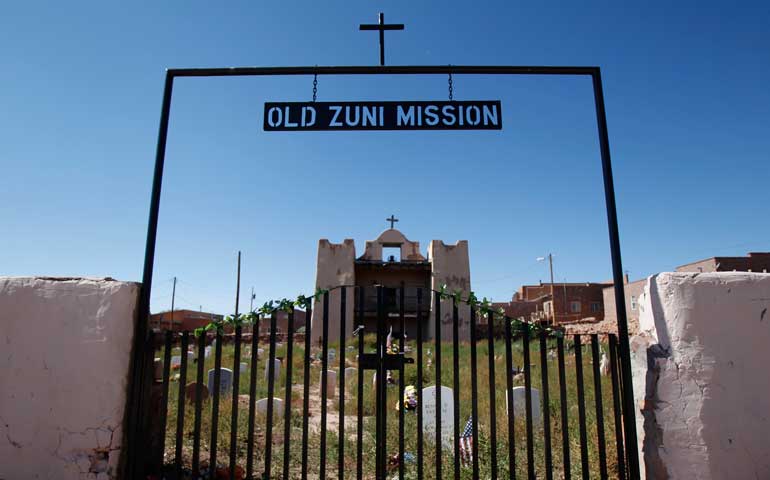

A sign frames the Old Zuni Mission on the Zuni Pueblo Indian reservation in New Mexico. (CNS photos/Bob Roller)

The year 2015 was meant to be a joyous one for the Gallup diocese. It marks the 75th anniversary of the founding of the diocese, and normally that would be a cause of celebration in parishes and schools across New Mexico and Arizona.

However, celebrations have proven to be few and subdued as the diocese continues to be mired in bankruptcy court, and the legacy of clergy sex abuse continues to cast a long shadow across the diocese.

Although Bishop James Wall designated Dec. 12, the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, as the kickoff date for the yearlong anniversary celebration, the event was marked with just a low-key Friday morning Mass at Gallup's Sacred Heart Cathedral.

In contrast, three days later, the bishop made national news when he publicly released an updated list of credibly accused sex abusers from the diocese. The list, which included the names of 30 diocesan and religious order priests and one lay religious education teacher, was also posted on the diocesan website for the first time.

"The publication of these additional names does not mean that our vigilance and continued investigation ends here," Wall said in his statement. "The investigations remain ongoing."

Inexplicably, however, the list failed to include the names of four former Gallup priests who had previously been identified as abusers by other Catholic dioceses or religious orders. When the Phoenix diocese was founded -- where Wall once served as vicar of priests -- it inherited two of the clergy abusers from Gallup.

There has also been the unwanted public drama surrounding an AWOL international priest. In early October, officials with the Gallup diocese were caught flatfooted when a visiting priest abruptly "abandoned his assignment," without notifying the diocese or requesting permission for a leave of absence. Fr. Ravi Kiran, a member of the Heralds of the Good News from India, left St. Anthony Mission, a small Native American parish and school on the Pueblo of Zuni, in the midst of a diocesan audit of his mission.

Well-liked by many of the 100-plus parishioners who regularly attend St. Anthony, Kiran was nevertheless a divisive figure to about a dozen parishioners who had left, claiming that Kiran had pushed them out of their own church. In the wake of the priest's departure, allegations began to surface regarding possible mismanagement of church funds, particularly related to his extensive renovation projects around the mission.

Other than releasing their initial statement, diocesan officials have not responded to repeated media questions about the priest's departure or his financial management of the mission. Instead, various officials have made conflicting statements.

On Dec. 7, Fr. Kevin Finnegan, diocesan chancellor and vicar general, told St. Anthony parishioners that Kiran had been cleared of wrongdoing. Later that week, however, both Susan Boswell, the diocese's lead bankruptcy attorney, and Suzanne Hammons, diocesan spokeswoman, insisted the investigation was ongoing.

Hammons has since repeatedly promised a public release of an audit summary, but five months after Kiran's disappearance that has yet to happen.

Meanwhile, Kiran, who is presumably back in India, has claimed in recent emails to the media that not just one, but two audits have cleared him of wrongdoing. Diocesan officials remain silent on the subject.

Kiran's former reservation parish in Zuni, which he said had about $4 million in investment accounts when he arrived, may have had a healthier bank account than the bishop's chancery 40 miles away.

While Kiran was in the middle of a nearly $2 million renovation program, the Gallup bishop was borrowing $200,000 from the Phoenix diocese and $29,000 from the Santa Fe, N.M., archdiocese to prepare for Gallup's Chapter 11 filing in U.S. Bankruptcy Court.

Now, more than a year after the bankruptcy filing, Gallup's post-petition professional fees for attorneys, accountants and insurance investigators are up to more than $1.8 million.

So how will the Gallup diocese eventually fund its plan of reorganization? According to court documents, the diocese is looking to three primary sources: insurance money; contributions by other Catholic dioceses and religious orders that allegedly allowed their sexually abusive clergy to serve in the Gallup diocese; and the sale of real estate.

The diocese has entered into court-approved agreements with some insurance companies and with the Franciscan Province of St. John the Baptist in Cincinnati to share confidential information with the presumed goal of reaching monetary contribution agreements. However, attorneys for the Corpus Christi, Texas, diocese and the Franciscan Province of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Albuquerque, N.M., have proved less cooperative thus far.

Although the diocese's bankruptcy attorneys initially promised to consider selling "property that is not critical to the continued mission and ministry" of the diocese, they startled local Catholics in January when they asked U.S. Bankruptcy Judge David Thuma to authorize the hiring of an appraiser to determine the value of five key church properties.

Three of the properties -- the chancery, Sacred Heart Retreat Center and Sacred Heart School -- are located in Gallup and are tied to the mission and ministry of the diocese. There is speculation that the diocese may have the Catholic Peoples Foundation and the Southwest Indian Foundation, its own nonprofit organizations that it claims are separate entities, purchase the properties from the diocese to help fund the reorganization plan.

The other two properties slated to be appraised are in Thoreau, N.M.: St. Bonaventure Indian Mission, which educates about 200 mostly Native American students, and additional property believed to belong to the mission. In a dispute simmering quietly on the bankruptcy backburner, an attorney for the mission has already claimed the property belongs to St. Bonaventure, while attorneys for the diocese have listed it as diocesan property.

While that potentially explosive dispute has yet to be resolved, the bankruptcy judge recently approved the employment of the appraiser scheduled to assess the St. Bonaventure property.

Meanwhile, about 90 pieces of diocesan-owned commercial property, residential lots, and ranchland in Arizona and New Mexico -- with no discernible tie to the mission and ministry of the diocese -- have not been listed for appraisal.

[Freelance reporter Elizabeth Hardin-Burrola has been covering the Gallup diocese for 13 years.]