Free copies of the Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano with the front page about Pope Francis' encyclical "Fratelli Tutti" are distributed by volunteers at the end of the Angelus in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Oct. 4. (CNS/IPA/Reuters/Sipa USA)

In his new encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis invites all people of goodwill to begin to imagine "a new vision of fraternity and social friendship." Inspired once more by his namesake, St. Francis of Assisi, the pope had begun writing about fraternity and dialogue when the COVID-19 pandemic "unexpectedly erupted, exposing our false securities."

The pandemic has exposed fissures previously overlooked and issued a stern reminder that finitude and fragility cannot be avoided. Everything and everyone is connected. As I often tell my students, natural disasters, sometimes only briefly, focus our attention to reveal the injustices and inequalities otherwise overlooked by those in power.

Diagnosing our current context, the pandemic demands our immediate attention, but it is the globalization of indifference that is our most insidious comorbidity.

On Aug. 5, Francis began a weekly general audience series on Catholic social teaching in the midst of COVID-19. Nine weeks that were focused around the most basic principles of Catholic social teaching began with an invitation to "reflect and work together, as followers of Jesus who heals, to construct a better world, full of hope for future generations."

For those unfamiliar with Catholic social teaching, these nine audiences provide a primer into how Francis understands human dignity, the universal destination of goods, solidarity, subsidiarity and such concepts. For those well-versed in Catholic social teaching, these messages provide some added theological depth to the encyclical's application of the concepts to larger social and economic crises.

Within Fratelli Tutti, there is an immense amount of content. It synthesizes much of Francis' social magisterium. The goal is to draw all people of goodwill into a long-overdue conversation about the practical moral obligations within the one human family.

I want to reflect just a bit on what the text says about the moral obligations of solidarity, which Francis first addresses using the paradigm of the parable of the good Samaritan and then applies to our world through his reflections on the universal destination of goods. I also want to address a lacuna in the encyclical: the perspective of women.

Advertisement

How do we understand our positive moral obligations within the one human family? I live in New York City, and the pandemic has made me appreciate Immanuel Kant anew. For Kant, moral actions and principles should be universalizable. When deciding whether or not to wear a mask or engage in communal activity, we should ask ourselves, would it be permissible if everyone acted as I act?

Kant's duty-based ethic acts as a dam against a flood of individuals all treating oneself as the exception to the rule. It posits negative duties (do no harm) as absolute and positive duties as imperfect and contextual.

The focus on universalizability, in an American context, has become highly individualistic.

For far too long, for example, conversations about racism focused on individual actions alone — ignoring a positive obligation to promote anti-racism. I have a perfect obligation to avoid actively violating your human rights, but do I have any firm obligation to promote your human flourishing and your integral human development?

Francis laments "insufficiently universal human rights," and a globalization of indifference in which no one feels responsible for their neighbor — a persistent theme of his pontificate. Underlying his critique is a deeper unexamined fissure within contemporary Western moral philosophy concerning our moral obligations.

Over the years, Catholic social teaching has endorsed global developments like the responsibility to protect, the Global Compact for Migration and calls for United Nations reform. But ultimately, the secular liberal vision for implementing human rights was not built upon a strong moral framework of positive obligations toward the distant other, and so progress lags. Since positive obligations are vague and imperfect, debates become about a failure to reasonably consider action rather than a moral obligation to act.

"The Good Samaritan" (circa 1618-22, detail), attributed to Domenico Fetti (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The parable of the good Samaritan provides an alternative. It lays out clear, positive moral obligations to our neighbor, including those who, in one way or another, are distant. As Francis notes in the encyclical's second chapter, "Certainly, he had his own plans for that day, his own needs, commitments, and desires. Yet he was able to put all that aside when confronted with someone in need. Without even knowing the injured man, he saw him as deserving of his time and attention" (Paragraph 63).

The beauty and challenge of this parable is how deeply concrete it is. Written as a meditation that invites both believers and all people of goodwill into deep personal reflection, this second chapter provides the core of the encyclical as a whole. It also articulates a moral theology in which we have positive obligations to those suffering or in need within the one human family.

It is a highly contextual and exacting moral vision. Perhaps the most remarkable element here is that Francis and Catholic social teaching have faith that, individually and collectively, we can all become like the good Samaritan. It is precisely this leap of faith required that sometimes leads others to critique Catholic social teaching for its naive optimism.

Our moral obligation to our neighbor, as explicated in Chapter 2, provides the lens through which the encyclical's passages on international economics, private property and the universal destination of goods should be examined. While they are fiery in tone and uncompromising in judgment, the economic passages in Fratelli Tutti mostly restate the longstanding Catholic moral tradition and apply it to today's context.

Reminding us that this goes back to the very beginning, Francis quotes fourth-century St. John Chrysostom: "Not to share our wealth with the poor is to rob them and take away their livelihood. The riches we possess are not our own, but theirs as well." The universal destination of goods — this belief that the goods of creation are destined for humankind as a whole — helps us imagine what it means to be one human family and who we are called to be.

Positive obligations toward my neighbor should govern questions of economic justice. And when one's neighbor is in need, meeting basic needs trumps any questions of their moral character. The universal destination of goods is primary. The right to individual private property is secondary, and always in service of the common good.

Fratelli Tutti helpfully argues with precise clarity that positive moral obligations of the universal destination of goods are not bound by borders and are operative on levels of the global economic apparatus.

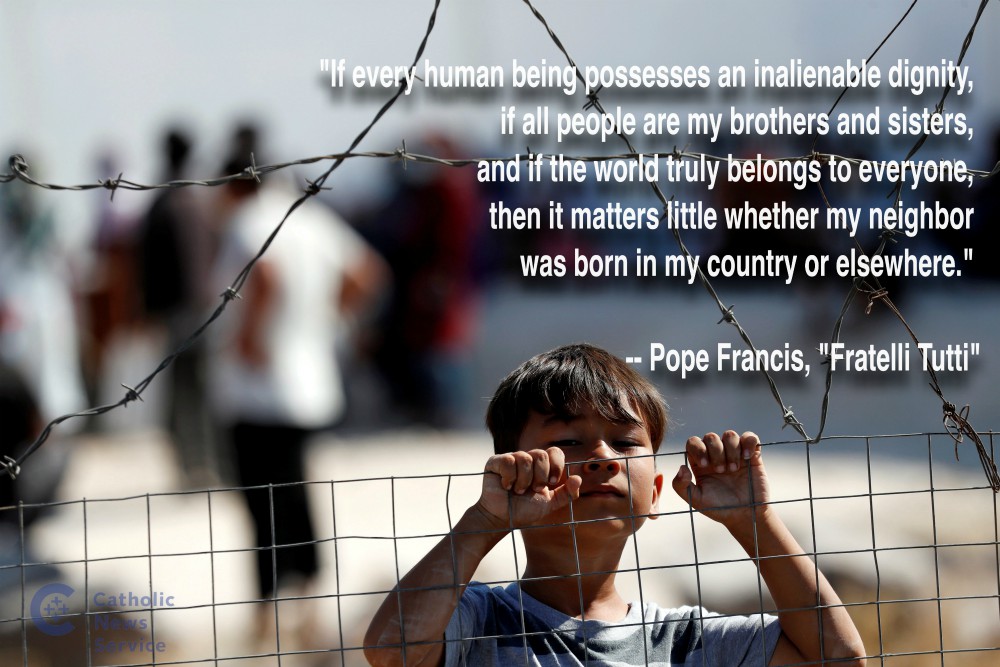

In particular, Francis identifies both positive and negative moral obligations of nations, stating, "If every human being possesses an inalienable dignity," then "it matters little whether my neighbor was born in my country or elsewhere." Every nation has responsibilities to the one human family; and this responsibility can be met either by offering "a generous welcome to those in urgent need, or work to improve living conditions in their native lands by refusing to exploit those countries or to drain them of natural resources, backing corrupt systems that hinder the dignified development of their peoples" (Paragraph 125).

(CNS illustration/Photo by Yara Nardi, Reuters)

Taking to heart Fratelli Tutti, and especially its economic and political moral obligations, would drastically change the calculation for what is asked of Americans — as individuals, communities and as one nation — with respect to those migrants journeying to seek asylum. We are not only asked to provide welcome, but also both to avoid participating in their oppression and positively support their development.

Our responsibilities are not bound by borders but by our common humanity. Repeatedly, the encyclical calls for listening at the margins, developing policies from the bottom up, and building a radically different social, civil and political global community.

Yet, amid this, women are largely absent. The lack of full human rights for women is mentioned three times (Paragraphs 23, 121 and 136) and women as victims of violence twice (Paragraphs 24 and 227). But despite a real emphasis on inclusive humanity within the text, no women are cited as inspiration, used for theological reflection or given as examples.

At the very end, despite the pope saying he's been inspired by "brothers and sisters" it is only three men Francis lists: Martin Luther King Jr., Desmond Tutu and Mahatma Gandhi. This is particularly striking because much of the local community-building work called for by this encyclical is practiced and embodied by women, especially within the contexts of migration and post-conflict reconciliation.

With this third encyclical, Francis has given us much wisdom. Yet, while recognizing "the organization of societies worldwide is still far from reflecting clearly that women possess the same dignity and identical rights as men. We say one thing with words, but our decisions and reality tell another story" (Paragraph 23), the lens still doesn't quite get applied to the church itself.

[Meghan Clark is an associate professor of theology and religious studies at St. John's University in New York. She is the author of the 2014 volume The Vision of Catholic Social Thought: The Virtue of Solidarity and the Praxis of Human Rights.]