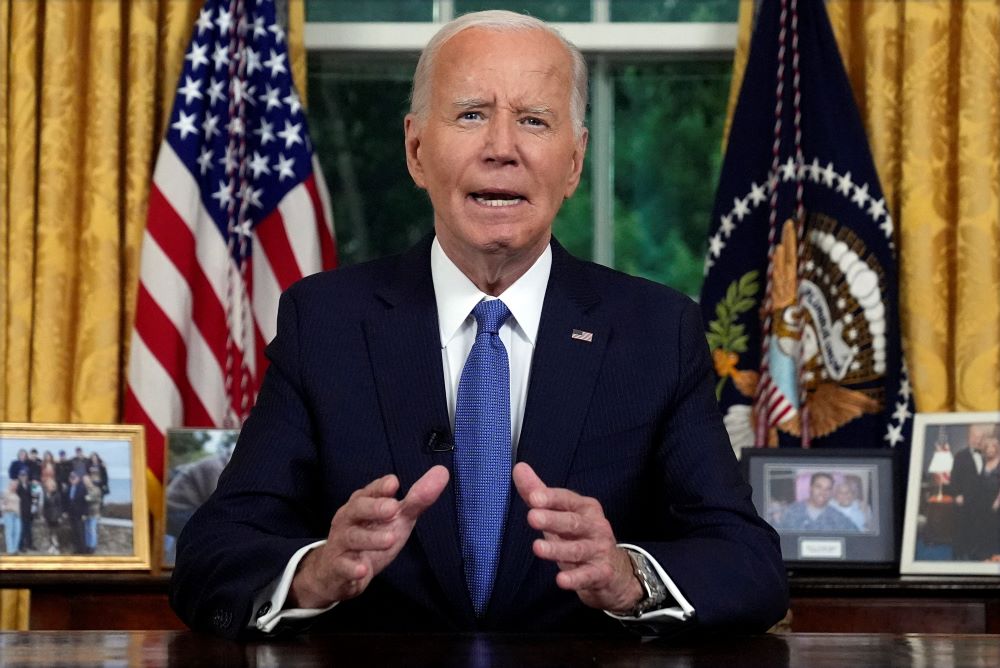

U.S. President Joe Biden addresses the nation from the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, July 24, about his decision to drop his Democratic presidential reelection bid. When the Biden administration ends, writes Steven P. Millies, a post-Catholic era of American life opens. (OSV News/Reuters/Evan Vucci)

Last spring when NCR offered me a chance to contribute regularly, I decided early on to write six essays that would have some thematic unity for this election year.

I've written about the ground shared between politics and our faith, the way that Catholics' support for religious liberty has become weaponized, the ways in which our public witness has come to resemble the worst fears of church critics, the role that outside money has played in transforming how the church meets the public square, and how a "sign of contradiction" narrative has come to overwhelm how Catholics think about the world we live in.

Together, those five essays all point toward the presidential election in November. They offer a sort of a summary of the state of play for Catholics in U.S. public life in 2024. And even though I imagined this sixth essay somewhat differently six months ago when Joe Biden was going to be on the ballot, a Catholic is the Republican vice presidential nominee today.

Indeed, the candidacy of JD Vance actually intensifies the concerns I have meant to raise at this point about the situation of Catholics in American politics — which really are concerns I have about the church more broadly, too.

When the Biden administration ends in 2025, no matter who will win the election and succeed Joe Biden, an era will have definitively ended for Catholics in the United States. These six essays describe how. Another era will begin, and it should raise concerns for us about what it means, especially in light of the ascent of JD Vance as Biden leaves the stage.

"The Catholic vote," prized so much by analysts for so long, I think has reached the end of its practical importance.

Joe Biden matured into adult life and public life in a different era. That era had a long preparation in two generations of Bible scholars and theologians who recognized that the modern world wasn't going to go away and after four centuries the church would need to begin reckoning with it.

Joe Biden was formed as a Roman Catholic by that different era, the one characterized by the Second Vatican Council which gave formal ecclesiastical approval to the fact that the church must engage with the modern world, meet the modern world on its own terms. That "Vatican II generation" included Biden and millions of other Catholics. It even gave rise to the National Catholic Reporter and my own institution, Catholic Theological Union.

The decades that followed proved the hopes of that "Vatican II generation" to be too optimistic. There was an instant rejection of the council among people so devoted to the old liturgy that they could not imagine embracing the changes. But those traditionalists were a fringe. Mainstreaming their objections took a lot of time, effort and money. The decades that followed saw time, effort and money applied patiently.

Mainstreaming those objections took the shape of the "sign of contradiction" narrative that began to tighten its grip on the church after 1987. What better way could there be to discredit the council's call to engage the world than to insist that the church must contradict the world? In turn, this meant embracing attitudes in the church that held the secular state, other believers and the modern world in open disdain — the same attitudes that incited the anti-Catholicism that characterized the 19th and 20th centuries.

Religious liberty was embraced, but not in the way the council envisioned. Less like a call to respect "different cultures and religions," the Catholic defense of religious conscience in recent years has become something more like a one-way street that recognizes protections only for Catholics.

The effect of all of this has been to prioritize the Catholic Church and its voice above civic institutions that speak for all cultures and religions, abandoning our commitment to politics as "a lofty vocation and one of the highest forms of charity." And, to do all this across the last several decades has demanded vast sums of money that the church and its bishops do not control, but which has effected far-reaching changes in the church.

At the end of all that, this is where we are. "Catholic" in the broader public perception of what the church represents no longer reflects sisters and priests marching with civil rights protesters or the good works of someone like Dorothy Day. Surely the crisis of sexual abuse in the church did (and still is doing) its own damage to that image. But even that scandal itself is in many ways a symptom of the real problem: a church closed in on itself, isolated from the world and prickly in its defense of its own prerogatives. This is the post-Vatican II church that was chosen and built — not by all of us, to be sure, but it now is the one we all have.

A bishop votes June 14 at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' Spring Plenary Assembly in Louisville, Ky. " 'The Catholic vote,' prized so much by analysts for so long, I think has reached the end of its practical importance," writes Steven P. Millies. (OSV News/Bob Roller)

As Joe Biden was an icon of that earlier age of Catholicism in the United States that hoped for a church working fruitfully in and with the modern world, JD Vance is an icon of this new age where we find ourselves. A Catholic Church that had struggled for decades to win acceptance in the United States and become a national constituency in our presidential politics now is, for many, a cultural outlier, an interest group that makes odd statements not intended to win wide audiences and a niche faction of just one party. "The Catholic vote," prized so much by analysts for so long, I think has reached the end of its practical importance.

Where do we go from here? There can be no overnight recovery from this ruinous condition. It has taken 40 years to build this post-Vatican II church that is set against the world. Catholics of my relatively advanced age and younger have almost not known anything else. There is a lot to unwind.

It is important to remain hopeful, but we must also begin by letting go. To really engage the world, we must accept the world as it is. This will demand humility most from those who have worked so hard to realize Vatican II's promise. Yet, those who have insisted on the closeness of the church and the modern world should be the first to recognize that the world challenges us, it rejects the Gospel. And still, as St. Paul departed the skeptical philosophers of Athens to continue his work anew in Corinth, we keep trying.

Perhaps more substantively, we need to embrace the call to synodality. I am not one of those skeptics who has lost hope for the synod. I agree with Massimo Faggioli,who said "this is a Church that doesn't have enough priests and religious to be run and governed like it used to be," and synodality is "not something that can be ignored or denied for too long." This really is the answer, I think. It is a call to the whole church to reflect and act together, and the inclusion of so many voices will not be able to deny the world for very long.

Advertisement

A great challenge lies ahead in this post-Catholic era of American life that will open after the Biden administration ends. And yet, we are not entitled to abandon hope. No one has given us permission to quit. The work will be difficult, and change will come slowly. Like all things, in God's own time change will come.

Author's note: I'll be taking a sabbatical from both the Catholic Theological Union and NCR to pursue a book project. I may dive back in on occasion, as the spirit and the news allow. But I will put most of my focus on the project ahead of me.