A portrait of German philosopher Hannah Arendt in the courtyard of her birthplace in Linden-Mitte, Germany. (Wikimedia Commons/Hannes Grobe)

Anxious comparisons have become commonplace between Germany's slide into dictatorship in the 1930s and the rise of an authoritarian, populist nationalism in the United States today.

How should the Catholic Church in the U.S. respond to this troubling moment?

The work of the 20th-century political theorist Hannah Arendt can help. In particular, her writing makes clear the dangerous shortcomings of the culture war approach favored by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in their quadrennial document on elections, "Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship."

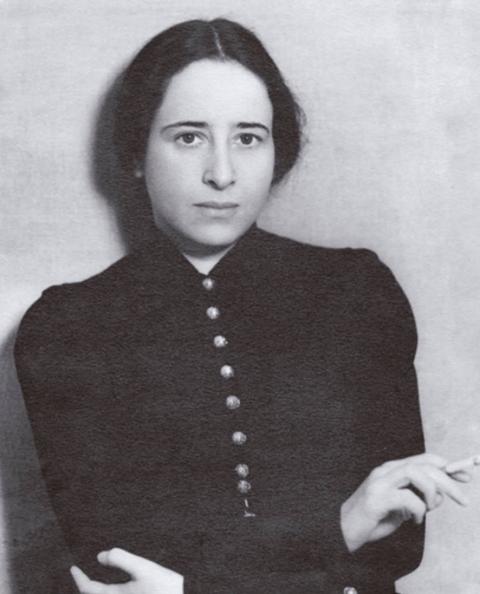

Arendt was a German-born Jewish philosopher and journalist who lived through the rise of Nazism and later wrote major works on all that went wrong in Germany. She was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933; then fled Germany and lived in Paris; and finally emigrated to the U.S. in 1941. She is best known for her monumental 1951 work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, on the Nazi and Soviet regimes. She also gained widespread recognition for her 1963 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.

German philosopher Hannah Arendt is pictured in a 1933 photo. (Wikimedia Commons/Yale University Press)

Echoes of Germany in the 1930s

Trumpian politics has deployed key aspects of fascist movements like Nazism: The use of mass propaganda and strategic lying; reliance on the rhetoric and practice of violence; dehumanizing speech about migrants and minorities; and a head-spinning willingness to give credence to the words of an authoritarian leader at the expense of basic fact.

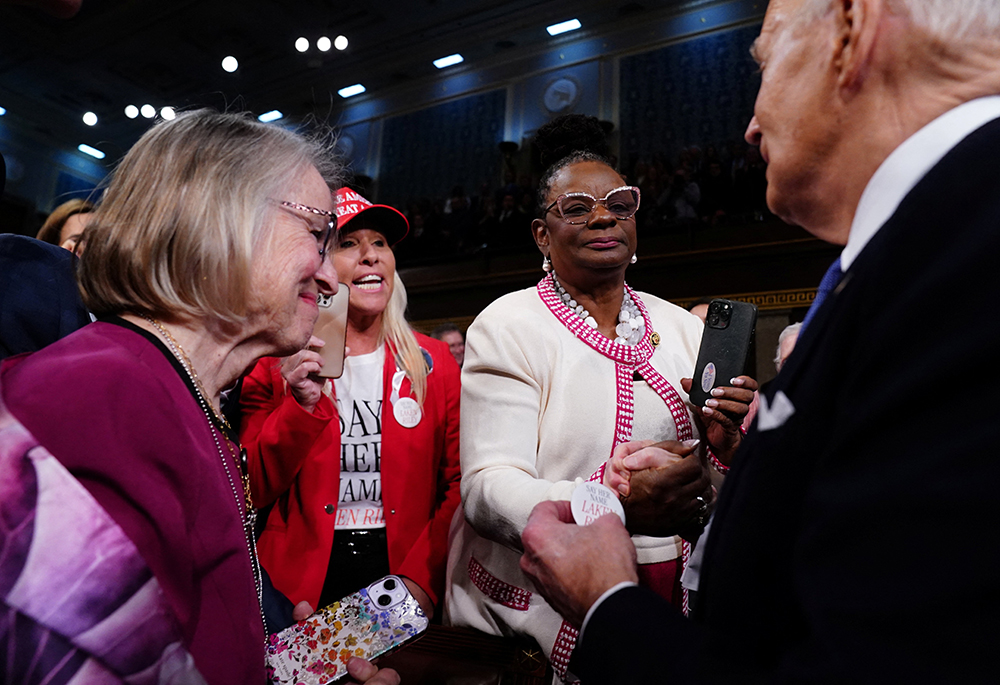

Of course, the authoritarian right in the U.S. itself believes they are fending off Nazi-like coercion at every turn. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia agreed with likening U.S. government public health leader Anthony Fauci's prudent efforts to fight the COVID-19 pandemic to Nazi medical experimentation. And GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump has compared the federal Department of Justice's scrupulously careful prosecutions of Trump to Gestapo-like tactics. Like others of many different political views, the American authoritarian right has also heard echoes of Nazism when identity politics descends into cancel culture (Arendt would have been an ardent opponent of cancel culture).

But, in usage by Greene and others, the label "Nazi" is chiefly a brand synonymous with "left" or "liberals" or "Democrat Party" — all generalized fictions that falsely lump huge numbers of persons of diverse convictions into one collective object of outrage (an outrage fueled by the algorithms and bots of social media). Here the terms "Nazi" and "liberal" and so forth play an important role in fostering the "friend-enemy" distinction made famous by Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt and favored today by many on the right.

In this "friend-enemy" view, we need to see that liberalism as a philosophy of governance is a pure power game, despite its constitutional niceties and pretense to seek peace amid pluralism. In this view, we also need to oppose by law and force and masculine toughness the "enemy" hiding behind such misguided tolerance.

U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, center, attempts to speak to President Joe Biden as he arrives to the House Chamber of the U.S. Capitol for his third State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress, March 7 in Washington. (OSV News/Reuters/Shawn Thew)

In any case, the point here isn't to brand people as Nazis but to reflect on the challenges to preaching the Gospel in word and deed in the face of today's currents of authoritarianism, populism and nationalism. One such challenge is that "Faithful Citizenship," the principal document by which the American Catholic bishops speak to the political order, doesn't address these troubling developments. The document takes democracy for granted; does not refer to the violent, unprecedented attempt to block the peaceful transfer of power on Jan. 6, 2021; and makes no mention of the vast, organized campaign of lies that claimed Joe Biden lost the 2020 presidential election.

But it's not just that "Faithful Citizenship" fails to acknowledge these matters. It is also that the document is shaped by a defensive moral theology indifferent to if not supportive of these troubling developments. This theology prioritizes the problem of intrinsically evil actions but not the plight of concrete persons; sees "preeminent" issues of reproductive and end-of-life ethics relative to all other topics as having a "special claim on our consciences and actions"; and looks longingly to state power to enforce laws consistent with a selective Catholic vision of moral truth that many bishops can no longer persuade people to heed.

In the view of such a defensive theology, authoritarian power enforcing conformity with Catholic truth can be a big help. By contrast, pluralist democracy and its alleged culture of permissiveness is part of the problem.

Advertisement

Politics, absolute truth and basic fact

Arendt can help us see the limits of this approach in light of four categories: truth, thinking, conscience and the "right to have rights."

At this political moment, we are faced with a paradox in the way that "Faithful Citizenship" values truth in politics. The document prioritizes an absolute understanding of moral truth manifest in the universal moral law as the key standard by which Catholics should make political decisions. At the same time, the document says nothing about the systemic lie that Biden did not win the election in 2020. How can a document that prizes such an absolute understanding of truth fail to mention such an unprecedented and consequential political lie? Arendt's extensive reflection on modern political lying can help us understand the significance of this paradox.

Arendt was attuned to the interaction between politics and different kinds of truth (e.g., religious and philosophical truth, scientific truth, absolute truth and factual truth). She noted, for example, that every claim of absolute truth (not unlike the claims behind the language of preeminence in "Faithful Citizenship") contests the purpose of politics: If we already know the absolute truth and its reflection in the law, then there is little purpose to the give-and-take of politics.

But she was especially concerned with the way that modern ideologies of political power sought at every turn to suppress the stubborn truth of unwelcome fact. This happened in the great 20th-century totalitarian dictatorships committed to ideologies of historical necessity or racial science — and it happened when open, democratic societies turned on themselves in service to ideologies of nationalism or populism. For Arendt, the issue was not so much the suppression of one interpretation or another of a set of facts (as problematic as such suppression could be). The issue was the way that political rulers sought to deny by systematic lying the existence of sheer fact, or what Arendt called "brutally elementary data."

German philosopher Hannah Arendt is pictured in 1958 at the Kulturkritikerkongress (Cultural Critics Congress). (Wikimedia Commons/Barbara Niggl Radloff, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Thus the vote count in the 2020 U.S. presidential election is reasonably subject to many interpretations: What were strengths or weaknesses for different candidates? How did certain districts vote? And so forth. But, in Arendt's terms, the vote count itself and Biden's victory is a piece of "brutally elementary data." In turn, the "Big Lie" of Trumpism in association with compliant political leaders; the most popular cable TV news channel; and millions of QAnon followers and social media junkies has tried every which way not simply to deny such "elementary data" but to remove it from history itself.

It is important to be clear: In a view consistent with Arendt's thought, the Big Lie of Trumpism is not a cost-free quirk of an idiosyncratic politician with his cheating heart in the right place. Instead, it's a manifestation of an amoral ideology of power with catastrophic effects. The systematic denial of "elementary data," she thought, was in fact an effort to destroy the reality that the data represent.

Moreover, she argued, systemic political lies about the truth of undeniable facts don't so much aim at persuading people to believe the lies as they try to foster widespread suspicion about every affirmation of truth. Such lies put at stake an elementary, common and factual reality without which there cannot be a political community, much less a common good. It is a great failing of "Faithful Citizenship" that it mentions none of this. Preoccupied with the abstractions of absolute truth, it sidesteps the political lies hiding in plain sight.

Politics and the problem of thinking

From the start of his papacy, Pope Francis insisted that "realities are greater than ideas." He has also often called out the ways that ingrained habits of thought make it harder to understand reality — for instance, the realities of human persons and the natural world — and its moral demands. Among those means of masking reality are "angelic forms of purity, dictatorships of relativism, empty rhetoric, objectives more ideal than real, brands of ahistorical fundamentalism, ethical systems bereft of kindness, intellectual discourse bereft of wisdom."

Throughout her work, Arendt also grappled with what it meant to think and to make moral judgments about the real world. To be sure, these are abstract philosophical categories. But her interest in such things was driven by an agonizing, concrete concern: How was it that Adolf Eichmann and so many others became participants in a regime of such ideological excess and murderous brutality? We tend to emphasize that the root of moral evil is in the will. Arendt wouldn't disagree — to an extent. But she — like Pope Francis and unlike "Faithful Citizenship" — also put great weight on the ways that deceptive habits of thought that allow us to avoid the reality of other persons set us up for moral failure.

Adolf Eichmann, pictured at trial in Jerusalem, in 1961 (Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain/Israel Government Press Office)

Eichmann was a case in point. Arendt argued that his great flaw was his refusal to think or, as she put it, "his almost total inability ever to look at anything from the other fellow's point of view." For her, to think in such a way neither meant that one had to understand the world precisely as another does nor that wholesale empathy was required. But, she said, to think with such an "enlarged mentality" in which "I can imagine how I would feel and think if I were in [another's] place" was the condition for sound moral judgment.

From its beginning, however, Nazism militated precisely against such a condition. Nazi terror compelled persons to identify only with like-minded Nazis. Authoritarian rule subordinated all thought to the narrow confines of the mind of the leader. And mass propaganda hounded persons into the mindset of a militant, racially pure herd. Arendt called this an "aura of systematic mendacity." Trumpism hasn't arrived at such extremes. But we can see all around an authoritarian spirit, mass propaganda and social media urging us down the road of refusing to consider the reality of another person. Duquesne University theologian Anna Floerke Scheid, in a recent powerful paper, has described this constellation of forces as "structures of sin with the capacity to harm individuals, communities, and nations."

The preeminent logic of intrinsic evil favored by "Faithful Citizenship" has almost nothing to say about these deceptive forces intent on making strangers of us all. Moral theology has traditionally held that lies are intrinsically evil. But this way of identifying the moral problem with lying says little about lying with an intent to harm persons, which is the aim, for instance, of mass propaganda. And, in any case, the intrinsic evils that preoccupy "Faithful Citizenship" pertain to reproductive and end-of-life issues.

For Arendt, to think in a way that refused to see the world from the perspective of another increased the likelihood of making no moral judgments at all. And that is in fact what happened. In Germany, in the first years after Hitler's rule began in 1933, she said, there was an "almost universal breakdown, not of personal responsibility, but of personal judgment" ("personal judgment" here refers to making basic decisions about right and wrong). This moral collapse early in the regime, she added, was "hardly perceptible to the outsider" but was nevertheless "like a kind of dress rehearsal for its total breakdown, which was to occur during the war years."

But what enabled people to resist this unfolding moral catastrophe? Arendt identified one thing that didn't help: A notion of conscience that emphasized obedience and law. In Germany, she had seen the conflation of morality and legality in an authoritarian key: The Fuhrer's words calling for the destruction of Jews became the law of the land; in turn, such civil laws requiring murder perversely were seen as the binding moral law as well. Moreover, she noted, it was by and large not those with a keen sense of obedience and commandment who resisted the general moral collapse. Rather, many simply exchanged a reflexive obedience to one set of commandments for a terror-stricken conformity to another.

Instead, Arendt argued, a different way of understanding conscience better helped to explain resistance to the moral collapse. Here she appealed especially to Socrates and his antinomian and individualist sense of conscience. Three things stand out. First, she said, the question to pose to those who heeded Nazi edicts was not, "Why did you obey?" but "Why did you support?" Insisting on obedience alone obscured the degrees of consent — the on ramps and off ramps — involved in participating in such an extreme political movement.

Second, she said, among those who resisted were the "doubters and skeptics" who were "used to examine things and to make up their own minds." Arendt prized those who rejected generic explanations and sanguine predictions and instead described precisely what was happening as the country morally collapsed.

Finally, she appealed to the Socratic notion of conscience in which a person, however much they go out into the world, always faces the choice of returning to oneself. For Arendt, those who resisted could not bear to return to oneself and find there the liar or murderer they may have become.

This logo appears on materials related to the U.S. bishops' "Faithful Citizenship" document that provides guidance to Catholic voters during a presidential election year. (CNS)

In "Faithful Citizenship," the bishops say they are not telling Catholics for whom to vote but they also specify that "the moral obligation to oppose policies promoting intrinsically evil acts has a special claim on our consciences." In effect, a Catholic is told your conscience is free to choose a candidate and then is told that your conscience is only free to choose a candidate in conformity with concerns about intrinsic evils voiced by "Faithful Citizenship."

Behind this suspicion of individual conscience is a longstanding conservative Catholic wariness of the subjectivist conscience. In this criticism, a permissive cultural liberalism inclines conscience to make judgments based only on the whim of my idiosyncratic feeling. In turn, I affirm my subjective truth at the expense of the moral truth founded on reason and common to me and to everyone else, too.

No doubt, the subjectivist conscience is a problem. But it's also a problem when conscience is seduced by the ideologies of intrinsic evil and the false absolutes of authoritarian religious nationalism. Arendt's reflections on the importance of the independent, Socratic conscience invite a renewed engagement in our time with what the Catholic moral tradition calls the "primacy of conscience." In this view, one is obliged to follow one's conscience while holding in tension what scholar Jesuit Fr. Frank Brennan aptly described as "the dignity and freedom of the human person, the teaching authority of the Church, and the search for truth and good."

The 'right to have rights'

Nothing in the U.S. in the last few years has evoked memories of the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 1930s more than Trump's oft-repeated claims that undocumented immigrants are "poisoning the blood of our country" and oft-repeated lies about legal immigrants like Haitian refugees in Springfield, Ohio. Moreover, he has put at the center of his presidential campaign the pledge to arrest 15-20 million immigrants (the U.S. government in 2022 estimated there are 11 million undocumented immigrants); detain them in camps; and deport them.

As a refugee and scholar, Arendt was intimately familiar with such speech and policy. Two lessons from her work about such matters especially stand out. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, she traced how one provocative step met by silence or subdued opposition led to another: First, the rhetoric of poisoning by Jews and others; then mass arrests; then vast internment camps; and finally industrial-level extermination. With each step, the Nazis tested the waters to see how far they could go. Before long, it was too late. To be sure, Bishop Mark Seitz of El Paso, Texas, and the Catholic Conference of Ohio (in response to the outrageous verbal attacks on Haitians in Springfield) have spoken out forcefully about such Trumpian rhetoric and policy but far too few other Catholic leaders have. Our immigration system is broken. Fixing it does not require mass dehumanization.

Arendt also insisted on the "right to have rights." As a moral claim, her concern about this arose from her assumption of the inseparable connection between having human rights and the right to belong to a community. "The calamity of the rightless," she said, is "... that they no longer belonged to any community whatsoever." For her, this connection not only underscored the social dimension of the person: rights belong to individuals-in-community. But it also pointed to the indispensable role of various communities — from the state to churches and more — in guaranteeing the rights of vulnerable persons in their midst.

For Arendt, to be stateless (like the undocumented of our time) was to be expelled from humanity and to be left to depend on the "unpredictable hazards of friendship and sympathy, or [on] the great and incalculable grace of love, which says with Augustine, 'Volo ut sis (I want you to be).' "

Here, I think, she points to a role for the church incompatible with the act-specific, culture-war approach of "Faithful Citizenship." Pope Francis speaks of such a role that proclaims the bond of dignity and community when, in Fratelli Tutti, he says, "Only a gaze transformed by charity can enable the dignity of others to be recognized and, as a consequence, the poor to be acknowledged and valued in their dignity, respected in their identity and culture, and thus truly integrated into society. That gaze is at the heart of the authentic spirit of politics." We see this gaze already heroically at work in the persecuted service of Annunciation House in El Paso and on the part of many others.

It is important to recall that the Catholic Church in Germany by and large saw in the rise of Nazi political power the opportunity to use state power to combat the liberal excesses of the Weimar Republic; to defeat communism; and to restore traditional Christianity. In its broad outlines, these are some of the same reasons culture war Catholics today are yearning for a Trump restoration.

Of course, Hitler later turned on the church and launched a terrible persecution. Many Catholics were martyred. But many Catholics served the regime in its unjust war. The German Catholic leadership had times of great heroism but also times of following the credo of the papal nuncio in Berlin during the war: "It is all well and good to love thy neighbor, but the greatest neighborly love consists in avoiding making any difficulties for the church." The work of Hannah Arendt can help us avoid such an heroic, ignoble, muddled fate.