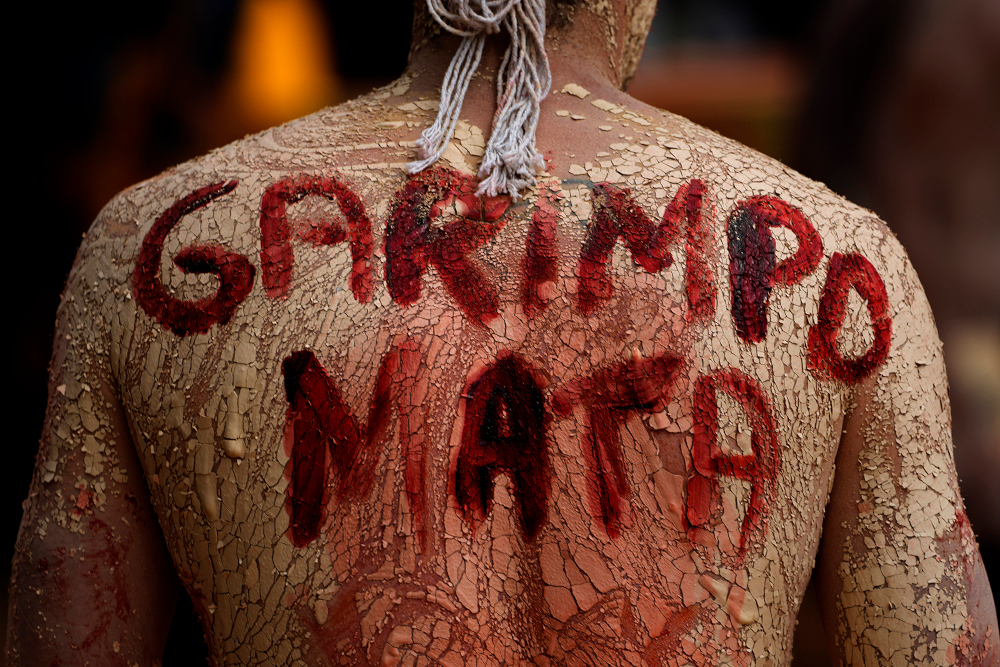

An Indigenous man with a phrase in Portuguese painted on his back that translates to "Mining Kills," participates in a protest against the increase of mining activities that are encroaching on his land, in front of the Ministry of Mines and Energy, in Brasilia, Brazil, Monday, April 11, 2022. (AP/File/Eraldo Peres)

As the ecological crisis in Brazil continues to get worse, the country's Roman Catholic bishops have become more vocal about its causes, denouncing collaboration between government officials and corporations to carry out destructive mining projects in areas occupied by Indigenous peoples.

On May 5, Bishop José Ionilton Lisboa de Oliveira of Itacoatiara, in Amazonas state, published an official decree saying that his diocese would not accept "financial support, either in cash or in other goods, from politicians, logging companies, mining companies … that contribute to deforestation and to the expulsion of Indigenous peoples, "quilombolas" (descendants of escaped African slaves), riverside communities, and small farmers from their lands."

Though intended for internal distribution in his diocese, Brazil's media caught wind of de Oliveira's decree, and it has gained attention across South America.

The bishop said he never expected his decree would "reverberate so much or that it could incentivize other bishops to do the same." But he hopes that other bishops of the Amazon region will agree to a collective statement when they gather in September.

Since the Vatican's Synod for the Pan-Amazon Region in 2019, bishops from Brazil's Amazonian region have been discussing ways to strengthen their stance against deforestation. "Of course, bishops act independently," said de Oliveira, but the reaction to his decree signaled "our adherence to the synod's conclusions," he told Religion News Service.

Advertisement

Applying the Vatican's guidance on the Amazon has not always been easy, said de Oliveira. When he took office in 2017, he noticed that the local communities had not studied Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical on the environment, Laudato Si'.

"We organized meetings with all of our parishes and read it together. Later, we established that we would implement 12 recommendations based on the document," said de Oliveira. The discussions addressed financial donations, the creation of ecological education programs and reducing garbage.

"But after a few years, nothing had changed," he lamented.

With local and national elections set for October, de Oliveira, the president of the Bishops' Conference's Land Pastoral Commission (or CPT in Portuguese), has been watching the rising violence in Amazonian communities that are being invaded by ranchers, miners and loggers.

According to the pastoral commission, 109 people died as a result of land conflicts in 2021, a huge increase from 2020, when just nine people died. Those figures include homicides as well as deaths indirectly related to rural violence, such as those caused by the poisoning of water and fish with heavy metals, a byproduct of mining operations.

In April, 462 square miles of the Amazon were destroyed, according to Imazon, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the rainforest's conservation. This represented a 54% growth in comparison to April 2021, making it the worst April in 15 years.

More than 2,600 miles to the southeast of de Oliveira's diocese, Auxiliary Bishop Vicente Ferreira of Belo Horizonte, in Minas Gerais state, is planning similar efforts.

Helicopters hover over an iron ore mining complex to release thousands of flower petals paying homage to the victims killed after a mining dam collapsed in Brumadinho, Brazil, Feb. 1, 2019. The tragedy also stoked protests from Brazilian indigenous groups who contest the misuse and clearing of indigenous lands, often on religious grounds. (AP/Andre Penner)

"Beginning with Catholics, we have to raise awareness about the need to divest from mining," Ferreira told RNS.

Ferreira is the secretary of the Bishops' Conference's Special Commission on Integral Ecology and Mining, created in 2019 after the collapse of a tailings dam in Brumadinho that took the lives of 270 people and spilled 423 million cubic feet of mine waste into the Paraopeba River basin.

In January, when heavy rains caused major floods in the region and many houses were covered with mud, Ferreira visited people in the area and said the effects of the 2019 tragedy were still apparent.

"That mud brought with the flood was not real mud, but a toxic mass of tailings mixed with water. The company talks about reparation measures, but some things are irreparable: the lost lives and the contaminated ecosystem," Ferreira said.

"Mining should be profoundly changed in Brazil, because there is something inherently unsustainable in it," said the bishop.

At the end of March, he joined a delegation of Latin American religious leaders on a visit to five European countries, where they campaigned against investment in mining. The group met with political and religious leaders, including Cardinal Jean-Claude Hollerich, head of the European Union's Commission of Bishops' Conferences, as well as officials at the Vatican and international Catholic charitable agencies.

Ferreira wants to see Brazil's Catholic hierarchy take more radical measures against mining pollution, pointing to the recent decision by the church in the Philippines to stop receiving donations from environmentally destructive industries.

"Our greatest challenge is to … carry out concrete actions to face that enormous power (of the mining industry). We still do not know how to stop that Goliath," he said.

Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, speaks during a ceremony at the Planalto presidential palace, in Brasilia, Brazil, Tuesday, July 13, 2021. (AP/Eraldo Peres)

Archbishop Roque Paloschi of Porto Velho, at the northern reaches of the Amazon basin, has been another strong critic of Brazilian mining companies. He heads the Bishops' Conference's Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI in Portuguese) and has witnessed firsthand the impact of mining operations in Indigenous areas.

"Mining represents death for the Indigenous peoples," he told RNS. "It contaminates their water, opens the door for the consumption of alcohol in their villages, resulting in the rape of women and girls."

Paloschi cited the case of the Yanomami in the Amazon. Approximately 26,000 members of the Indigenous group have to share their land with an estimated 20,000 workers for illegal mining operations.

The mining spreads diseases such as malaria, thanks to abandoned mining pits that become breeding ponds for mosquitoes. Rapes and homicides have become more common. The rivers have been contaminated with mercury, and the heavy machines used by the invaders drive away animals the Yanomami depend on for hunting.

CIMI and other civic organizations have been protesting against a bill introduced by President Jair Bolsonaro in 2020, currently under consideration in Congress. The bill proposes to legalize mining and other industrial activities in Indigenous territories, which current legislation forbids.

Bolsonaro's bill would contribute to the further deforestation and destruction of natural habitats, activists argue, given that Indigenous territories now serve as sanctuaries.

Paloschi believes that most Brazilian Catholics do not understand how extensive deforestation in the Amazon is, or the full implications.

"Brazil is a country that bears the marks of slavery and of the colonial system. Many people think that the Indigenous' way of living is not right. We still have a long way to go in the church in order to become conscious about the need to protect God's garden," he reflected.