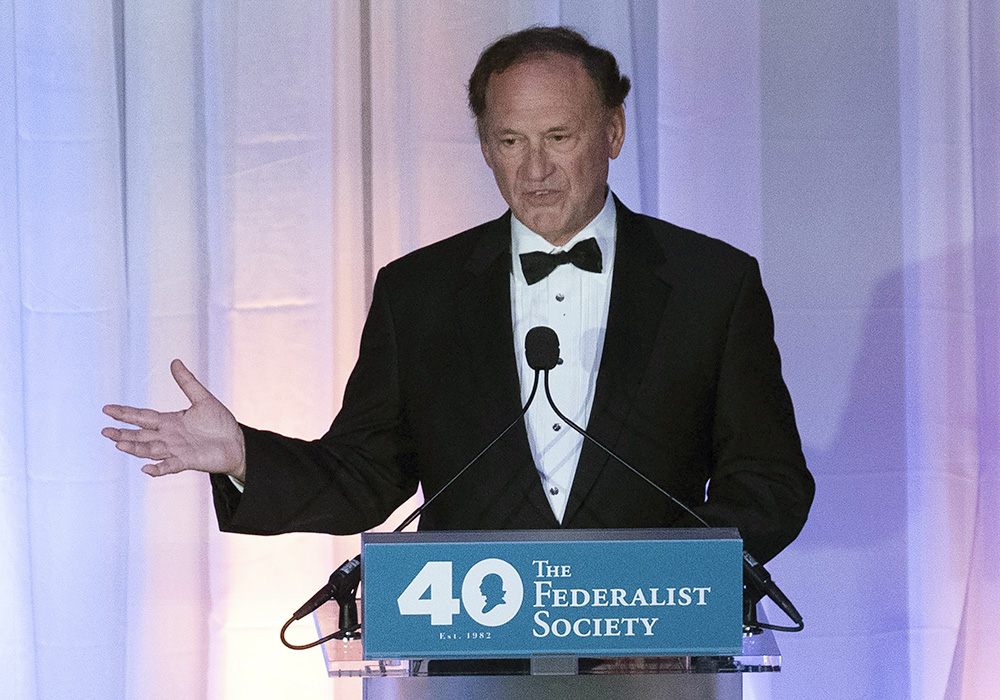

Supreme Court Associate Justice Samuel Alito speaks during the Federalist Society's 40th anniversary event at Union Station in Washington, D.C., Nov. 10, 2022. (AP/Jose Luis Magana)

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a landmark ruling in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization case, overturning nearly 50 years of settled law about abortion. The author of the decision, the four other justices who joined the majority and the chief justice, who concurred with the majority but did not agree to overturn completely the two court cases assuring the right to an abortion, were all raised Catholic.

The Dobbs decision, while hugely consequential in itself, reflects the culmination of a decadeslong campaign by conservatives to fundamentally alter the composition of the court and, by effect, the very nature of American life. This court and its Catholic supermajority are changing norms and jurisprudence on everything from gun control to the influence of money in political life, from the rights of workers to the voting rights necessary to maintain a democracy. Those who have worked to stack the court were even willing to cozy up with a morally reprobate person like former President Donald Trump to achieve their goals. Many of them cited their Catholic faith in doing so.

Such politicization of the judicial branch has many Americans challenging its legitimacy, with polls showing that confidence in the court is at an all-time low. Reaction to the Dobbs decision has already affected the outcome of this year's midterm elections, aiding pro-choice ballot measures and helping to elect some Democrats, and will likely influence our politics in the future. And it has deepened polarization in the Catholic Church, a major player not only in anti-abortion activism but in the politics of electing GOP presidents to pack the court with justices likely to overturn the 1973 decision Roe v. Wade.

At this vanguard of the ideological shift in the judicial branch is Associate Justice Samuel Alito, the author of the Dobbs decision, already known as one of the court's most conservative justices and now a pivotal figure in the movement. The National Catholic Reporter editors have named Alito our Newsmaker of the Year for 2022.

U.S. Supreme Court justices pose for their group portrait at the Supreme Court in Washington Oct. 7, 2022. Seated from left are Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, and Justices Samuel Alito and Elena Kagan. Standing from left are Justices Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Ketanji Brown Jackson. (CNS/Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)

Alito was nominated by George W. Bush in October 2005 and confirmed by a 58-42 vote in the Senate in January 2006, replacing the more moderate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor. Among his first majority opinions for the court were ones limiting employment claims for sex discrimination, one against environmentalists and one upholding faith-based programs.

He has joined conservative majorities in cases dealing with abortion, gun ownership, labor unions, voting rights and the death penalty. Alito wrote the decision in the 2014 Hobby Lobby case that said private corporations could be exempt from generally applicable laws, such as the Affordable Care Act's requirement that health insurance provide birth control, on the grounds of religious liberty.

Alito was the driving force behind and wrote the majority opinion in 2018 in Janus v. AFSCME, which dealt a blow to public-sector labor unions and the labor movement in general. In 2010, he wrote the court's decision striking down state bans on handguns in the home, noting that the right to keep and bear arms is "deeply rooted in the traditions of the country." (He would use the same language in Dobbs to argue that privacy rights are not "deeply rooted.")

In death penalty cases, he supports capital punishment, even arguing that attempts to limit executions by calling a method cruel and unusual punishment would mean that inmates would have to identify an alternative method. He joined the majority in 2013's Shelby County v. Holder case, which gutted portions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and led to a flood of voter suppression schemes in its wake.

Advertisement

In his dissent in the 2015 case Obergefell v. Hodges, which guaranteed the right to marry to same-sex couples, Alito expressed concerns about its effect on those with more conservative religious beliefs and values. "I assume that those who cling to old beliefs will be able to whisper their thoughts in the recesses of their homes," he wrote, "but if they repeat those views in public, they will risk being labeled as bigots and treated as such by governments, employers, and schools."

He also is aligned with the Federalist Society, the conservative and libertarian legal organization led for years by Leonard Leo, who is said to have played an "outsized role" in shaping today's Supreme Court. As a "contributor" to the society, Alito has spoken at several of the organization's events and clearly aligns with its judicial philosophy.

The Dobbs decision — which said that the right to an abortion was not included in the Constitution because it is not explicitly mentioned and because its substantive right to privacy is not "deeply rooted" in the country's history — relies on the legal philosophy known as "originalism," which seeks to use the founding document's original intent to interpret contemporary issues.

Roe was "egregiously wrong from the start," Alito wrote. "Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences. And far from bringing about a national settlement of the abortion issue, Roe and Casey have enflamed debate and deepened division. It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people's elected representatives."

The strategy and activism that led to Dobbs have had many negative ramifications — for our politics and our church — that need to be considered in the moral calculus.

By gutting Roe v. Wade and the 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the two rulings that guaranteed federal abortion rights, the Dobbs decision returned the power to regulate abortion to the states. Abortion bans began taking effect immediately, with most abortions now banned in at least 13 states (In addition, Georgia bans abortion at about six weeks of pregnancy, before many women know they are pregnant.)

The ruling — or more accurately, how people learned about it — also may affect the Supreme Court itself. In an extraordinary breach of the court's norms of confidentiality, a leaked draft of Alito's majority opinion appeared in Politico weeks before its publication, prompting the chief justice to order an investigation by the court's marshal. Last month, a New York Times investigation found that friends of the Alitos' told an anti-abortion activist about the Hobby Lobby decision weeks before it was published in 2014. Justice Alito, in a statement issued through the court's spokeswoman, denied disclosing the decision.

We recognize that many Catholics cheered the Dobbs decision, genuinely believing that it will protect human life. Whether one agrees with that or not, it cannot be denied that the strategy and activism that led to Dobbs have had many negative ramifications — for our politics and our church — that need to be considered in the moral calculus. Many of these come from Catholic leaders, and voters, who insist on prioritizing abortion above all other issues and neglect to acknowledge the role of conscience and compromise involved in living in a pluralistic democracy.

Alito has said publicly that he recognizes that his judicial decisions affect people. "It's important to keep in mind that these decisions are not abstract discussions — they have real impact on the world," he said at a September inaugural lecture for the Project on Constitutional Originalism and the Catholic Intellectual Tradition at the Catholic University of America's law school.

That is true and it is newsworthy, though — as we have seen in the decisions about gun rights, labor unions, the death penalty, abortion and the coopting of our democratic process for one aim — Alito's impact is certainly not worth cheering.