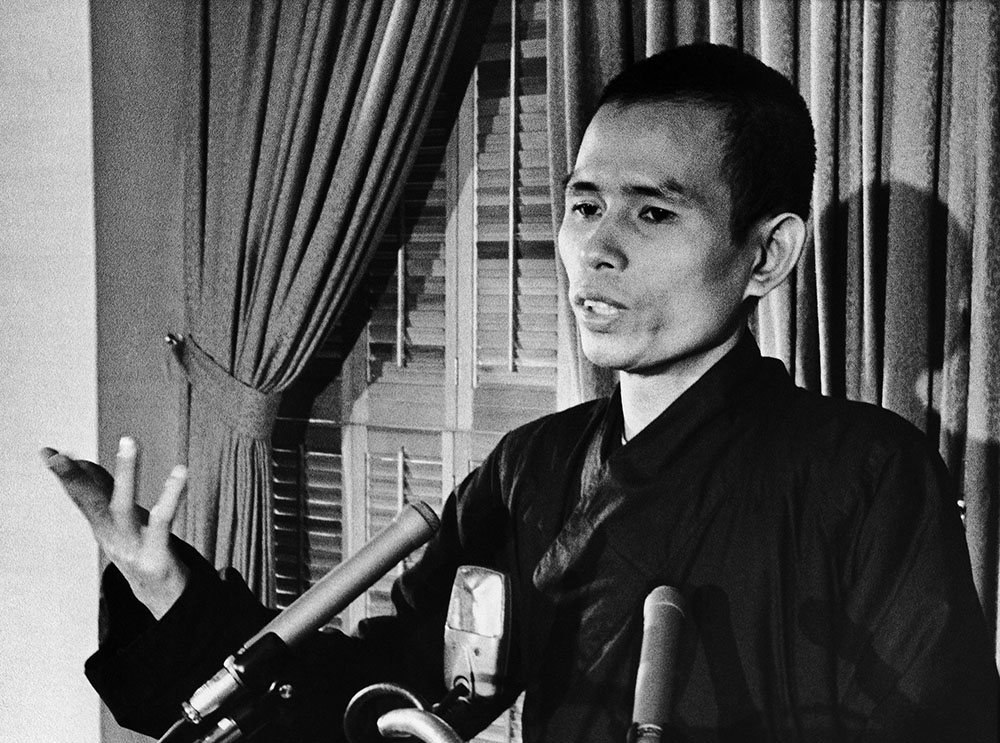

Thích Nhất Hạnh speaks at a news conference in Washington, D.C., on June 3, 1966. (AP/Washington Star)

Editor's note: Thích Nhất Hạnh, the Vietnamese monk who popularized mindfulness in the West and whose vast peace writings introduced countless people to Buddhist ideas and practices, died Jan. 22, 2022, at the age of 95 at Từ Hiếu Pagoda, the Buddhist temple in Hue, Vietnam.

It was in May 1968, while returning from Vietnam after two years of civilian voluntary work, I met Thích Nhất Hạnh for the first time. That meeting came in Paris as the Vietnam peace talks were just getting underway. Nhất Hạnh was in Paris as the head of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation.

We spent an afternoon together discussing the war and fragile peace efforts. My most lasting impression was his gentle demeanor. He offered me tea and spoke in a quiet voice, his eyes sharp and focused, his smile timid, almost shy.

The Paris Peace Accords, formally ending U.S. and North Vietnamese hostilities, were eventually signed in 1973.

In May 1993, preparing a feature article for NCR, I spent a week participating in a retreat at Plum Village, the monastery Nhất Hạnh founded in France. The village then consisted of a half dozen 19th-century stone farmhouses converted into dormitories, with kitchens, dining rooms and several meditation centers: large, open rooms with glass windows and wooden floors adorned with cloth cushions and straw mats.

We would eat our meals in silence, chewing each morsel of food from our vegetarian plates 50 times before swallowing. We would take slow and deliberate "meditation" walks, conscious of our breathing with each step we took. If a bell, any bell, sounded in the distance, we would stop anything we were doing to pause and reflect for one minute.

One afternoon, Nhất Hạnh invited me into his small dwelling, a one-room wooden structure on the side of a hill overlooking a green meadow. It was new at the time. The room was barren except for a coffee table, behind which he sat in a lotus position. I sat on the floor in front of him.

He greeted me with a smile, inviting me to sit closer, next to him at the table. On the table sat an old scratched thermos and two small cups with saucers beneath them. He poured tea and soon asked a question.

Advertisement

"How are Vietnamese refugees faring in the United States?" he wanted to know.

I answered that Vietnamese people in the United States generally have a reputation for being industrious and most have found gainful employment.

But that apparently was not precisely what he was asking. He said he wanted to know how they were handling their separation from their homeland. He wanted to know about the young. He said he had heard many young were estranged from their parents and some had even joined gangs for mutual support.

Additionally, he wanted to know what the Catholic church was doing to reach the alienated young. "What authentic Catholic teaching," he asked, was speaking to the alienated young?

He went on, saying that all church leaders need to work harder to reach the young. He said it was his impression that material things, like designer clothes and fast music, were meeting needs not being met by religious teachers.

He added that Buddhism is not the answer to what the American young are searching for. That answer, he said, must come from within Western traditions. At best, Buddhism, he said, can only help point a way.

He stressed that Catholic leaders, including Catholic journalists, need to search Catholic tradition for "authentic teachings" capable of reaching the young. "It must be authentic to be heard," he said, adding that by authentic he means teachings grounded in "true understanding and true love."

We spoke of Vietnam and I asked if he would like to return. He said he had never stopped wanting to return but had grown to realize he continues to have followers in France. He added: "I am here; I am in Vietnam."

That afternoon, as he sat there with teacup in hand, I looked into his brown eyes. I remember thinking he was truly at peace, fully tranquil, and wondering if I could ever be similarly peaceful — or wondering if it were something I really sought.