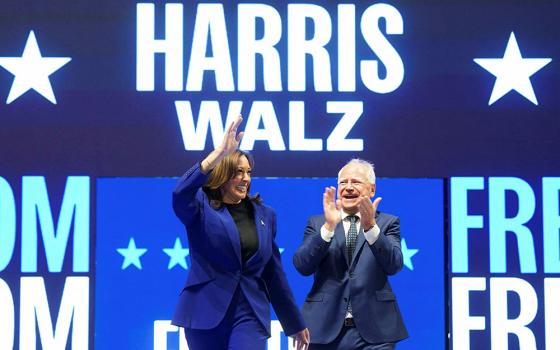

Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-California, is seen in Washington Sept. 7. (CNS/Joshua Roberts, Reuters)

The confirmation hearing for Notre Dame Law Professor Amy Coney Barrett caused quite a stir after some Democratic senators asked her questions about her Catholicism. Archbishop William Lori, chair of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' Committee on Religious Liberty issued a statement that fretted, "Were the comments of the Senators meant as a warning shot to future law students and attorneys, that they should never discuss their faith in a public forum, if they have aspirations to serve in the federal judiciary? In truth, we should be encouraging faithful, ethical attorneys to serve in public office, not discouraging them by subjecting them to inappropriate, unnecessary interrogation based on their religious beliefs."

You would think we were only a step away from a Know Nothing riot!

Let's stipulate that the comments from Sen. Dianne Feinstein and Sen. Dick Durbin were irregular. "When you read your speeches, the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you," Feinstein said. "And that's of concern when you come to big issues that large numbers of people have fought for for years in this country." Feinstein went on to say that, "Dogma and law are two different things. I think whatever a religion is, it has its own dogma. The law is totally different." Certainly, dogma and law are different, but one wishes the senator would explain how law and morality at least do intertwine in her worldview.

Durbin asked what might be an inappropriate question: "Do you consider yourself an orthodox Catholic?" But he prefaced his question by noting that some who style themselves "orthodox Catholics" use the designation to distance themselves from, and cast aspersions upon, their co-religionists. He added, "There are many people who might characterize themselves orthodox Catholics who would now question whether Pope Francis is an orthodox Catholic. I happen to think he's a pretty good Catholic." Then he posed the question. Durbin has no doubt been on the receiving end of challenges to his orthodoxy. He was just engaging in payback.

At America magazine, Barrett's colleague at Notre Dame Law, Rick Garnett, said, "I don't like to speculate about motivations, but it seems clear to me that the remarks from both of those senators reflected the view that a Catholic nominee for the federal bench is of special concern because the senators are bringing certain presumptions that a Catholic jurist won't follow the law. That assumption is unfortunate and reflects some sort of prejudice."

Advertisement

But another former colleague, Boston College Professor (of both law and theology) Cathleen Kaveny, had a different take on the line of questioning. "You can't say that our faith on the one hand has ramifications for politics, law and the common good and on the other hand expect not to answer questions about it and claim that faith is purely private," Kaveny said.

The responses are telling. Both Lori and Garnett evidenced the defensive posture that is so indicative of the cultural warrior style. They completely miss what is to me the most obvious fact about the controversy: There is a big, fat compliment to Catholics in this. It is unimaginable that a senator would pursue a similar line of questioning with a Presbyterian or a Congregationalist. Not because there are no devout, even fervent, members of those denominations. But Catholicism not only is assumed to matter, but matter as an intellectual force, one that does not fit easily within other, and arguably more pronounced, currents of opinion in our culture. That not-fitting-in is a sign of vitality because a religion that has lost the ability to critique its culture is a religion that is dying or dead.

Secondly, on the question of whether the questions and comments were appropriate or legitimate, I think Kaveny has the better of the argument. The same people who are now criticizing the senators, such as Archbishop Charles Chaput, have been advocating for Catholics to bring their faith into the public square and criticizing those they perceive as checking that faith at the door. Barrett did not use her hearing to witness to the faith. She said it would not matter to her decisions as a judge. Alas, she gets a pass from the right field bleachers.

Which leads to another conclusion: Barrett missed a great opportunity to skewer her interrogators. Her mission was to get through the hearing. But she would have demonstrated the kind of cleverness we want in a judge if she had replied, "Sen. Feinstein, if I were the kind of legal scholar whose jurisprudence was of a kind you approve, I think your question would be legitimate. But I am an originalist, and it is not my beliefs that will enter into my opinions but the beliefs of the founding fathers. The liberal judges of whom you approve, they are the ones who need to explain whence they derive their first principles, be it from John Rawls or Thomas Aquinas." Of course, originalism is a dogma, too, one I find unconvincing, but it would have been a fun moment to watch if she had managed that kind of fighting reply.

There is one other line of questioning, this one directed at the senators, that warrants some examination. Some, such as the Catholic League's Bill Donohue, suggested we were back in 19th century anti-Catholic sensibilities and that no senator would ever ask a Muslim nominee how the Quran might influence their jurisprudence. Others, like Sohrab Ahmari in the New York Times also compared the questioning of Barrett to prejudice against Muslims.

In a strictly formal sense, asking "Are you an orthodox Muslim?" is the same question as "Are you an orthodox Catholic?" And no difference between posing the latter question to a Catholic today or to a 19th-century Catholic. But there is a large real difference. Catholics in the 19th century, like Muslims today, were a persecuted minority. Today, we RCs are the largest denomination in the country, and white Catholics are the most affluent Christians in the land. A concern about prejudice against the weak is fundamentally different from a bias against a powerful group. I will never stop laughing at WASP jokes, and you shouldn't either.

The bigger problem with this confirmation hearing, like all of them, is that they are a farce. The only legitimate reason to refuse to confirm a judge is if they were caught smoking pot or unwittingly employing an undocumented immigrant or cribbing someone else's writings. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse put his finger on it at this same hearing. "We sit here in this bizarre-o world in which we're asked to pretend that nominees' personal views and social views have no role, and we shouldn't discuss them at all, and we're all just going to sit around following precedent," he said. "The protocol for answering questions that has developed in this committee makes the committee look preposterous. It makes the nominees look preposterous."

And let the church, and the Senate, say "Amen."

I just looked out my window and there are no anti-popery placards outside my house. No one is burning an effigy of the pope. Amy Coney Barrett will be confirmed. Law and morality will continue to intertwine in ways that are worth probing, even at a confirmation hearing. And the church will last until the end of time. Relax.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest! Sign up to receive free newsletters, and we will notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.