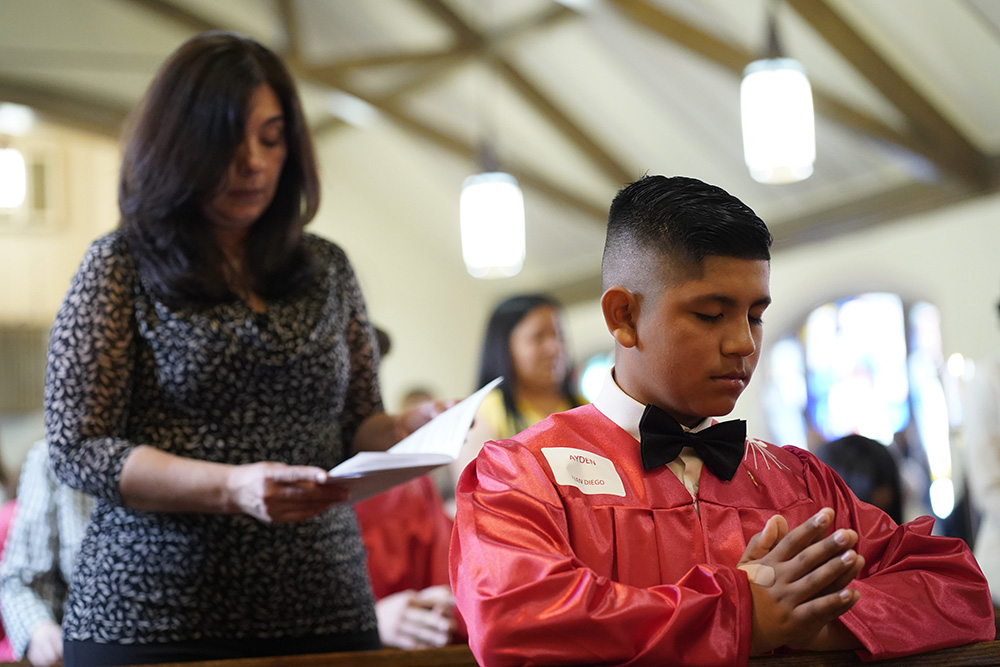

Confirmation candidate Ayden Morocho kneels in prayer as his sponsor, Grace Esposito, stands behind him during a confirmation Mass on May 5, 2022, at Holy Family Church in Queens, New York. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Last fall my 17-year-old niece asked me to be her confirmation sponsor. And when I traveled to Wisconsin for the ceremony this spring, I noticed that she seemed to be having some anxiety about it all. I wondered if she was having second thoughts about getting confirmed. But when we talked, it turned out her qualms had nothing to do with receiving the sacrament.

She was worried about the ceremony.

"Is it true the bishop is going to ask us questions?" she asked. I didn't know for sure, but it is pretty standard for the bishop to use the homily to have a chat with the kids, sometimes in the form of a Q&A, but usually playfully so. I tried to reassure her that this was not anything to worry about. She was not convinced. Her religious education teachers had given them things they needed to have memorized for the service, like the seven gifts of the Spirit. That didn't sound like the basis for a friendly conversation. "If I don't know the answer," she wondered, "do I fail?"

Advertisement

I don't know how the tradition of the bishop using his homily during a confirmation to do a Q&A began. If you think about it, it's actually pretty strange. In no other sacramental setting do we ask those receiving sacraments to prepare to be chatted up, let alone publicly quizzed. We don't do it with adults entering the church at the Easter Vigil. We don't do it at weddings for the couples getting married. We don't even do it at ordinations, a moment when some might argue the seriousness of the role being entered into, the impact that those being ordained will have on the people of God, merits a bit of public questioning.

Why would we refrain from asking questions in public of adults making major life commitments, and yet force teenagers to endure it? I suspect in most cases the answer has nothing to do with either the sacrament or any sense of examination. The fact is, congregations love it when a priest interacts with their children. It's entertaining and also sometimes surprisingly meaningful — kids really do say the darndest things. And while talking to kids in public can be personally unnerving for some clerics, it often humanizes them, too. For bishops, confirmation offers an opportunity to show a warm (and maybe funny) pastoral side.

The problem is, this practice has potentially serious negative implications for the teenagers who are actually there to receive the sacrament. In telling kids that they will be asked questions publicly, let alone that they should have certain data memorized, we are basically instructing them to understand their confirmation service as a kind of final exam. And not only that, but a public and oral one — something very few of us would relish under any circumstance.

Boston Auxiliary Bishop Robert Reed administers the sacrament of confirmation to a young woman at St. Bridget Church in Framingham, Massachusetts, March 11, 2023. (OSV News/The Pilot//Gregory L. Tracy)

Some might argue, is that such a bad thing? It is their confirmation, after all, their entrance into adulthood in the church. Why not think of it as the last part of their initiation? But again, this is not a practice we ask of anyone else, even as they take very significant life steps. More importantly, confirmation is not itself a test. It is a liturgy, a moment in which we ask the Holy Spirit to come down and fill the hearts of the confirmands. Creating a situation which causes them to enter in with anxiety or worse undermines their ability to experience that.

Construing confirmation as a kind of culminating exam also demeans all of the prior work that the confirmands have done. Those getting confirmed have had to do years of classes and class projects; volunteered, sometimes at multiple places; been on retreats; written a letter to their bishop; and maybe more. Each of those activities is significant, a moment in which they've been asked to stretch themselves and which we hope has helped them deepen their relationships with God and their sense of themselves as disciples.

We deem young people ready to be confirmed precisely as a result of these experiences. And it's those things that we should be highlighting at their confirmation — the ministry that they've done, the ways that they've come to know the Lord. Not what Catholic trivia they might be able to rattle off at a moment's notice.

As someone who has done my share of children's liturgies, I absolutely appreciate the impulse behind turning a homily into a playful Q&A. But when it comes to confirmation, we have to keep our eyes on who this is for, and what it's meant to offer. We want our children to be able to enter into their confirmations with hearts open to receive God's empowering love, not afraid they're going to be put through some embarrassing Catholic version of "Are You Smarter than a 5th Grader?"