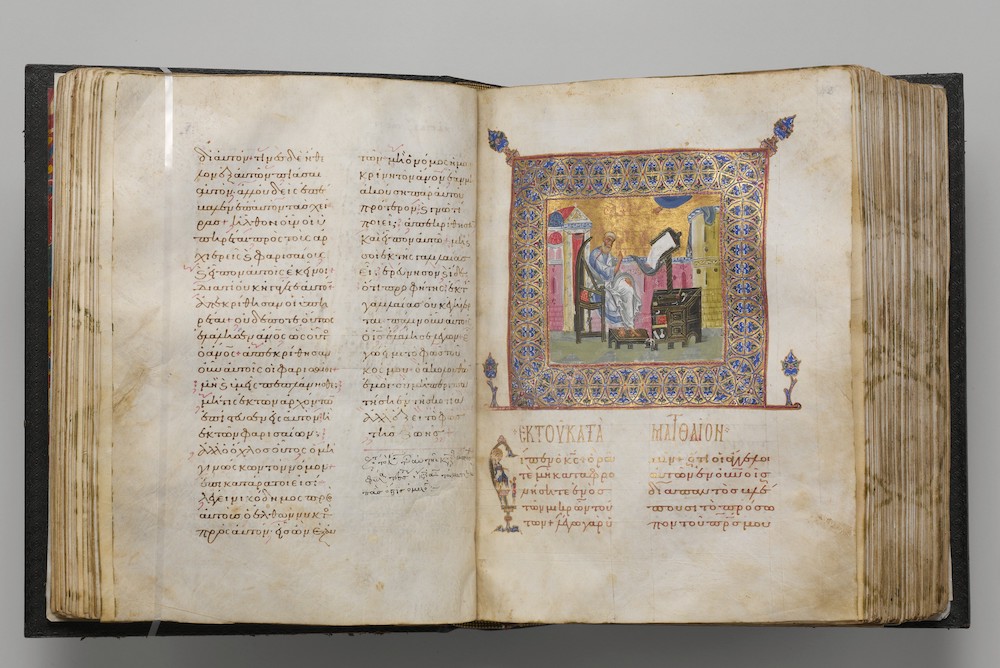

Jaharis Byzantine Lectionary, circa 1100 and made in Constantinople, open to folio 43 showing the evangelist Matthew (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

On March 10, I attended an online webinar, "Reading the Bible in the Lectionary: Gift and Challenge," offered by the School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College. The presenter, Ursuline Sr. Eileen Schuller, is professor emerita in the department of religious studies at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Her impressive resumé includes translation and publication of several Dead Sea Scrolls. She also worked closely with Canadian bishops on the preparation of the Canadian Lectionary for Mass, which is widely known for its use of more gender inclusive language.

Although Schuller's thoughtful presentation touched only tangentially on inclusive language, for me, it resurrected painful memories of the decadeslong struggle U.S. bishops engaged in with then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Their struggle ultimately failed to incorporate the inclusive principles originally sought by U.S. bishops in 1990. But more on that later.

Schuller prepared her presentation with the 50th anniversary of today's Vatican II lectionary in mind. She referenced Article 51 from the Constitution on the Liturgy, which in 1964 served as a mandate to the 20 some scholars working to revise a nearly 400-year-old lectionary. That article says: "The treasures of the bible are to be opened up more lavishly, so that richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God's word. In this way a more representative portion of the holy scriptures will be read to the people in the course of a prescribed number of years."

After five years of intensive work, the new lectionary was promulgated on the first Sunday of Advent in 1971.

A 50th anniversary, Schuller said, provides an occasion "for giving thanks and for looking to the future, but also for critique and evaluation." She then analyzed "how the [Sunday] lectionary, has and has not fulfilled the mandate that it was given."

On the plus side, 50 years of hearing more Scripture passages read at Sunday Mass have given Catholics a greater sense of familiarity with the Bible. This is an occasion for gratitude. On the problematic side, Schuller quoted from the Pontifical Biblical Commission's 1993 publication, The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church. After commenting on article 35 in the Constitution for the Liturgy asking that readings to be "more abundant, more varied and more suitable," the Biblical Commission document concluded: "In its present state, the lectionary only partially fulfills its goal."

While many evaluations and critiques of the lectionary have been made since 1993, Schuller focused on two issues: "omissions and what is and what is not included in the Sunday lectionary" and "how the Old Testament is presented."

Foremost among the omissions are passages about women, especially women in leadership roles. "The rich Biblical resources about the role of women in the Old Testament, and especially in the early Christian communities, are still simply unknown," Schuller said.

Her students frequently ask her, "Why didn’t I hear about them in church? Why haven't I heard these names Shiphrah and Puah (Exodus 1:17-22)?" Or: "Why have I never heard of Jesus healing the daughter of Abraham, the only Lukan miracle that is not included on a Sunday (Luke 13:10-16)? And women in the early church, Tabitha, Lydia and Priscilla?"

The second problematic area needing attention and revision involves the readings from the Old Testament. Schuller notes that Old Testament texts are too often "applied according to a patristic typological principle … by a simplistic prophecy-fulfillment relationship that easily slides into a supersessionism [the belief that Christianity supersedes or replaces Judaism] or, at worse, by a paradigm: 'Nice, good Jesus; mean, bad Jews.' "

Schuller offered helpful suggestions, such as supplementing the lectionary with good preaching, parish Bible study, and using omitted passages for parish meetings and prayer sessions.

In 2007, the Vatican approved the Canadian Lectionary's use of translations from the New Revised Standard Version, or NRSV, which according to biblical scholar Jesuit Fr. Felix Just are more inclusive and "positively disposed toward women, both by omitting some negative statements and by adding some positive comments."

Somehow the Canadian bishops were more successful in gaining Rome’s approval for inclusive liturgical texts than were U.S. bishops. On Easter Sunday, for example, Canadian Catholics hear Jesus' commissioning to Mary of Magdala to "go and tell my brothers" that he has risen (John 20:11-19). Schuller said this inclusion has been "very influential" in changing perceptions about women's biblical leadership in Canada, as has the inclusion of the Song of Miriam at the Easter Vigil (Exodus 15:1-21). Neither text is proclaimed in U.S. Easter celebrations.

As I listened to this webinar, I couldn't help but think of Bishop Donald Trautman of Erie, Pennsylvania, who went to a well-deserved eternal reward Feb. 26. For 30 years Trautman was an outspoken advocate for the use of inclusive language in both the U.S. Lectionary and in the Roman Missal. In 1997 he gave what was described as a "defense" of inclusivity after the Vatican insisted on a less inclusive version of the U.S. lectionary than the one initially proposed by U.S. bishops 10 years earlier

"It will be a sad day for Catholic biblical scholarship and even a sadder day for the pastoral life of the church in the United States if the new lectionary does not incorporate the principles of gender-inclusive language," Trautman said. “If biblical scholars from the fundamentalist tradition, who clearly revere the literal interpretation of the Bible, employ gender inclusive language and Roman Catholics are denied that opportunity, there is not just a liturgical problem, there is an ecclesiological problem of great magnitude."

Advertisement

In 2018, after the Pennsylvania Attorney General David Shapiro accused Trautman of covering up clergy sex abuse. Trautman staunchly defended himself: “Why would I cover up Poulson's sinful behavior when I had removed 22 priests from ministry and sought their dismissal from the clerical state?" Shapiro’s report was later sharply criticized as "grossly misleading, irresponsible, inaccurate, and unjust" in an exhaustive investigative piece by Peter Steinfels, a widely respected Catholic commentator and former religion reporter for The New York Times. Of Trautman's tenure in Erie, Steinfels wrote: "Trautman in particular acted with dispatch to remove these priests from ministry. He reached out personally to victims and did not discourage them from going to the police or prosecutors."

I do not wish to dwell on the labyrinthine issues underlying the horror of clergy sex abuse. Trautman's courageous advocacy on behalf of making biblical and liturgical resources accessible to the female half of the Catholic population should not be lost in the mire of mudslinging over clergy sex abuse.

In 2017 Pope Francis changed canon law and essentially returned control of local liturgical translations to where they belong — the world's bishops' conferences. While it is unlikely that the U.S. Lectionary and Roman Missal will be revised any time soon, Schuller finds a bit of hope in Proposition 16 of the 2008 Synod on the Word, which recommended an examination of the Roman Lectionary "to see if the current selection and ordering of the readings is truly adequate to the mission of the church in this historical moment." While Pope Benedict did not directly adopt Proposition 16, Schuller pointed to Section 57 in his post-synod response Verbum Domini, where he acknowledged "problems and difficulties" that "should be brought to the attention of the Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments."

Perhaps advocates could approach their bishops, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the 2023 Synod on Synodality to request a re-examination of liturgical texts in light of so many contemporary concerns about omitted and problematic readings. A reconsideration of psalter and lectionary texts originally approved by U.S. bishops in 1991 also seems to be in order.