(Dreamstime/Thai Noipho)

While most years the season of Lent feels as though it crept up on me, this year's unusually early arrival of Ash Wednesday and the formal launch of this liturgical time of penance and prayer has truly felt like a shock. This year, Lent began barely seven weeks after Christmas, which makes it one of the earliest starts to the season, which is determined annually according to when Easter falls.

Even on a good year, when I feel as though there's a little more breathing room between Advent/Christmas and Lent/Easter, when we have a few extra weeks of ordinary time before diving back into a special liturgical season, I often find myself struggling to decide what practices I am going to embrace to mark the time.

Inspired by Pope Francis' frequent exhortation to the faithful to "return to the basics" of our faith, especially when it comes to reading Scripture and embracing the Gospel, I thought it might be nice to begin Lent this year with a return to the fundamentals. Like well-known stories from the Bible, the liturgical seasons of the church year can become tiring, taken for granted and practices with zombie-like routine.

'Our journey toward God over the forty days of Lent includes a journey toward the suffering, because that is one place where God can be found.'

—Esau McCaulley

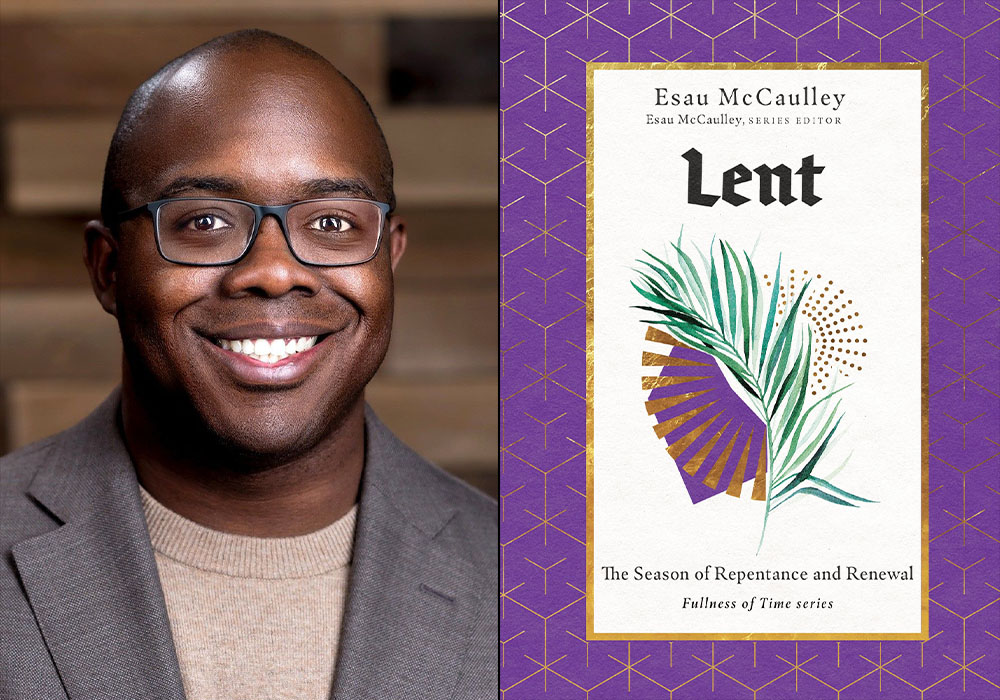

So, I decided to take an ecumenical approach and read Esau McCaulley's short 2022 book Lent: The Season of Repentance and Renewal.

One of the things I have come to appreciate about McCaulley, an Anglican priest and associate professor of New Testament at Wheaton College, is that he is one of those rare scholars who does not write only for other academics. In addition to his scholarly writing, he identifies as a public theologian, which includes serving as a contributing writer at The New York Times and authoring popular articles and books for broad audiences.

While there were of course little things here and there that I might quibble about from a theological or distinctly Catholic perspective, overall I really enjoyed this little book. It was exactly what I was looking for: a "back to basics" reflection on the season of Lent. McCaulley's well-written and accessible theological reflections offered insights that gave me a springboard for deeper reflection.

The structure of the book is quite simple. After a brief introduction to the season of Lent, McCaulley organized his reflections into four chapters followed by a short conclusion.

The first chapter (on Ash Wednesday) and the fourth (on Holy Week) focus on particularly important celebrations in Lent. The two middle chapters explore what McCaulley calls "The Rituals of Lent" and the prayers and lectionary readings of the season.

Anglican theologian Esau McCaulley and the cover of his book book Lent: The Season of Repentance and Renewal (Courtesy of IVP Press)

Early in the book, McCaulley summarizes the meaning of Lent, offering readers an invitation to reflect on where they are on their respective faith journeys and see how Lent is a meaningful time wherever one finds oneself.

Lent is a season of repentance and preparation. In many churches, it is a time when those who will be baptized prepare for their new life with God. It is a time when those who have been estranged from the church can be reconciled to the body of believers. It is also a time for all of us to think about the ways we have drifted from the faith. The common theme uniting these three functions of Lent is that they all involve a turning toward God with intention and reflection on the past.

I really like how inclusive this vision of the season of Lent comes across to the reader. Each of us can find ourselves in one of McCaulley's proposed three purposes and each of us can benefit personally and communally from more fully embracing "a season of repentance and preparation."

Reflecting on the traditional Gospel reading for Ash Wednesday (Matthew 6:1-6), McCaulley offers an interpretation that many Christians may find inspiring at the beginning of their Lenten journeys.

He writes: "Jesus highlights the dangers of fasting and other ceremonies that surround repentance. Before we begin this season, we must remember who it is for. The potential for self-deception is high. Any season of fasting or charity can turn into religion as performance instead of a service offered to God."

Advertisement

In recent years, various pastoral ministers and commentators have encouraged deeper reflection on why we do what we do during Lent. McCaulley likewise acknowledges that traditional practices like prayer, fasting and almsgiving can easily miss the mark if we treat them as ends in themselves or mistake the goal or purpose of the practices.

A classic example is when some Christians see fasting or abstaining from certain foods or drinks as a form of dieting instead of as a form of solidarity with those who may be suffering involuntarily, or as a reminder of our dependence on God.

McCaulley is good about tying the individual practices of spiritual renewal and penance not only to the broader Christian community, but to all people, especially those who are in any way marginalized or suffering.

Our journey toward God over the forty days of Lent includes a journey toward the suffering, because that is one place where God can be found (Matthew 25:34-46). Lent is not merely about extended reflections on our own mortality. It's a chance to open our lives and hearts to the pains of the world in imitation of our Lord, who looked with compassion on those with spiritual and material needs.

This reminded me of the beautiful insights of Pope Francis on the beatitudes of Jesus in his 2018 apostolic exhortation on Christian holiness titled Gaudete et Exsultate. In his reflection on "Blessed are those who mourn," the pope writes:

The world tells us exactly the opposite: entertainment, pleasure, diversion and escape make for the good life. The worldly person ignores problems of sickness or sorrow in the family or all around him; he averts his gaze. The world has no desire to mourn; it would rather disregard painful situations, cover them up or hide them. Much energy is expended on fleeing from situations of suffering in the belief that reality can be concealed. But the cross can never be absent.

Francis is making a point that is echoed in McCaulley's reflections: Namely, the Christian journey is about becoming more Christ-like, which places certain demands on us when it comes to seeing and responding to our siblings who are suffering and in need.

As the pope says, "A person who sees things as they truly are and sympathizes with pain and sorrow is capable of touching life's depths and finding authentic happiness. ... They discover the meaning of life by coming to the aid of those who suffer, understanding their anguish and bringing relief."

Because we are still at the beginning of Lent, there remains plenty of time to recalibrate our spiritual vision, thinking and heart to get back to the basics of this holy season.

Perhaps reading McCaulley's reflections will help renew your Lenten outlook, or maybe reading the words of Francis or some other resource will do the trick.

Whatever works best for you, it is good to keep in mind what McCaulley shares in his conclusion: "Our prayers, good deeds, fasts, and Scripture readings earn us nothing. Instead, they are Spirit-empowered means of entering into communion with Christ. They are about sharing the thing itself — the divine life."