People at the Smyrna Community Center in Smyrna, Georgia, visit an early voting location Nov. 3, 2022, during midterms. During their 2022 fall general assembly, U.S. bishops voted to keep their document "Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship" and supplement it with inserts, social media components and an introductory note. (CNS/Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

For decades, timed with each U.S. presidential election cycle, the U.S. bishops regularly drafted a guide for faithful political engagement. That stopped with the papacy of Pope Francis. Why is unclear. As we celebrate the 10th anniversary of Francis' election, what is clear is the need for a new document, one that speaks to the sweeping changes that have occurred in America and globally, and one that reflects this papacy's sharpening of church teachings about the role of the church in the world.

The last guide, "Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship," was drafted in 2007 amidst lingering Catholic division following John Kerry's 2004 presidential candidacy and that election’s Communion wars. It reads like a time capsule of that era. While much should be admired about "Faithful Citizenship," America and the world have seen dramatic changes in the intervening years.

Pope Benedict XVI greets Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio at the Vatican in this Jan. 13, 2007, file photo. Bergoglio was elected March 13, 2013, the 266th Roman Catholic pontiff and the successor to retired Pope Benedict. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

In 2007, Benedict XVI was pope. The Gulf War was raging. The first iPhone appeared and social media was in its infancy. AI, data mining and gene editing were not yet things. Human-caused climate change was a theory still in doubt. Roe was still settled law; LGBTQ rights were not. It was written before the Great Recession, #OccupyWallStreet, #MeToo, the Arab Spring, Black Lives Matter, fake news, Russia's invasions of Ukraine, surging white Christian nationalism and before Jan. 6.

The year 2007 also marked a meeting of Latin American bishops in Brazil, at Aparecida, from which a pastoral theology emerged, championed by Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio. Six years later he would be pope and that theology refocused the church's role in public life.

Putting the Gospels ahead of canon law, Aparecida theology takes Christ at his word in Luke's Gospel where he reads from Isaiah, "The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring glad tidings to the poor." Francis speaks similarly of Matthew 25 and the Beatitudes, as the "twin pillars of Christianity." Within days of the papal election Francis remarked, "Oh, how I would like a poor Church, and for the poor," reflecting the heart of Aparecida theology and offering a touchstone for rewriting "Faithful Citizenship."

Since the early Church Fathers, Christianity has taught that politics must be for the common good of the whole community. Inspired by the Gospels, Aparecida offers the gauge of the common good to be the lived life of the poor. That insight bears repeating: The measure of the common good is the lived life and dignity of the poor. The measure of civilization is the life and dignity of the poorest among us.

A man holding a rosary with the U.S. flag as a backdrop is silhouetted in this photo illustration. (CNS illustration/Catholic Courier/Mike Crupi)

The poor of whom the Gospels speak are not only those without money. They are those on the peripheries of society — the ignored, powerless, oppressed, discriminated against, immigrants and refugees, racial minorities, the imprisoned, the elderly, the sick, those not yet born and even abused creation itself.

Christian citizenship calls us to measure engagement in public life for what it means for the life and dignity of these poor. Every law, policy, institutional procedure and social norm must reflexively and continuously be considered against the criterion that is the real lives of these "poor."

If this sounds like charity, it is. Reiterating his predecessors, Francis locates politics among the highest forms of charity. Yet, charity (caritas) cannot be downward-looking pity that reinforces marginalization. Politics as charity must open itself to those on the periphery and bring them into communion, brotherhood and sisterhood, and into a just equality with all.

Advertisement

As Francis explains in Amoris Laetitia, this is done by: welcoming, accompanying, discerning situations and integrating. It is also synodal inasmuch as the church's role in public life is not to judge, but to be open to the world (never closed), listen and dialogue. True politics is caritas, directed toward the common good, the measure of which is the life of the poor.

Would this mean that the work of governing and political engagement should never be concerned about other matters like the economy, transportation, agriculture or even the military? Not at all. It means that such policies can only be right when they improve or at a minimum do not further harm those whom Christ in Matthew 25 calls the "least" among us.

Previous political guides from the U.S. bishops were informed by canon law, judging policies and candidates against church ordinances. The Holy Father, however, has remarked that church teaching is best without "shall nots," that instead a genuine encounter with the word of God and with the person of Jesus Christ must be foundational — much as Aparecida theology emphasizes the Gospels. Similarly, a new "Faithful Citizenship," informed essentially by concern for the poor, would put evangelization and a positive vision for Christian political life center stage.

The Holy Father criticizes the idea of Catholic or Christian political parties and utterly rejects any imagining of Christian political life as a crusade of holy warriors against sinners. In his encyclical Fratelli Tutti and elsewhere, he speaks of "a better kind of politics" in contrast to the low-form politics too often seen in practice.

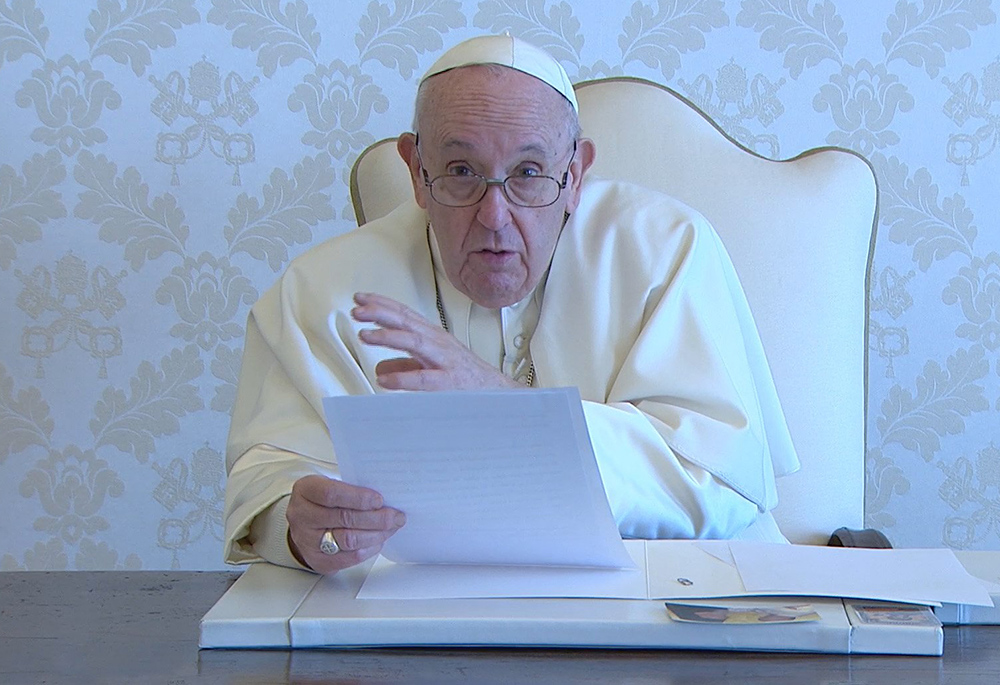

Pope Francis speaks in a video message to an online international conference on "A Politics Rooted in the People" in this still image taken from video released April 15, 2021, by the Holy See Press Office. (CNS/Holy See Press Office)

A better kind of politics is not ideological, not partisan, open to dialogue (not closed in self-righteousness), directed to the common good (not private interests), wielding caritas (not power), and ever intent on building bridges rather than walls of us-versus-them. Understood in this way, he reaffirms traditional church teaching on the true nobility of politics and public service.

It might be objected that rewriting "Faithful Citizenship" from the Gospels' emphasis on the poor lacks the specificity and juridical edge that came with terms such as "intrinsic evil," "material cooperation" and "non-negotiable." Yet, with the lived life of the poor as the measure of the common good, a wide-ranging, comprehensive theory of government and politics can be discerned and a general vision for promoting policies and laws is evident.

With the lived life of the poor as the measure of the common good, a wide-ranging, comprehensive theory of government and politics can be discerned and a general vision for promoting policies and laws is evident.

Concerned with lifting up the marginalized and bringing those on the peripheries into solidarity, and recognizing the equal dignity of all and empowering the powerless, the Aparecida approach would support democracy for all, diverse inclusivity, expansive human rights and popular sovereignty. Accordingly, the power of the state would also be limited and checked. These are the earmarks of liberal governance.

Similarly, a broad vision for policies is evident the Aparecida approach. It would encompass everything from assisted housing and health care to education and employment. Welcoming refugees and migrants, caring for creation, peacebuilding, anti-racism and developing an economic system that does not overly reward some while impoverishing others — these too are evident policies of a noble politics measured by what we do for the life and dignity of those on the peripheries.

"Faithful Citizenship" was written for a different time, amid different demands for faithful citizenship. It was written before Pope Francis offered the church his insight for refocusing the role of the church in public life. American Catholics need a new document, one that speaks to our new times and one that reflects the teachings of this papacy.

Editor's note: Schneck's views are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom.