Sr. Corita Kent's 1964 work "The Juiciest Tomato of All" is seen at the Theological College in Washington Feb. 17. An art exhibit of her serigraphs, titled "Beauty and the Priest: Preaching with the Artwork of Corita Kent," was on display there through March 3. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Artists are like theologians, but more fun. I loved my art history classes as a college student, not only because of the incredible beauty that would flash across the screen from old-fashioned slide projectors, but because art and architecture helped me better understand theology and spirituality. Our human experience of the ever-evolving mystery of God was made clearer for me through Gothic paintings and cathedrals than the pages of the Summa Theologica. In our own time, artists such as Sr. Corita Kent creatively reveal the inner workings of the Second Vatican Council as it continues to emerge.

A photo of Sr. Corita Kent is seen at the Theological College in Washington Feb. 17. An art exhibit of her serigraphs, titled "Beauty and the Priest: Preaching with the Artwork of Corita Kent," was on display there through March 3. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Which is why 40-plus years later, having spent 11 of those years teaching art history myself, I have fallen in love again for the first time with Sr. Corita Kent, the sassy pop art nun from Los Angeles whose work and fame got her on the cover of Newsweek magazine as an exemplar of "The nun: going modern."

She wasn't just a thorn in the side of Cardinal Archbishop James McIntyre of Los Angeles, she was a whole crown's worth of thorns for the poor guy. He struggled with some of the reforms of Vatican II, such as laypeople speaking English at Mass, and nuns wearing earrings and having thoughts of their very own. Corita, a mature, free-thinking spirit, gave her bishop no small measure of agita, and he gladly returned the favor.

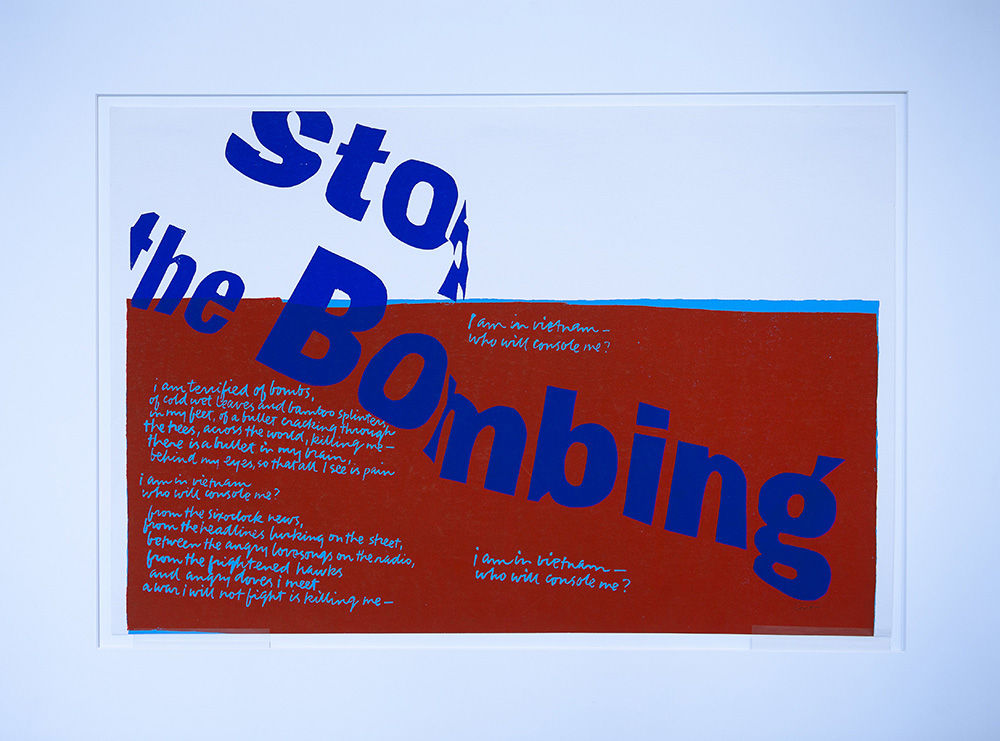

Sister Mary Corita of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary was already a renowned art teacher in Los Angeles when Pop Art and Vatican II each burst on the scene in the early '60s. After seeing Andy Warhol's now iconic Campbell's Soup silkscreens, she was inspired to take religious subjects to a new level, one which merged the sacred and the secular into one, non-dualistic entity. Corita boldly illuminated the incarnate presence of God in our consumeristic, materialistic, fame-obsessed plastic world. She was a woman with Vatican II spunk, a regular Hildegard of Bingen on the streets of Hollywood who used her prolific gifts to speak truth to power and promote peace, justice and Catholic social teaching in the midst of civil rights and the Vietnam War.

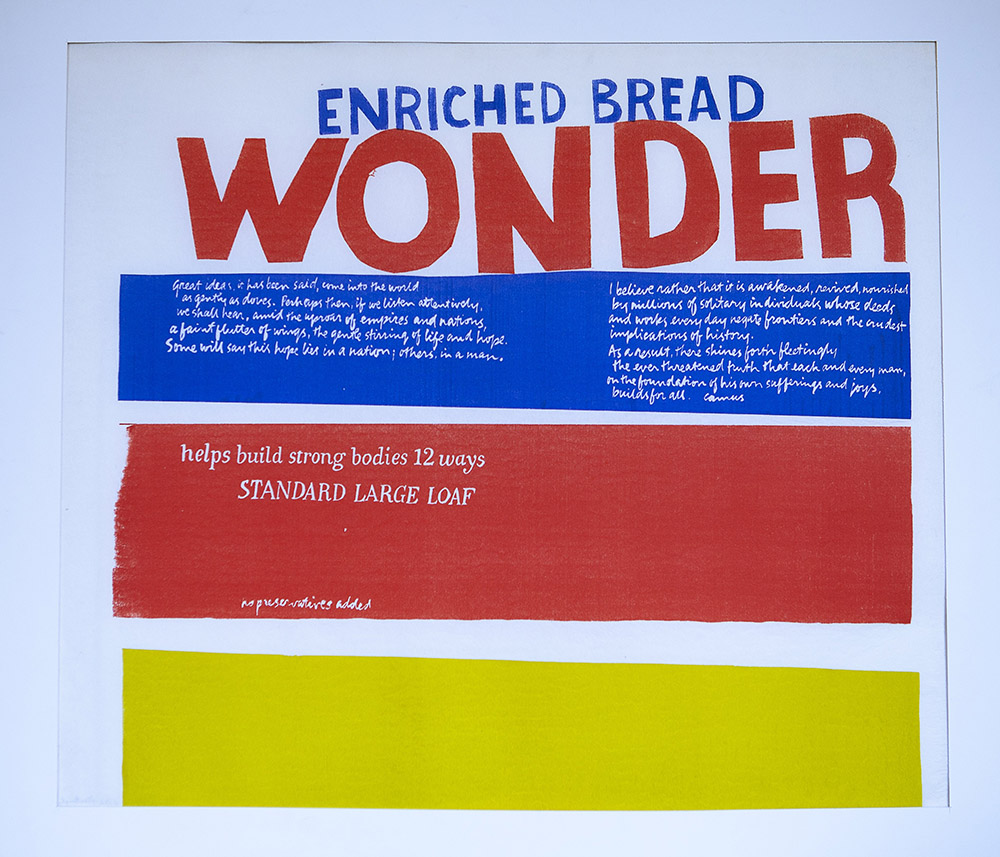

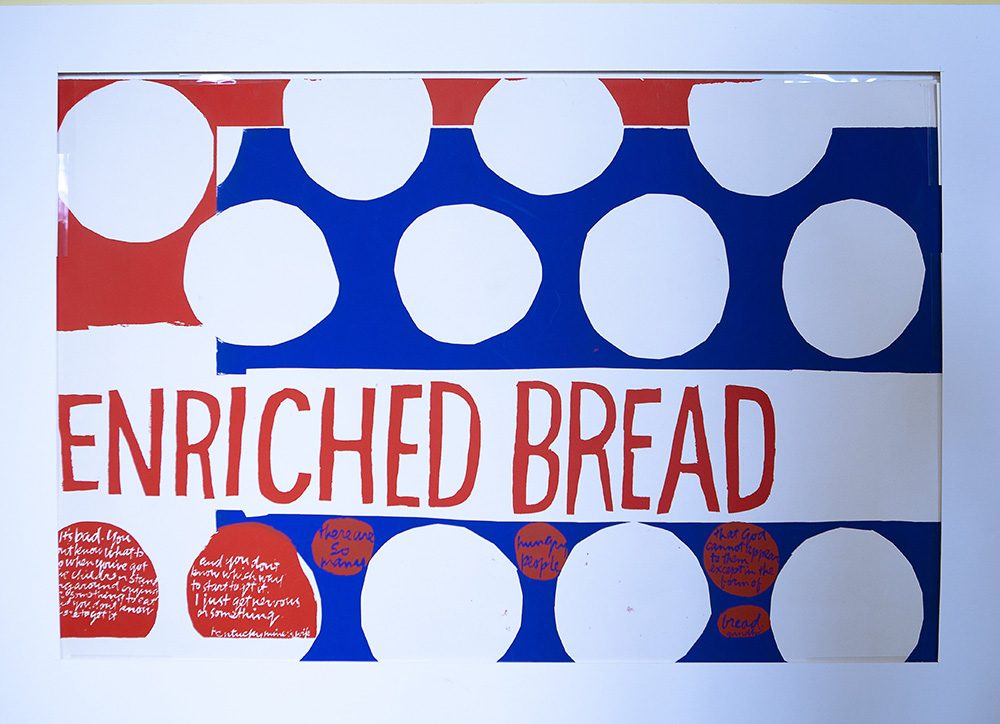

All of a sudden in that swinging decade, God popped up in new guises, no longer locked in a tabernacle to which only a priest had access. And just as Warhol breathed new life into ordinary cans of soup, Corita took the logos and advertising slogans of Wonder Bread to reveal a fresh, modern look at the true Wonder Bread, the Eucharist. "All that is seen and unseen," words heard at Mass in English for the first time, freshly exposed the sacramental nature of ordinary life. "God's not dead he's bread," she famously wrote on one of my favorite prints, pointing out the timeless beauty and power of the Eucharist as something more powerful than a mere weapon of reward and punishment or Sunday obligation.

Recently, in the space of one week, I made two pilgrimages to Theological College in Washington to visit an exhibit of signed, original prints by Corita Kent. It was organized by my friend and rector of the seminary, Fr. Dominic Ciriaco, who was promoting Corita's art as an inspirational source for homilies and preaching. On my first visit, I spent one whole morning completely alone with Corita, a cup of coffee, my prayer journal, and sketchbook. Pure heaven!

"The Only Rule Is Work," a watercolor and pen and ink work by Mickey McGrath (Provided by Mickey McGrath)

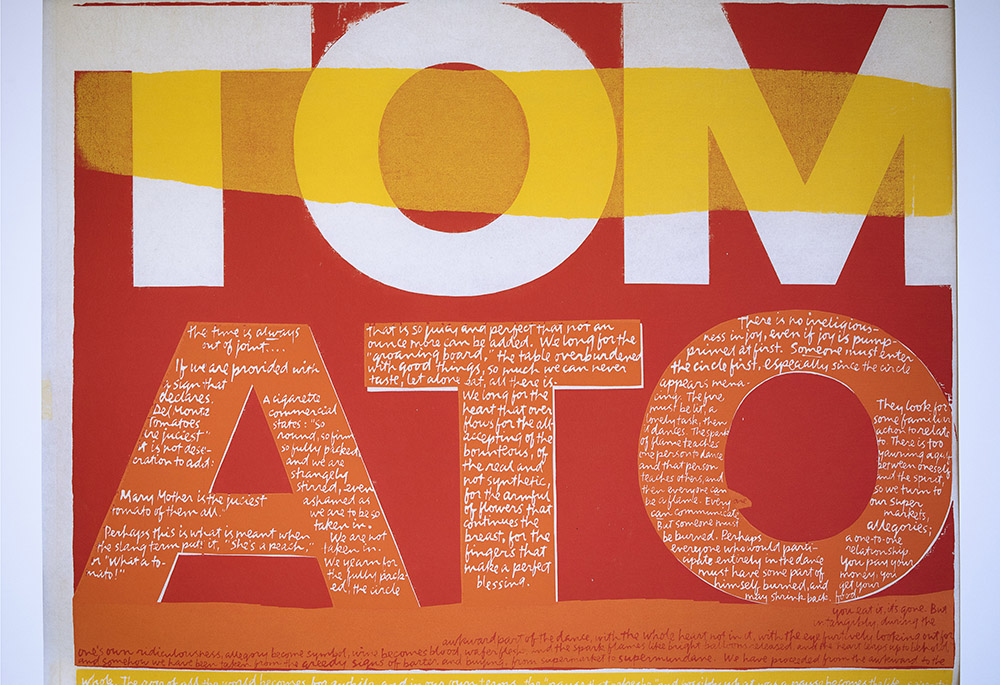

On the wall facing me was a print with the word "TOMATO" in bright red color. Written on it in smaller letters, it states that "Mary Mother is the juiciest tomato of them all," referring to an ad campaign for tomato sauce at the time she created it. Once again, she linked the sacred and the profane in ways that proved appalling to more linear-thinking churchy types. It is the very image that broke the straw of the cardinal's back whose angry response ultimately led to Corita's departure from the convent and the dissolution of the community of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of Los Angeles.

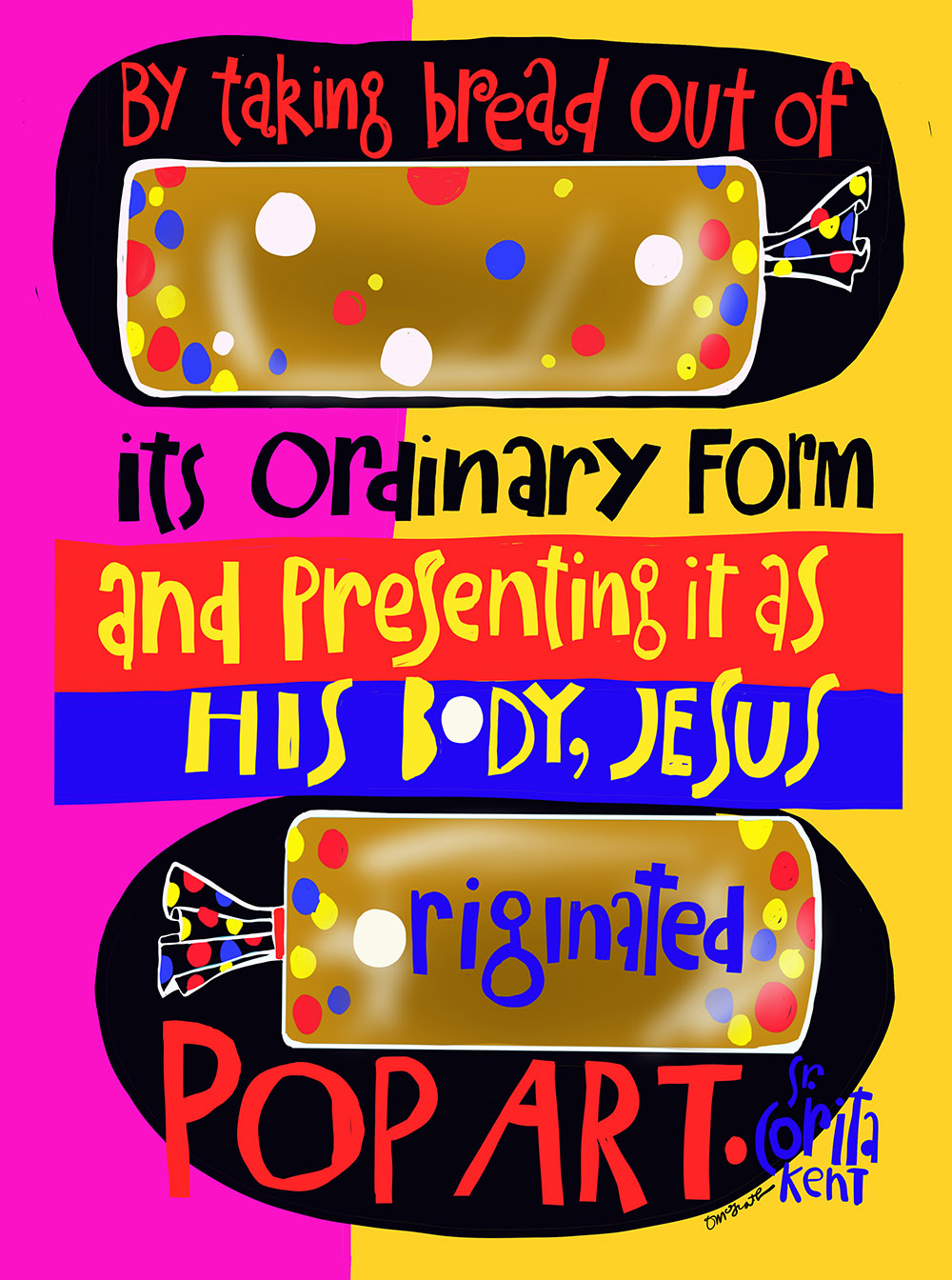

"Wondrous Bread from Heaven," a digital image by Mickey McGrath (Provided by Mickey McGrath)

On my second visit a week later, I traveled with three pilgrim/friends: a nun and two priests, two of whom are Franciscans, all three of whom are huge Corita fans. There we sat at Theological College in a spacious room with high Gothic windows while clerically clad seminarians passed by in the hallway. And while it wasn't exactly the setting I would have ever expected in a million years to finally encounter Corita Kent in person, it was the ideal setting because it exposed through beauty so many parallels between her tumultuous times of church reform and our own.

"Pop Body of Christ," a digital image by Mickey McGrath (Provided by Mickey McGrath)

I thought of Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle, another Los Angeles mystic with pop art spirit, who writes: "The point of the Incarnation is that Jesus is one of us in the ordinary." I am sure "G-Dog" and Corita would get on famously — along with Daniel Berrigan, who was both Corita's friend and Greg Boyle's confrere. He once said, "The great revolutionary virtue is endurance."

And I'd better invite Dorothy Day to this gathering of spirits because she, like Corita, loved Daniel Berrigan. Last but not least on the guest list of my imaginary heavenly banquet is none other than Cardinal James McIntyre because he was a devoted and generous supporter of Dorothy Day's! Who knew? What an interesting dinner party it would be with Wonder Bread on the menu.

Advertisement