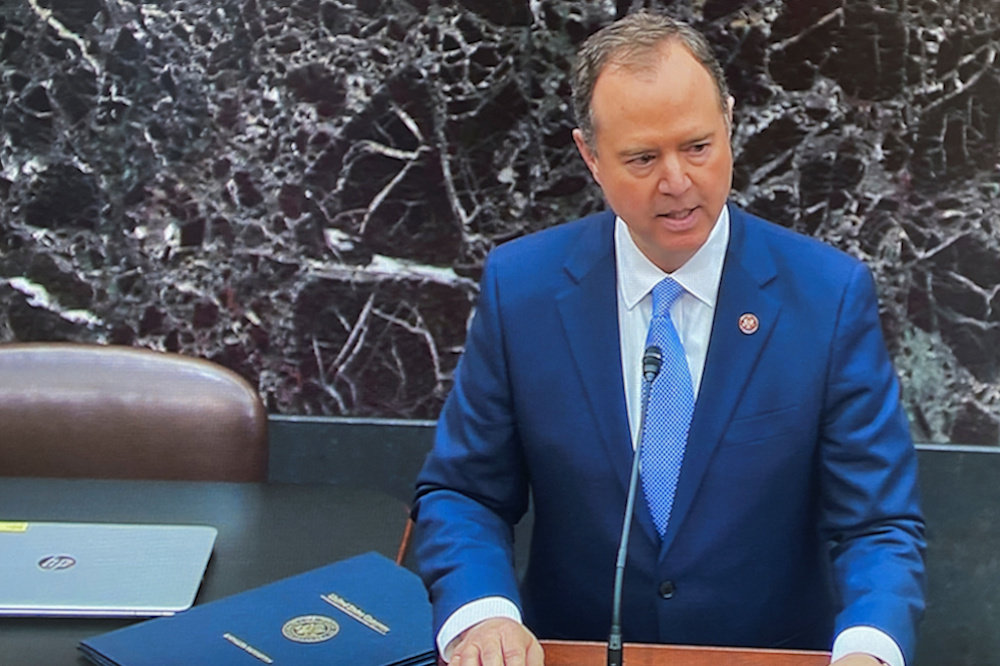

Rep. Adam Schiff (D-California) chairman of the House Intelligence Committee and lead impeachment manager for the House, reads the House articles of impeachment of President Donald Trump on the floor of the U.S. Senate Jan. 16 during the procedural start of the Senate impeachment trial. (CNS/U.S. Senate TV handout via Reuters)

I have never met Aaron Blake, who writes "The Fix" column at The Washington Post, but sometimes I wonder if we were separated at birth. In the course of the day, I will be thinking about what the focus of my next column will be, what the main outline of the argument should be, what is the lede, the sort of questions you need to have largely resolved before you sit down at the computer to start writing. Before writing, I may scan the papers to see if any major news broke in the afternoon that requires more immediate attention. And, I will come across an article by Blake that addresses the very same thing I wanted to address, and sometimes with the same lede!

So it was Wednesday evening during the first day of questions in the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump. Here is Blake's original lede, now changed: "The world's greatest deliberative body hasn't exactly lived up to its billing thus far in Wednesday's Senate impeachment trial proceedings." Ya think? It was bizarre watching Senate pages bring scraps of paper up to the dais so that the chief justice could read the questions, drafted by senators and posed to either the president's defense team or the House managers. There is no public debate and that lack is not unique to the trial: Senators no longer debate in any meaningful sense of the word. There is no one in the Senate today capable of delivering a speech akin to Daniel Webster's "Second Reply to Hayne." No one. There is no deliberation anymore outside the Majority Leader's office.

Blake's column, which he is continually updating, is, as of this writing, up to six of the most interesting questions of the day. The first asked how senators should vote "if they deduce that Trump had both official and personal motives for his actions regarding Ukraine." The fact that the question was posed by Sens. Susan Collins (R-Maine), Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) and Mitt Romney (R-Utah) shows, as Blake notes, that they are looking for an off-ramp, a rational for voting to acquit the president.

The question is nicer than it might seem at first blush, and one of the president's attorneys, Patrick Philbin, rightly noted that all politicians have their re-election in prospect when they make decisions. Our constitutional system presumes self-interest to be one of the bulwarks against tyranny. In the case of the president's phone conversation with President Volodymyr Zelensky, however, there was no "official motive" for his request to investigate Hunter Biden, the son of the former Vice President Joe Biden. If there was, they would not have needed to send the president's private attorney, Rudy Giuliani, to conduct the pressure campaign.

The response from Trump attorney Alan Dershowitz made me think the professor is no longer at the top of his game. "If a president does something which he believes will help him get elected in the public interest, that cannot be the kind of quid pro quo that results in impeachment." Richard Nixon thought it was in the public interest to defeat the Democrats in 1972, but that did not justify authorizing a break-in at Watergate. Perhaps the better analogy is a prospective one: Under Dershowitz's theory, there would be nothing wrong if, the day after he is acquitted, Trump calls Russian President Vladimir Putin and asks if he will start coordinating with the reelection campaign.

Another question Blake identifies has to do with the quid pro quo at the heart of that phone conversation with Zelensky, and whether or not quid pro quos are standard operating procedure in negotiations with foreign governments. Of course they are. We ask Mexico to do X in return for our government doing Y at Mexico's request. What is wrong here is that the ask was not to help the United States pursue some interest or affirm some value. It was to help smear Biden.

Rep. Adam Schiff (D-California) brought in a well-placed analogy, based on President Barack Obama's famous open mic moment with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, which some of the president's defenders have likened to Trump's chat with Zelensky:

President Obama on an open mic says to Medvedev: 'Hey, Medvedev, I know you don't want me to send this military money to Ukraine because they're fighting and killing your people. I want you to do me a favor, though. I want you to do an investigation of Mitt Romney, and I want you to announce you've found dirt on Mitt Romney. And if you're willing to do that, quid pro quo, I won't give Ukraine the money they need to fight you on the front line.' "

Schiff added: "Do any of us have any question that Barack Obama would be impeached for that kind of misconduct? Are we really ready to say that would be okay if Barack Obama asked Medvedev to investigate his opponent and would withhold money from an ally that it needed to defend itself to get an investigation of Mitt Romney? That's the parallel here."

Advertisement

Well done. But I would have also noted something else. If Trump was genuinely concerned about corruption on the part of Hunter Biden, he should have contacted the FBI, not a foreign government. He knew the FBI would say, "We can't do that. It is illegal." So, he got Giuliani on the case.

I do not agree with Blake that the question whether or not the president voiced concern about corruption by the Bidens in Ukraine came up before the former vice president announced his candidacy for 2020 was a very important question. The most interesting thing about the question was that it was posed by Collins and Murkowski. People ask me if I think Collins will ever break with Sen. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and the answer is no. She is like Lucy with the football, and the Democrats are Charlie Brown. At the last minute she always, always pulls the football away.

Sen. Joe Manchin (D- West Virginia) did the world a favor when he asked a question of the president's lawyers: "Even Mr. Dershowitz said in 1998 that an impeachable offense, quote, certainly doesn't have to be a crime, end quote," Manchin stated. He then asked: "What has happened in the past 22 years to change the original intent of the framers and the historic meaning of the term high crimes and misdemeanors?" This was the most polite way of calling someone a hypocrite I have ever witnessed.

There is plenty of hypocrisy on both sides regarding their different stances now and during the impeachment of Bill Clinton. The core difference is obvious: Clinton had an affair and lied about it. Anyone can do that. Only the president can withhold foreign aid in order to secure cooperation on an unrelated and personal matter. Clinton did not abuse his office. He lied under oath. Maybe he should have been removed from office because of that. If it had happened now, he would have been removed. But it was not an abuse of a public trust and impeachment exists precisely to address such abuses.

The president's attorneys, unlike the House managers, were often playing a shell game, answering a different question from the one asked. Toward the end of the night, the president's lawyers were asked about the legality of foreign interference in an election, and Philbin replied that if credible information comes from a foreign source, there is nothing illegal in publicizing it. That is not what happened in this case. The president made a request, the Ukrainians did not offer information, credible or otherwise.

For the president, the scariest prospect arose not from a question or an answer but from a ruling. Chief Justice John Roberts let it be known that he would not read a question that disclosed the name of the whistleblower. It is against the law to reveal such names and doing so would gut the whistleblower protection statues that Republicans used to love. If Roberts decides he wants to start making rulings in accordance with standard trial procedures, who will stop him? It is one thing to corral Collins, Murkowski and Romney into voting against a proposal from Minority Leader Chuck Schumer. Voting to overturn a ruling by the chief justice is an entirely different thing and senators like Cory Gardner (R-Colorado), who is on the ballot this November, might think twice before doing so.

We know how this saga will end. "Moscow Mitch" McConnell will bend the Senate to his will yet again and the president will be acquitted. The question is how much of a stain or stench the proceedings leave on those who vote to acquit and, even more, those who vote not to hear from witnesses. It might prove indelible.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.