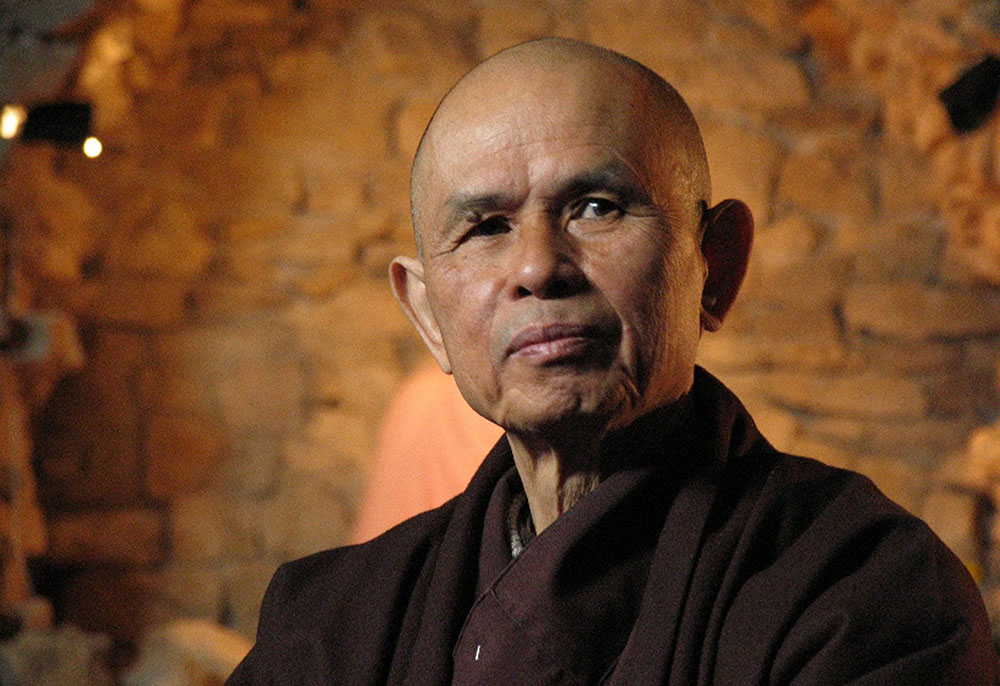

Thích Nhất Hạnh is seen in a 2007 Paulist Pictures documentary, "The Big Question." (CNS/Courtesy of Paulist Productions)

Thích Nhất Hạnh, the Vietnamese monk who popularized mindfulness in the West and whose vast peace writings introduced countless people to Buddhist ideas and practices, died Jan. 22, 2022, at the age of 95 at Từ Hiếu Pagoda, the Buddhist temple in Hue, Vietnam, where he entered monastic life at the age of 16 and returned to prepare for his death in 2019.

Forced into exile in the 1960s, he lived and taught overseas for more than five decades, speaking out for nonviolence as a way of life while teaching his mindfulness meditation practices.

Nhất Hạnh (he was known as "Thầy" to his followers) was said to have been the second best known Buddhist teacher in the contemporary world after the Dalai Lama. (Thích is an honorific and is Vietnamese for Sakya, which is the Buddha's family name.)

Martin Luther King Jr. considered Nhất Hạnh a friend and nominated him for the 1967 Nobel Peace Prize. Years later, Oprah Winfrey interviewed him, saying he had deeply influenced her thinking.

Fr. Peter Phan, who holds the Ellacuria Chair of Catholic Social Thought at Georgetown University and is also a Vietnam native, said he is grateful for the monk's peace and justice work and for his spiritual guidance to millions of persons of different religious traditions. Phan added that Nhất Hạnh's teachings and writings will ever remain a fountain of wisdom and insight not only for the common people, but also for religious scholars and theologians of all faiths.

Thích Nhất Hạnh in Vietnam in 2007 (Flickr/d nelson)

Nhất Hạnh published more than 100 books in English, ranging from manuals on meditation, mindfulness and engaged Buddhism, to poems, children's stories and commentaries on ancient Buddhist texts, exposing the West to new Eastern meditation practices.

Among his most popular books have been The Miracle of Mindfulness; Living Buddha, Living Christ; Being Peace; and Peace Is Every Breath. Winfrey, in a May 2013 interview with Nhất Hạnh, confessed she kept a copy of Living Buddha, Living Christ at her bedside.

Exiled from Vietnam during the war, Nhất Hạnh spent the last half century in France, but traveled throughout the globe, holding retreats and mindfulness workshops.

Nhất Hạnh's mindfulness taught that one generates energy when bringing the mind back to the body, getting in touch with the present moment. It requires breath awareness and focusing on what is going on around you. Through this focusing and by slowing down one's state of mind, awareness is deepened and healing takes place.

He invited practitioners to employ mindfulness throughout the day, while doing the simplest of tasks: brushing one's teeth, washing dishes, walking, eating, speaking or listening. Mindful eating might require chewing each morsel of food for a minute or more, focusing on the source of the food and the meaning of the act.

Nhất Hạnh wrote that the moment when one goes back to one's breath and breathes mindfully, holiness is there, because mindfulness is the substance of holiness. In that moment, one touches God because the Holy Spirit is there at the same time.

Born in 1926, Nhất Hạnh discovered Buddhism at an early age. He once said he first became interested in Buddhism at the age of 7 or 8 when he saw a picture of Buddha. From then on, he felt called to be a monk and entered the Từ Hiếu temple in Hue in 1942.

Từ Hiếu Pagoda in Hue, Vietnam (Dreamstime/Donguyenbc)

As a young monk in the 1950s, he became actively engaged in the movement to renew Vietnamese Buddhism. He studied at a secular university in Saigon, and was one of the first monks to ride a bicycle.

In 1961, Nhất Hạnh traveled to the U.S., where he studied comparative religions at Princeton University and was subsequently appointed lecturer in Buddhism at Columbia University.

Returning to Vietnam two years later, he formed the School of Youth for Social Service. It was viewed as revolutionary at the time, as it combined traditional Buddhist practices with service in society. Mindfulness played a role as well as a means to building a better world. Followers believed it enhanced compassion and provided energy to service the common good.

A few years later, Nhất Hạnh's renewed Buddhism practice took on the name "engaged Buddhism," a term coined in his 1967 book, "Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire."

Engaged Buddhism embraces 14 principles, including speaking truthfully and constructively; not using the Buddhist community for personal gain or profit; living with a vocation that harms neither humans nor nature; and living in accord with the ideals of compassion, protection of life, and prevention of war.

It was in 1965, when the South Vietnam government of Ngô Đình Diệm began to put down Buddhist protests in Central Vietnam, that Nhất Hạnh began to run afoul of the Saigon government. In late 1966, Nhất Hạnh and his students were among the protesters signing a document calling for national reconciliation. "It is time for North and South Vietnam to find a way to stop the war and help all Vietnamese people live peacefully and with mutual respect," the statement read.

Advertisement

Nhất Hạnh was denounced by the Saigon government and was described as a communist sympathizer.

That tarring would affect his image, especially among Vietnamese anti-communists, both in Vietnam and in the U.S., through the rest of his life.

As anti-war activities grew in the U.S. and news of Nhất Hạnh's peace activities spread beyond Vietnam, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, an umbrella group of nonviolent organizations dating to the mid-1930s, invited him in 1966 to visit the U.S.

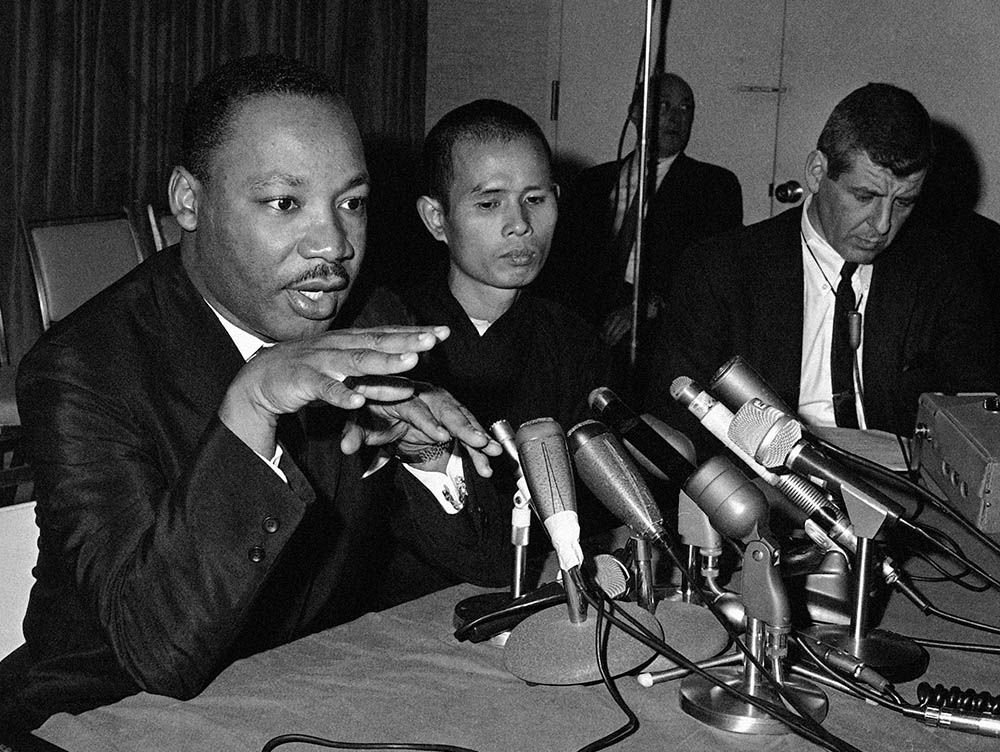

That trip would be historic, as during it Nhất Hạnh first encountered both Martin Luther King and Trappist monk Thomas Merton. The three men bonded in their pursuits of peace and nonviolence. Those encounters, while short-lived, were influential.

King, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate in 1964, was influenced by Nhất Hạnh, and on Jan. 25, 1967, wrote a letter to the Nobel committee nominating Nhất Hạnh for the peace prize.

He wrote: "I do not know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Prize than this gentle Buddhist monk from Vietnam. ... [He] offers a way out of this nightmare, a solution acceptable to rational leaders. ... His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a momentum to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity."

Nhất Hạnh met King in May 1966 in Chicago, where the monk encouraged the civil rights organizer to extend his call for racial justice and nonviolence to the villages of Vietnam. Following that meeting, with Nhất Hạnh at his side, King for the first time publicly expressed his opposition to the war in Vietnam.

It was an address the next year, speaking at Riverside Church on April 4, 1967, in New York City, King boldly expressed his opposition to the Vietnam War, citing Buddhist opposition to the American involvement.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (left), in a Chicago news conference with Thích Nhất Hạnh (center), calls for a halt in bombing of Vietnam on May 31, 1966. (AP/Edward Kitch)

During his 1966 trip to the U.S., Nhất Hạnh also traveled to Kentucky, where he met Merton at the Abbey of Gethsemani, near Louisville. The monks found immediate mutual sympathy. After the visit, Merton told his students, "Just the way he opens the door and enters a room demonstrates his understanding. He is a true monk."

At the time, interreligious dialogue was a relatively new development, making Merton's remarks all the more notable.

Indeed, this monk-to-monk dialogue represented an early breakthrough in interreligious dialogue. The Second Vatican Council had recently issued one of its major documents, Nostra Aetate, calling for such dialogue. The Nhất Hạnh-Merton bonds were further cemented in an essay Merton wrote for Jubilee magazine, published in August 1966 and titled "Nhất Hạnh Is My Brother."

Wrote Merton, in words that shocked some Catholics at the time: "I have far more in common with Nhất Hạnh than I have with many Americans, and I do not hesitate to say it. It is vitally important that such bonds be admitted. They are the bonds of a new solidarity ... which is beginning to be evident on all five continents and which cuts across all political, religious and cultural lines to unite young men and women in every country in something that is more concrete than an ideal and more alive than a program."

After leaving the United States, Nhất Hạnh returned to Europe, where he had an audience with Pope Paul VI. The two religious figures urged greater cooperation between Catholics and Buddhists to help bring about world peace, starting with ending the conflict in Vietnam.

This proved too much for the regime in Saigon, which viewed pacifism as tantamount to collaboration with the communists. It prevented him from returning. The next time the monk would be allowed to visit Vietnam was in 2005.

As Nhất Hạnh settled into a new phase of life, in exile in France, he focused on his writings — and they began to spread. In 1975, a long letter he had written to a monk in Vietnam on the practice of mindfulness was translated into English and published under the title of The Miracle of Mindfulness. It was a major breakthrough and the result of a collaboration with Mobi Ho, who diligently worked with Nhất Hạnh, line by line, as translator.

The manuscript was eventually translated into many languages. It was to be an introduction to the West of Nhất Hạnh's characteristically simple and lyrical prose.

A view of the grounds of Plum Village in France (Flickr/Geoff Livingston)

It was then Nhất Hạnh founded his international retreat center, called Plum Village, near Bordeaux in southwest France, his first Western monastic community. For decades, that would be his new home.

Occasionally, he would trek the globe holding mindfulness retreats. These included several visits to the United States where his mindfulness practices began to take hold.

In 2005, Nhất Hạnh, whose influence stretched the globe, finally gained permission from the Vietnamese communist government in Hanoi to return to his native land for a visit. He was allowed to teach there briefly as well as travel the country with monastic and lay members from his root temple in Hue.

The trip was not without controversy. Some prominent Vietnamese monks called for Nhất Hạnh to make a statement against the Vietnam government's poor record on religious freedom. He did not.

Nhất Hạnh returned a second time to Vietnam in 2007, and yet again in 2008. The Unified Buddhist Church called Nhất Hạnh's visits a betrayal, symbolizing his willingness to work with his coreligionists' oppressors. His supporters defended the visit, saying its purpose was to support Buddhism and heal wounds left over from the Vietnam War.

In recent years, the monk also took up the cause of the fragile state of our planet, issuing calls for personal transformation needed to address the ecological crisis.

The truth of impermanence, he wrote, applies to all things, including civilizations — including our own. The peace that comes with accepting this truth will bring the possibility of hope: "With this kind of peace we can make use of the technology that is available to us to save this planet of ours. With fear and despair, we're not going to be able to save our planet, even if we have the technology to do it."

In November 2014, a month after his 88th birthday, and following several months of rapidly declining health, Nhất Hạnh experienced a severe stroke in a hospital in Bordeaux, France, losing his ability to speak and becoming mostly paralyzed on the right side. He was flown to the University of California San Francisco Hospital for treatment and recovery, eventually returning to France.

In November 2019, he left France for the last time, stopping in Thailand before flying home to Hue to live out his last days.