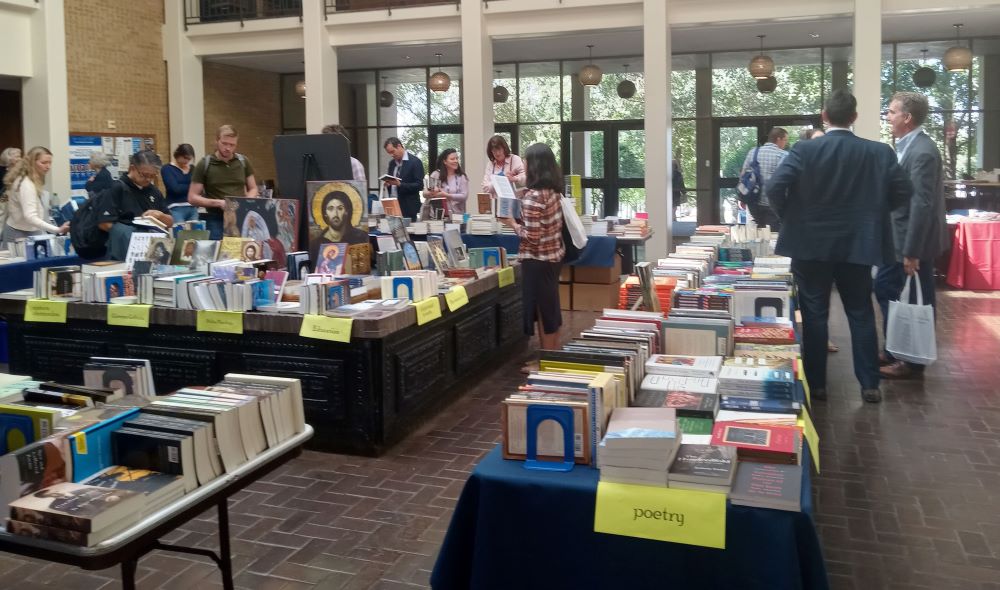

The Catholic Imagination Conference, held Sept. 30-Oct. 1 at the University of Dallas, included a book fair featuring small Catholic presses. (Photo by Jeannine Pitas)

"So are you ready?" one of my co-panelists asked me as we took our places at the front of the room, which was significantly more filled than I was expecting at 8:45 a.m. on a Friday. While literary translation, my main creative practice and academic discipline, is infinitely interesting to me, I often find it hard to communicate my passion for translating Spanish language poetry to others.

But the biennial Catholic Imagination Conference, founded by poet Dana Gioia and first held at the University of Southern California in 2015, brings together a community of Catholics who share a love for the arts, particularly the written word. After large gatherings at Fordham University in 2017 and Loyola University Chicago in 2019, this year saw a smaller gathering Sept. 30-Oct. 1, organized primarily by Jessica Hooten Wilson at the University of Dallas. I was honored to speak on translation alongside some inspiring co-panelists, all translators and writers in different areas.

"Emotions are embodied," stated my co-panelist Jason Baxter, a medievalist who is working on a new translation of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. His talk focused on the mixture of high and low diction in Dante's classic and the need for a new English translation that reflects this constant "code-switching."

Michial Farmer, a teacher at a classical high school who translates plays by Gabriel Marcel, told the story of how he simultaneously stumbled into the vocation of translation while converting to Catholicism. "The root word for 'translation' is very close to 'betrayal.' This is due to the reciprocity between the translator and the translated text," he said.

Then it was my turn. "Translation is about so much more than words on a page," I told the audience. "It's about relationships, about the communion of saints bound together through language."

The panel finished with poet and translator Frederick Turner, who argued that because language is intimate and private, all poetry is already translation. "It's about finding the human connection, something universal underlying our experience," he said.

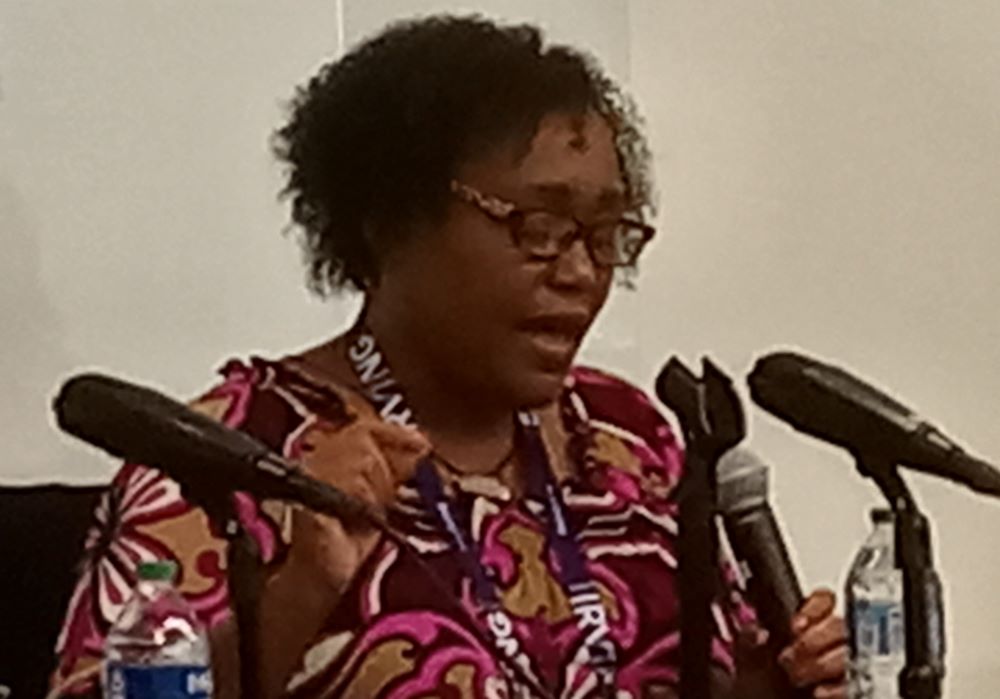

Speaker and nonfiction writer Gloria Purvis addresses the Catholic Imagination Conference, held Sept. 30-Oct. 1 at the University of Dallas. (Photo by Jeannine Pitas)

After that early session, the conference continued with two days of readings, workshops, more panels, a jazz concert with songs based on the poetry of Gioia, and a staged reading of the Will Arbery's play "Heroes of the Fourth Turning." Other highlights included readings by acclaimed Nigerian fiction writer Uwem Akpan, who read from his recently published New York, My Village, and Harper's Magazine editor Christopher Beha, who read from his novel The Index of Self-Destructive Acts.

"We've not figured out how to transmit our faith to the young," said Akpan, arguing that we need to look beyond divisive political issues. "What can we treasure from our Catholic heritage? The faith is rich. The Jesuits speak of finding God in everything. There is so much more we can do."

"Committing yourself to a life of the imagination is a defense of metaphysical thinking," said Beha, arguing that creative artists have a crucial role to play in the public sphere. "Contemporary culture is hostile to the imagination in general. Reality is seen as a set of facts transparently available. But the sacramental view is that reality is something we are participating in, and so is God. Reality is strange and surprising and can't always be assimilated into our existing context."

Reading from some recent pieces, nonfiction writer and consistent life activist Gloria Purvis spoke of the need to live what we say we believe.

"The pandemic held up a mirror and showed us not a loving God, but craven humanity," she said. "We were offered the cross and ran. Let us not just be preachers of the word, but doers of the word. The message we give to women considering abortion should be the message we give ourselves: choose life."

Advertisement

Gregory Wolfe, the publisher of Slant Books, said in a panel on editing that our task as Catholic writers is to bring a Gospel message into the secular world. "When we're talking about poetry, fiction and nonfiction, we need an incarnational view. Jesus' stories were about farmers, fathers and sons, the natural world. They didn't draw on Levitical religion," he said, adding that he sees literature as an antidote to tribalism. "A dualistic mentality is not a Catholic mentality. Ours is an incarnational, sacramental view. A deeper evangelical drive is to put stories into the larger world and trust that people with eyes will see, people with ears will hear."

In a panel on the future of the Catholic imagination, poet and conference organizing committee member Angela Alaimo O'Donnell described our arts as rich and varied, ranging from Dante and Giotto in the Middle Ages to Michelangelo in the Renaissance to Flannery O'Connor and Walker Percy in the 20th century United States.

"I'm nervous about 'the' Catholic imagination — I'd rather speak of 'a' Catholic imagination," she said. "I give my students new, updated syllabi every year so they read new, contemporary authors. We are planting seeds. Our church does not put much emphasis on the arts. This movement needs to come from us, not from the bishops."

Michael P. Murphy, Angela Alaimo O'Donnell and Dana Gioia at the Catholic Imagination Conference held Sept. 30-Oct. 1 at the University of Dallas. (Photo by Jeannine Pitas)

Bainard Cowan, a fellow of the Dallas Institute for Humanities and Culture and literature professor at the University of Dallas, was impressed that unlike typical academic conferences, this one offered a widely accessible message.

"This is not an ordinary conference, but one which requires all participants to explore how what they do stimulates imagination," Cowan said. "This is important for the humanities to survive. It's important for American culture. It was mind-opening and heart-opening."

Though the pandemic necessitated a smaller conference this year, I was delighted to connect and reconnect with writers and readers from across the U.S. and beyond. I left the event energized and already looking forward to the next conference, which is set to take place at University of Notre Dame in 2024. In a time of quick sound bites and dizzying news cycles, this conference offers all its participants a space to slow down, celebrate and imagine.