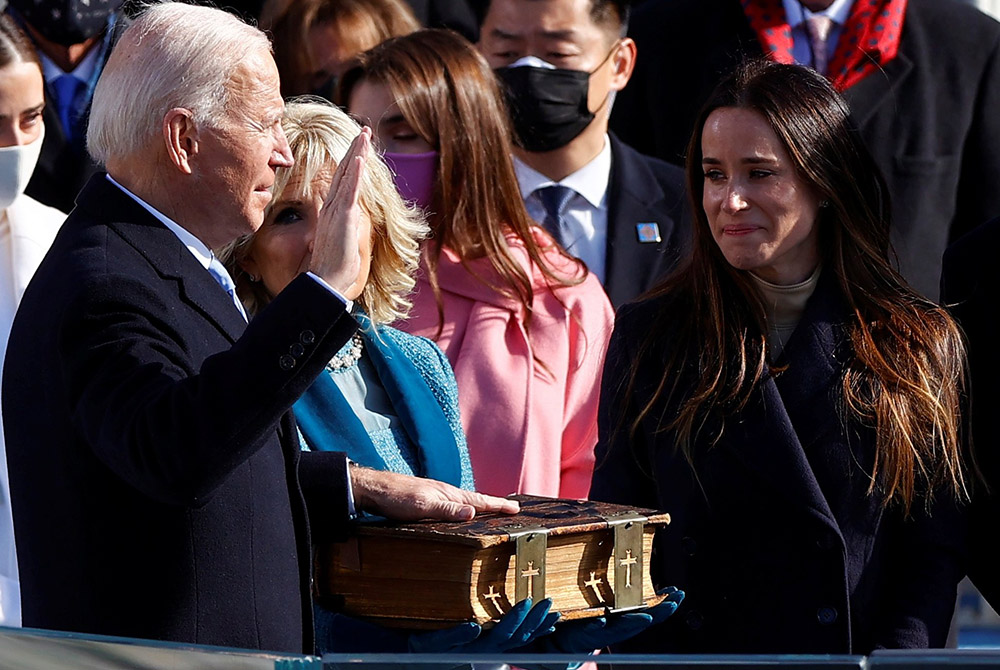

Joe Biden is sworn in as the 46th president of the United States by Chief Justice John Roberts as Biden's wife, Jill, holds the family Bible during his inauguration Jan. 20 at the Capitol in Washington. (CNS/Jim Bourg, Reuters)

Massimo Faggioli's new book Joe Biden and Catholicism in the United States comes just in time for those of us trying to make sense of the estuary where politics and religion meet in the U.S. at this moment in history. It is a moment in which so many foundational issues are implicated, a moment so pregnant with possibilities and so fraught with difficulties.

Faggioli's book explores those foundational issues with depth and insight. He is excellent in elucidating the immediate context of this hopeful moment when a Catholic president and a profoundly pastoral pope can make common cause on a variety of issues. "Relations between the United States and the Vatican clearly suffered during the Trump administration, a result of the undeniable incompatibility of the worldviews of Pope Francis and the 'Make America Great Again' president," he writes. "But equally obvious is the overlap that exists between support for Trump among practicing Christian voters (including many Catholics) and the attempt by influential sectors of the American Catholic Church to delegitimize Pope Francis both ecclesially and politically."

Nonetheless, he goes deeper. The heart of the book is an exploration of the fact that:

Both [Pope] Francis and Biden have the arduous task of exercising institutional leadership through a period of upheaval at all levels: environmental, economic, social, cultural and political. Their elections are both encouraging signs of the vitality of the institutional systems they lead. But it is not clear how much the institutional level can do to deal with the breaking of the balance at all other levels.

For both men, their task is both complicated and defined by the fact that the opposition to them tends to cohere in the same persons: The anti-Francis wing of the Catholic Church consists of the same cabal of the anti-Biden zealots who drafted or applauded the offensive Inauguration Day statement from the bishops' conference.

No theologian is better than Faggioli at explaining and critiquing the varieties of right-wing nuttiness that have flourished in the vineyard of American Catholicism the past 30 years. No one, so far as I know, has previously noted, as Faggioli does, that understanding the tensions between the arch-conservative Catholics who resist and resent Pope Francis and those Catholics, like the new president, who love him "must be understood in the context of the transition between two very different paradigms typical of conservative Catholic intellectual circles in the United States during the last decade. It is the transition from the Catholic neoconservative movement of the 1980s and 90s to an upheaval of revolt and ressentiment closer to anti-Vatican II traditionalism than to a legitimate cultural and theological critique of some aspects of the post-Vatican II period."

He rightly recognizes that distortions of Pope Benedict's teaching — and efforts even to downplay it — played a role in this radicalization of the American Catholic right. He notes that "Pope Francis is an anti-ideological Catholic who has made no secret of wanting to call off the 'culture wars.' This was perceived from the start by some bishops as incompatible with the challenges facing the Church in the U.S."

Faggioli draws out the clear political implications of these theological contretemps — and the theological consequences of the political changes that are afoot. "The fate of Biden's Catholicism in America is interwoven with the fate of Pope Francis's pontificate (that is, its long-term fate, even after the next conclave); both depend on what will become, in the United States, of Francis's proposal for an anti-ideological and anti-moralistic Catholicism."

Massimo Faggioli delivers the annual Anthony Jordan Lecture Series at Newman Theological College Feb. 28, 2015, in Edmonton, Alberta. (CNS/Glen Argan, Western Catholic Reporter)

This anti-Francis campaign is to ecclesiology what Donald Trump was to constitutional government: disruptive and vulgar. "The whole reception of Francis's magisterium, especially on social issues, is the story of a more or less subtle rejection on the part of the Catholic establishment, with more subversive tones and methods than the post-conciliar Catholic dissent of the 1960s and 1970s," he writes. His detailed account of the reaction of many bishops to the allegations proffered by disgraced former nuncio Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò — and his call for the pope to resign! — makes clear that for some time, the U.S. church is an outlier in the universal church, and that leading sectors of the American church are in a proto-schismatic state.

Not all of the tensions between Rome and the church in the United States are attributable to ideological cleavages. Part of it is simple myopia, which afflicts both left and right in the U.S.:

Francis's pontificate has sought to recognize and to listen to a global and polycentric Catholic Church. But this attempt to redefine the idea of the "center" of Catholicism has major consequences for the American Church, which tends to consider itself the center of the world – consciously or unconsciously, both in its conservative component (with its effort against theological liberalism, the pluralization of the religious world, and secularization) and in its progressive component (with its efforts in favor of a universalization of same-sex marriage, a feminist theology of the liberation of women, and a theologization of identity politics).

Rare is the Catholic academic willing to call out both ideological extremes, and Faggioli's willingness to do so only adds to the conviction that he is one of the few academic theologians who is not trapped in a boring echo chamber with secular academics.

Faggioli's subchapters on the "Ecclesial Metamorphosis in the U.S. and its International Consequences" is exceedingly well done, especially his treatment of the role and influence of conservative Catholic media. Similarly, in the very next subchapter, "The Biden Administration and the Vatican," Faggioli uses an important 2019 speech by Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Parolin, in which he spoke of a "positive neutrality," to discern the opportunities and the points of potential conflict between the new administration in Washington and the Vatican of Pope Francis. Geopolitical realities like the rise of China pose different challenges to the world's two most prominent, and mostly sympathetic, Catholics.

The final chapter is a tour de force, most especially the subchapter entitled "The 'Culture Wars' as an Ecclesial and Political Lifestyle." The decision to employ the word "lifestyle" is brilliant, novel and devastatingly accurate. His discussion of the difference between secularism and secularity should be required reading for our fretful bishops. If I could recommend one sentence in the entire book it would be this: "The challenge, both political and ecclesial, in the present emergency is to rebuild a sense of unity that marginalizes the extremes and treats the sectarian instinct as the epitome of non-Catholic spirit." It is terrifying to recognize the truth of Faggioli's insistence that the polarization too many Catholics, including many bishops, helped bring to birth has become an addiction.

One of my frustrations with this book, doubtlessly the result of its being hurried into print, is that it contains some observations that you can tell are pregnant with meaning and significance, but are not sufficiently explained to really grasp what that meaning or significance is. For example, when Faggioli speaks of John Kennedy's "choice to privatize his Catholicism and to secularize the presidency," I am not sure what he means by secularization in this context. Kennedy kept his Catholicism at arm's length, but he was knee-deep in the civic religion of the office and used that religion in his rhetorical Cold War battles.

When he writes that "the U.S. bishops' sympathies for Trump also depended on the fact that they, and U.S. Catholicism in general, did not have to learn democracy by dealing with fascism, as Catholics in Europe did before, during, and after World War II," I am sure he is on to something but I am not sure what, and the sentences that follow did little to flesh out precisely how democracy was learned differently in the U.S. and what any of that has to do with the bishops' embrace of Trump. I suspect it has less to do with how they learned democracy and more to do with the reckoning Europeans needed to make after their complicity with fascism, and the consequent understanding of conscience and its role in civic life, but I can't be sure because his prose here is unclear.

Advertisement

Other times, Faggioli is simply wrong. He begins with a historical survey, and they are always treacherous endeavors. Still, he is mistaken when he writes that the "acceptability of Catholics on the national political scene was strengthened by their faith's compatibility with mainstream Cold War liberalism's opposition to communism, but also by the treatment of the issue of racial segregation in the U.S. as irrelevant both theologically and politically." By the time of the Cold War, the Democratic Party had already witnessed a walkout at its 1948 national convention, so segregation was hardly "irrelevant" politically by that time.

One more difficulty, one of omission more than mistake, is Faggioli's failure to recognize the critical significance of Catholic migration to the suburbs in the postwar era as the sine qua non for all the other ecclesial and political changes he describes. He is right that Vatican II, and especially its teaching on religious liberty, helped Catholics enter the mainstream of political life, even though Kennedy was elected before Vatican II had even begun. And he is right that it was the reaction to the post-conciliar landscape that saw the birth of modern conservative Catholicism, even if certain preconciliar precursors, like the prudishness of the Legion of Decency, provided fertile soil for later iterations of pelvic theology. But the loss of a specifically Catholic identity, and the related and consequent diminishment of any claims Catholic social teaching might have on Catholic voters, began when Catholics became affluent and moved to the suburbs, where your identity had more to do with the car you drove than with the prayers you recited.

These difficulties are minor when compared to the accomplishment of the text as a whole. It is not just that Faggioli, like Alexis de Tocqueville before him, brings a foreign-born eye to his task, permitting him to see things we natives miss. Nor is it that Faggioli has immersed himself in profoundly complicated sociocultural terrain and mastered it. Nor is that Faggioli is, simply put, the outstanding U.S. ecclesiologist of our time, although he is.

What is most refreshing about this book is that it contains theology. He draws distinctions and makes arguments and presents evidence. He does not make assertions that are unproven. At a time when many theologians confuse pushing the envelope in ways that will get them published with being prophetic, Faggioli understands that one of the more central issues at stake in the fight with fascism and proto-fascism is precisely the demand that evidence and arguments be required, not rants appropriate for an activist but misplaced when coming from an academic.

Faggioli is not looking to sit at the cool table, he is looking to convince the reader. And his text is the most convincing explanation of the situation of the church in the United States I have read in a long time. Get this book. Read it with pen in hand. Dog ear its pages. Keep it close at hand. I shall.