Train station of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, a village on the Vivarais Plateau, France (Wikimedia Commons/Havang)

In the autumn of 1943 a young couple arrived in the plateau village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon in Nazi-occupied southern France, there to dwell in a farmhouse and be among the 5,000 Jews seeking havens of safety in that mountainous region from German military's mass-murdering. Five members of their family from Poland had already been captured and killed.

The village, led by pacifist Christian pastors with firm commitments to nonviolence, would one day be labeled by historians as the town that defied the Holocaust. More stirring, it would be memorialized by the couple's son, Pierre, who was born in Le Chambon on March 25, 1944, and returned in 1982 to research what would become his masterful and enduring documentary film about the Chambonnais, "Weapons of the Spirit." Pierre Sauvage now lives in Los Angeles and oversees the Le Chambon Foundation.

He is not the first intellectual to personally capture and investigate the spirited heroism of the villagers who, in large risks, took in so many Jewish refugees. In 1979, Phillip Hallie, a philosophy professor at Wesleyan University, wrote Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed. On the shelves also are A Good Place to Hide by Peter Grose and Village of Secrets by Caroline Moorehead.

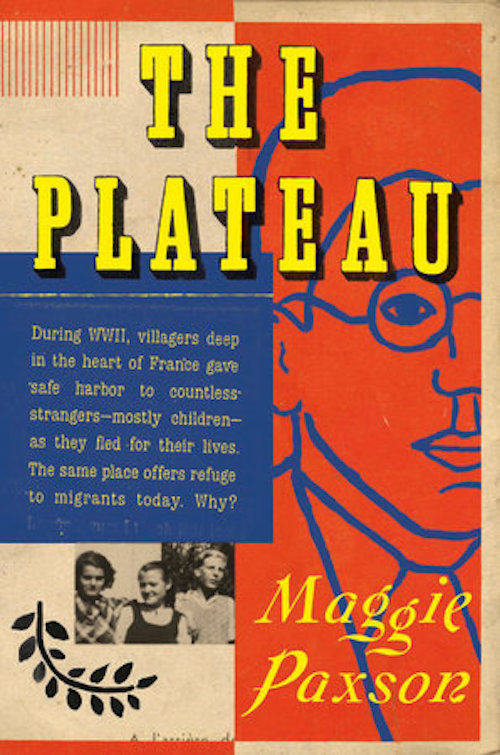

What separates Maggie Paxson from those authors is, first, her background as a well-educated social scientist and anthropologist and, second, her gift for openness in sharing her emotions as she probed deeper and deeper into the lives of people whose stories were commonplace yet inspiring. Her 2005 book, Solovyovo: The Story of Memory in a Russian Village, published after years of fieldwork research, was a worthy example of that.

In the first lines of The Plateau, Paxson writes:

Let's just say that suddenly you are a social scientist and you want to study peace. That is, you want to understand what makes for a peaceful society. Let's say that, for years in your work in various parts of the world, you've been surrounded by evidence of violence and war. From individual people, you've heard about beatings and arrests and murders and rapes; you've heard about deportations and black-masked men demanding people's food or their lives.

… And let's say that the shattering stories had piled on over the years until, at some point, you just snapped. You wanted to study war no more.

As it turns out, it's harder to study peace than you might think. Or it has been for me.

What Paxson is telling us, in flowing and literate passages one after the other, is that she had a conversion: from a war correspondent to a peace correspondent.

And what should be the first surge of energy if not to locate some peacemakers who collectively were committed to nonviolence and get their stories?

Paxson, roused to action in part by having read the Hallie book given to her by an aunt and by touring the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., makes her way to Le Chambon. It would be the first of many prolonged stays, sometimes when she rents an apartment, other times staying with local families, and all the while getting the stories of selflessness and kindness shown to Jewish asylum seekers.

Many were educated at the Cévenol School, founded in 1938 by André Trocmé and Edouard Theis, fellow pastors who, Paxson writes, believed the school "would be part of the Resistance by teaching the children to regard life as precious, to help them look for peaceful resolutions to problems." Word spread about its specialness — Paxson calls it "a little miracle" — and soon a diverse faculty came from a half-dozen European countries.

In addition to young refugees, many children were from families who opened their doors and hearts to fleeing Jews while the school itself did its full share of sheltering. Currently diversity reigns, with students from both far- and near-flung sites: from the Middle East and the Americas to a local plateau hillside.

Paxson is befriended by a Cévenol teacher of political economy named Sandrine who invited the American to speak to her students and talk about what an anthropologist does. "I've been waiting a long time for this chance," Paxson recalls.

Advertisement

In 11 pages of heartfelt prose, Paxson, who has done research at Georgetown University's Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs, attempts to explain to the classes that anthropology is all about "who does what with whom." The children, taking it in, are responsive. Paxson, who grew up in Rochester, New York, and earned degrees from McGill University and the University of Montreal, connects with them easily. She encourages them to speak up, which they do and often with gayety.

Some, Paxson writes,

[P]ipe in shyly now and then about the Germans here on the Plateau during the war, and their grandparents, and how their lives were saved back then. One girl — modest during the class itself, but now eager to speak — approaches me when the day is winding down. She tells me why she comes to the Cévenol School and not to the regular public school in Le Chambon. It's all farmers in her family, and she wants to be a farmer someday, too. Here, she gets to take care of horses right nearby. Would I ever want to come and see them?

Oh, yes I say. I would very much.

Throughout the pages, Paxson graces the readers with candid reflections on both her academic and spiritual lives. Raised by a Jewish mother and a Baha'i father, plus a Christian grandmother, Buddhist aunts and eventually a Muslim roommate, she herself is Baha'i. It is, she writes, a faith, "that teaches the essential oneness of humanity and the essential oneness of all religions, including, of course, the Jewish religion of my birth."

In a poignant moment, she asks,

What am I? Privileged to a life where I have gotten to carry notebooks and make schemes for things? Where I have received polite applause — clap, clap, clap — for writing a book about a group of farmers who have known every dark malady? My analytical wheels keep turning, but it seems to me, more and more, that I am standing on the threshold of something. I will enter, or I won't. And if I do, things will change, and the wheels I have long counted on to bring me along will be loosed.

Without doubt, Maggie Paxson and her many graces will travel well as her journey goes on.

[Colman McCarthy is a former Washington Post columnist. His new book is Opening Minds, Stirring Hearts: the Peace Studies Class]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.