French Cardinal Philippe Barbarin of Lyon arrives at the courthouse Jan. 7 in Lyon. Barbarin and others were on trial for failing to discipline a local priest who allegedly abused children while running a Scout group in the 1980s. (CNS/Reuters/Emmanuel Foudrot)

One of France's most prominent bishops, Cardinal Philippe Barbarin, is likely to be acquitted of charges of not denouncing a priest who sexually abused children between 1971 and 1991.

At the end of his four-day trial, Jan. 7-10, in Lyon, public prosecutor Charlotte Trabaut announced she would not ask for his conviction. Even though the president of the tribunal is not bound by the prosecutor's stand, it seems likely that the cardinal will be acquitted.

French judicial authorities opened a case against Barbarin in 2016, in the name of the French state. The court closed it, invoking statute of limitation.

Then the group named La Parole Libérée ("the word made free"), brought the charges in a private prosecution, in their own name, as parties civiles — private victims — after discovering, in 2015, that Fr. Bernard Preynat was still working with young boys. They thought this personal action could convince a court of the prejudice they suffered, knowing most facts fell under the statute of limitation.

Stern and slightly stooped, Barbarin, 68, said he was not guilty of anything: "I never tried to hide and certainly not cover anything." He then kept quiet, letting his lawyers speak for him during the whole procedure and explain he only made mistakes in managing the case and would act differently today.

He did not ask for forgiveness from the victims of Preynat, whom Barbarin was responsible for, since the priest served in his diocese.

For La parole Libérée, the purpose of this legal action was to tell publicly what had happened. For two days, the court heard moving testimonies from nine of Preynat's victims, who described, painfully and with graphic details, how they were sexually assaulted.

Victims unite

The long history of this case begins in 1971, when Preynat was appointed as a parish priest to Saint Luc, a new church in a rapidly growing neighborhood of Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon, where he became chaplain of a troop of scouts, boys and girls.

A charismatic man, Preynat was very popular with a lot of parents, who thought he did a great job organizing activities for the scouts and taking them to camp. His authoritarian ways were reassuring at a time when the church was in the wake of Second Vatican Council. Liturgy was changing, a lot of priests left to get married, and parishioners were disoriented.

Preynat often became a friend of the family. Some thought he was a little too close to little boys, but nobody imagined for a moment what was happening in his office, on the first floor of the rectory, when he would ask one of the boys to come and see him.

Advertisement

From 1979 to 1991, he regularly abused boys, even raped some of them. Sixty-five cases have been documented by La parole Libérée, and there are estimates of about 100 victims altogether.

As is often the case, the boys never talked about the abuse, either to their parents or their peers. But in early 1991, when the mother of 11-year-old François Devaux overheard her son talking with his brother, bragging about being a favorite of the priest and telling him, "He even kisses me on the mouth," Devaux's parents were shocked. They asked him questions and started talking to other parents. Some of them echoed their worries, others defended Preynat.

Devaux's parents asked for the priest to be sent to another mission, away from children. When nothing happened, Devaux's mother sent a letter by registered mail to the archbishop of Lyon, Cardinal Albert Decourtray, writing she was going to the press if Preynat was not removed.

A few weeks later, the priest was appointed as chaplain to the congregation of the Little Sisters of the Poor, a religious community caring for old people.

Decourtray thought the matter was closed. Preynat told the cardinal he would never do anything wrong again. The cardinal urged the parents not to file a civil complaint, for the sake of the unity of the church.

Six months later, though, contrary to his promise to Devaux's parents, Decourtray appointed Preynat to a country parish, away from the city of Lyon.

Decourtray died suddenly in 1995 and was replaced by Cardinal Jean Marie Balland, who died three years later. Cardinal Louis-Marie Billé served as archbishop from 1998 until he died in 2002.

When Barbarin became archbishop of Lyon in 2002, he met Preynat and asked him about his past. "He told me he was ashamed and had never done anything since 1991. I believed him. I trusted him," the cardinal is quoted as saying to journalist Isabelle de Gaulmyn senior editor of the French Catholic daily La Croix, and the author of Histoire d'un silence, the most comprehensive and well documented investigation on the scandal.

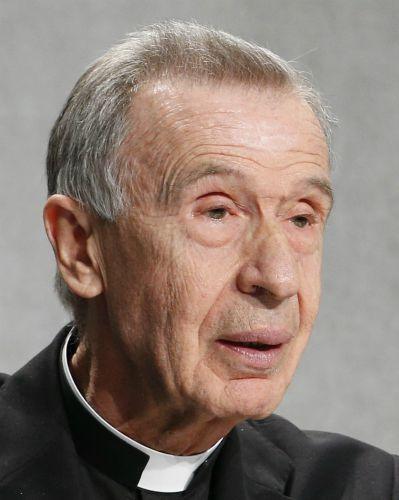

Archbishop Luis Ladaria, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, is pictured May 17, 2018. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Apparently, there was no trace of the scandal in the priest's file, except for the letter sent by Devaux's parents. "This is something which happened before my time," Barbarin would repeat at his trial. "My predecessors dealt with it, I had no reason to reopen the case."

In 2002, the Annual Assembly of French Bishops voted on an important declaration stating that "Priests guilty of pedophile acts … have to face justice," adding that bishops should not stay passive and cover such acts.

Barbarin admitted he knew Preynat was suspected of inappropriate behavior with children. But nobody had sued us, he said, repeating this was for him "a thing of the past." "It wasn't until I met with Alexandre Hezez in 2014 that I understood the problem," Barbarin is quoted as saying by De Gaulmyn in the same interview. "Until then I heard only rumors."

Hezez, one of the founders of La Parole Libérée, was among those who told the court how he was sexually abused between the age of 8 and 11 by Preynat. In 2014, when he recognized Preynat at a parish feast and heard that he was in contact with children, he asked Barbarin for an explanation.

Before taking action, Barbarin asked the Vatican for advice. Rome took several months to tell him to send Preynat, then 74, into early retirement, "avoiding any scandal." Barbarin waited another 10 months to forbid Preynat to celebrate Mass and perform sacraments.

In the meantime, he met with Hezez and proimised him he would take action against Preynat. But it took so long for Preynat to be removed from ministry that Hezez decided to write to Lyon's prosecutor's office, telling him about Preynat's actions. Legal action was then taken.

At the same time, Hezez got in touch with François Devaux and another former boy scout and victim of Preynat, Bertrand Virieux. Together the three founded La Parole Libérée to collect information and testimonies.

De Gaulmyn knew Preynat as a child and wanted to find out why nobody, the victims, their parents, or church authorities, denounced him, since they all told her they knew more or less what had been happening.

"At the time of Preynat, nobody questioned priest's authority. This scandal will enable us to evolve and see priests as they are, normal men, and not put them on a pedestal as we have done for so long," she said in an interview in La Croix, on the eve of the trial.

Vatican side-step

For France, a mainly Catholic country, this trial is a turning point. Most Catholics, religious as well as lay people, are relieved to see such devious behaviors are not a secret anymore. The last day of the trial, Msgr. Emmanuel Gobilliard, auxiliary bishop of Lyon, thanked Devaux for the work his association had done: "Thank you for shaking the church. It needed it." he told him, in front of the cameras, outside the court.

The top Vatican official in charge of sex abuse cases, Cardinal Luis Ladaria, who is among the accused with four close aides to Barbarin, refused to appear in court, because the Vatican invoked his diplomatic immunity.

Barbarin's personality has only added to the hostility. A conservative archbishop who never smiles, he is known to decide everything himself and give his own opinion, ignoring the church's official position.

"A very brilliant mind, but always excessive. People loved him or hated him," said Henri Tincq, a journalist and parishioner in the Val de Marne, a Paris suburb, where Barbarin was chaplain of the Lycée Marcelin Berthelot.

"He was more appreciated by the parents and youngsters who liked his authority and charisma," said Odile Lerolle, who took over part of Barbarin's responsibilities as chaplain of the lycée after he had left for Lyon.

Barbarin's verdict will be rendered on March 7. He risks a three-year jail sentence and a fine of 45,000 euros.

[Elisabeth Auvillain is a freelance journalist in Paris.]