An elderly Ukrainian woman looks on after Russian shelling in Mykolaiv, Ukraine, June 29. (AP/George Ivanchenko)

During Russia's terrible and ongoing total war on Ukrainian civilians, it has become clear that one strain of so-called "realist" thought in international relations theory is a source of confusion and an obstacle to human progress. In a May 19 interview, published in La Civiltà Cattolica and the newspaper La Stampa on June 14, Pope Francis reported that one (unnamed) foreign leader told him that "perhaps" NATO may have provoked the war "by barking at the gates" of Russia, which remained an imperialist power determined to control its region.

Patriarch Kirill, the leader of the Russian Orthodox Church, has been criticized by the Vatican and many others for offering similar excuses, including gay pride marches, to justify Vladimir Putin's campaign of mass murder in Ukraine.

The pope has not endorsed this "shared blame" objection to NATO's expansion after the end of the Soviet Union; rather, he is mainly concerned that this conflict could become the initial phase of a new world war. Moreover, popes generally see their role in foreign affairs as aiming at peaceful reconciliation among enemies. As scholars have noted, the Holy See exercises a unique kind of "soft power" in international relations.

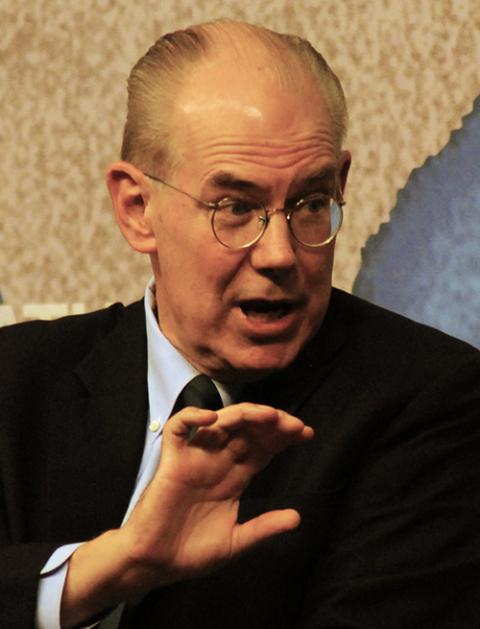

But the controversy surrounding Francis' remark derives from its resonance with the political scientist John Mearsheimer's "offensive realism" theory that "great powers" will generally do whatever is necessary to dominate their region of the globe as a means to their own national security — whatever they pretend to believe about the human rights of civilians and codes of international law, which have banned annexation of territory by force for over a century.

John Mearsheimer (Flickr/Chatham House)

In his infamous New Yorker interview, and in a lecture widely circulated online, Mearsheimer blamed NATO nations for provoking Putin's war on Ukraine by ignoring Putin's view that for Ukraine to become "pro-America liberal democracy" would be an "existential threat" to Russia.

Despite its shocking incompatibility with the "rules-based international order" established by 150 years of treaties rooted in just war theory and natural law, Mearsheimer's view is popular because it claims to be brutally honest about "harder, darker constraints of an anarchic world," which follow from a few postulates about sovereign states and their leaders' motives.

But in fact, the spell it casts on thinking about foreign policy is deeply misleading for three main reasons, ranging from more to less obvious.

First, offensive realism is not merely an empirical or predictive device, as its defenders sometimes like to claim: It tells leading nations like the United States to allow other powerful states a limited "sphere" in which they act as hegemons, but also to "counterbalance" them when, like China today, they threaten interests beyond their own immediate region.

This is an imperialist standpoint typical of 19th-century thinking, as Mearsheimer readily admits: It tolerates, and thus encourages, the poisonous notion that a nation's great power permits it to turn otherwise-independent states around it into mere proxies and use their peoples as "buffers" against conceivable foreign attacks.

For example, in 2016, Mearsheimer and coauthor Stephen Walt wrote in Foreign Affairs that what "really matters" most for the United States is to preserve "U.S. dominance in the Western Hemisphere" while weakening other potential hegemons. They recommended leaving Syria to Putin, despite the Russian forces targeting thousands of civilian buildings and hundreds of hospitals during its air campaign in Syria.

Advertisement

This view, which once countenanced American attempts to control regimes in Latin America, has been rejected by popes at least since Populorum Progressio in 1967, and by the U.S. government since the late 1980s. As Adam Tooze explains, offensive realism traces back to the Nazi lawyer Carl Schmitt's belief in "a world order based on dividing the planet into large spatial blocs, each dominated by a major power."

The moral idea that legitimate sovereignty depends on protecting human rights, or the common good more broadly understood, which underwrote the U.N.'s "responsibility to protect" doctrine, has no place in this framework.

Second, while Mearsheimer has been lauded for "predicting" the war in Ukraine, he got Putin's motives mostly wrong. Putin knows that NATO is a defensive alliance that has no plans or desire whatsoever to invade Russia. Kremlin experts understood that NATO admitted Eastern European nations only to secure them against any return to the horrors they suffered under the totalitarian fist of the Soviet Union — fears that have now been fully justified.

Two decades ago, Putin even wanted Russia itself to join NATO; this tragically wasted opportunity runs contrary to offensive realism theory. Instead, as Robert Person and Michael McFaul argue, what Putin feared was never NATO expansion but rather the spread of democratic values. Kremlin complaints about NATO were correlated with upsurges of democratic reform movements within Russia inspired by the Arab Spring in 2011 and later by Ukrainians ousting Putin's puppet ruler in Kyiv.

Russian President Vladimir Putin delivers a speech during a meeting with graduates of the country's higher military schools at the Kremlin in Moscow June 21. (AP/Kremlin Pool Photo via AP/Sputnik/Kirill Kallinikov)

In sum, Putin sees that the main threat to his kleptocratic dictatorship is not NATO forces within his geographic region, but rather ideals of democratic self-governance and global standards that clamp down on corruption. Add to this, as Ross Douthat notes, following Anne Applebaum, Putin's "very personal desire to restore a mystical vision of a greater Russia."

More generally, as Applebaum and Garry Kasparov argue, the dictators in Russia, China, North Korea, Belarus, Iran and Nicaragua "understand that the language of democracy, anti-corruption, and justice is dangerous to their form of autocratic power."

Offensive realism theory massively understates the influence of such big ideas that move hearts and minds. It would have us believe that governments should focus only on material wealth and physical protection of territory. Political leaders' motives in foreign relations are more complex than this naive deterministic picture implies.

For example, Chinese leaders fear uncensored Hollywood movies as much as they fear insecure supply chains for food and raw materials, which they are shoring up through increasing their influence in Africa. Their terror that "Western" ideals — they mean individual autonomy and independent thought — will harm Chinese "interests" has more in common with Taliban religious dogma than with military or economic strategy.

This ambiguity about "national interests" explains why offensive realism theory offers no clear criteria to delimit a great power's "natural" sphere within which we should recognize its suzerainty. For example, are small islands near the Philippines in China's putative sphere, despite an international tribunal's ruling against Beijing's claim?

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskyy addresses leaders via a video screen during a roundtable meeting at a NATO summit in Madrid June 29. (AP/Manu Fernandez)

Similarly, in 2014, one could have invoked Mearsheimer's own power-balancing rationale to argue for admitting Ukraine into NATO as a way to "contain" Russia's rising power not only in Belarus but also in Syria, Iran, Libya and Mali, which are far from any romanticized ancient Slavic empire.

Third, the strategic axioms on which offensive realism is based only remain plausible while not enough world leaders believe in a rules-based order founded on the common goods of humanity. Thus, offensive realism helps foster and maintain the very attitudes of distrust and expectations of success through conquest that force peoples who only want peace and prosperity instead to adopt a war footing.

In other words, offensive realism's attraction is like the proverbial emperor's new clothes: It is a partly self-fulfilling prophecy that would predict little in a world where a global alliance of even moderately just republics established trust in minimum thresholds of decency for all governments.

Therein lies the saddest irony. Mearsheimer's influential dogma, which has even gained a hearing in Rome, is helping to preserve precisely the global anarchy and cynicism that it takes as starting postulates. Offensive realism theory may have emboldened Putin and motivated some European leaders to resist admitting Ukraine into NATO when that could have saved its people from ruin.

People display a Ukrainian flag as Pope Francis delivers the traditional "urbi et orbi" ("to the city and the world") blessing at the end of the Easter Sunday Mass he led in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican April 17. (AP/Alessandra Tarantino)

These liabilities reveal the extreme opposition between offensive realism theory and Francis' calls for a global system in which nations cooperate to reduce poverty, stop environmental destruction, and prevent new arms races that waste trillions of dollars.

In an interview concerning his 2021 book, God and the World to Come, the Holy Father said, "We can heal injustice by building a new world order based on solidarity." By denying that such ideas can inspire a world with less war and arms trafficking, Mearsheimer and his allies perpetuate a self-fulfilling kind of despair masquerading as tough strategic wisdom. They have even said that we should have kept a billion Chinese people in lethal poverty as long as possible in order to check China's rise to power.

With respect to offensive realism theory, there are viable ways to end aggressive wars and mass atrocities without promoting poverty for strategic gain. As I have argued, the path begins with extending the G7 group of nations to include South Korea, Australia and eventually India, Indonesia and Brazil, thereby turning the G7 into "Democratic 10+."

Such an expanded group should become the core of an alliance broader than NATO, which can meet rising threats, enforce minimum standards worldwide, and reduce corruption. This would help fulfill Catholic social teaching. Christians of all denominations should support a global order in which Mearsheimer's theory is regarded as merely an archaic historical artifact.