The Pontifical Academy for Sciences, a facility within the Vatican, just concluded a study week on plant biotechnology and its potential to improve the lives of the poor by providing more, and more nutritive, food (see Story).

The study week’s program acknowledged worldwide radical opposition to this technology, stating outright that this was not a standard science meeting, but one designed to “present the potential of plant genetic engineering and to analyze the hurdles responsible for the fact that, so far, product applications to benefit small-scale farmers have mostly excluded the public sector.”

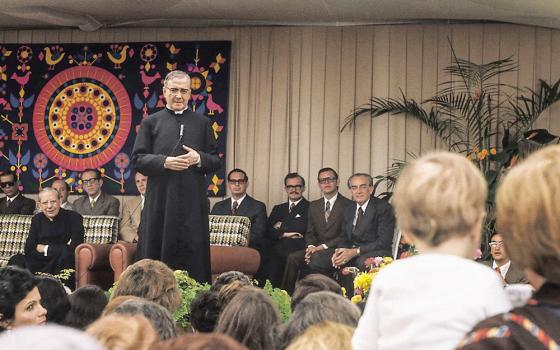

In an interview available on NCR’s Web site, Columban missionary Fr. Sean McDonagh, who organized a small demonstration near the study week site in Rome, asks: “Who are the church’s real experts in this area?” He cites aid and development agencies, such as Misereor, CAFOD, Catholic Relief Services. “They thought so little of this expertise on the ground in the church that they didn’t invite a single person from any one of those agencies.”

If the intent was to explore hurdles and find ways to promote the true potential of biotechnology for the poor in Africa, Latin America or the Philippines, then the absence of any representative from these Catholic agencies, who contend daily with the problems biotechnology is purported to address, is telling, especially within a body that purports to be about science.

The scientific debate about biotechnology continues. If science is anything, it’s a kind of shrewd honesty employed in the endeavor to increase knowledge. Science’s process is iterative. At any stage it is possible that some new consideration will lead scientists to reevaluate, so the investigation is always open to critique.

For years biotechnology corporations have trumpeted that they will feed the world, promising that their genetically engineered crops will produce higher yields, particularly in areas of the world hard hit by hunger.

According to Failure to Yield, a report released in March by the Union of Concerned Scientists, that promise is empty.

This public science study made a critical distinction between potential, or intrinsic, yield and operational yield, concepts often conflated by the biotech industry. Intrinsic yield refers to a crop’s ultimate production potential under the best possible conditions. Operational yield refers to production levels after losses due to pests, drought and other factors. The study reviewed both the intrinsic and operational yields of the most common genetically-altered food and feed crops: soybeans and both herbicide-tolerant corn and insect-resistant corn, known as Bt corn, after the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis, whose genes enable the corn to resist several kinds of insects.

“If we are going to make headway in combating hunger due to overpopulation and climate change, we will need to increase crop yields,” said the report, which concluded that “traditional breeding outperforms genetic engineering hands down.”

The report does not discount the possibility of genetic engineering eventually contributing to increase crop yields. It suggests, however, that it makes little sense to support genetic engineering at the expense of technologies that have proven to substantially increase yields, especially in developing countries.

In addition, recent studies have shown that organic and similar farming methods that minimize the use of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers can more than double crop yields at little cost to poor farmers in such developing regions as sub-Saharan Africa. A report from the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization explicitly states that organic agriculture can address local and global food security challenges. The strongest benefits of organic agriculture, agency spokesperson Nadia Scialabba said, “are its reliance on fossil fuel-independent, locally available resources that incur minimal agro-ecological stresses and are cost effective.”

In a 2000 statement of John Paul II for the jubilee of the agricultural world we find a clear observation on biotech in agriculture. Biotechnologies, he said, “must be submitted beforehand to rigorous scientific and ethical examination to prevent them from becoming disastrous for human health and the future of the earth.”

This is far from thinking of biotechnology as the solution to world hunger and central to development.