A LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel) from the U.S. Coast Guard-manned USS Samuel Chase disembarks troops of the U.S. Army's First Division on the morning of June 6, 1944, (D-Day) at Omaha Beach. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Coast Guard/Chief Photographer's Mate (CPHOM) Robert F. Sargent)

Tomorrow will mark the 80th anniversary of D-Day, the allied assault on Normandy in World War II. The operation was codenamed Overlord. This will likely be the last major anniversary of the invasion at which veterans who participated in it will be present. The thought makes one sad. Those veterans are heroes, and we need heroes.

Across the years, it is still difficult for us to fathom the enormity of the undertaking. About 156,000 troops were hurled against Hitler's formidable Atlantic Wall, the largest amphibious operation in history.

Previously, during World War II, the Allies had mounted more or less successful amphibious operations in northern Africa and then Sicily. At Anzio, the most recent such assault, in January of 1944, the Allies were met with frustration. They landed the troops but instead of pushing inland, the commanders waited for the disembarkation of all the tanks and trucks intended to transport the troops in the weeks ahead. Fourteen days after the initial assault, there were 18,000 vehicles within the beachhead, serving some 70,000 troops. In a peevish telegram, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill telegraphed the commander: "How many of our men are driving or looking after eighteen thousand vehicles in this narrow space? We must have a great superiority of chauffeurs." The failure at Anzio hung over the final planning stages of Overlord.

When he became prime minister of the United Kingdom in May 1940, Churchill had given himself the additional title of minister of defence. The duties, and authority, of the new post were unspecified, and therefore vast. He was far more heavily involved in detailed war planning than his American counterpart, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

One of my favorite stories from the entire war had to do with a planning meeting for Overlord. The generals were debating the precise time to launch the invasion, at high tide or low, in the morning or later in the day, etc. "They were arguing back and forth, back and forth, what should be done," according to U.S. Admiral Alan Kirk, chief of U.S. Naval Operations for the assault. "Finally Mr. Churchill lost patience, and he smote the table and said, 'Well what I would like to know is, when did William cross?' The accused stood mute. No one could remember. He was obviously talking about William the Conqueror. Finally Pug Ismay [Churchill's military staff officer], standing behind Mr. Churchill, coughed into his hand and said, 'Sir, I think it was 1066.' " No one could offer more precise information.

The story is hilarious in retrospect, but it also points to an astonishing historical fact. No one had forced the channel since William had done so almost 900 years prior. William had not had to face the armed might of Nazi Germany when he landed.

Advertisement

We all know the general outlines of the battle. On four of the five landing beaches, the Allied troops made quick work of the German defenses but at Omaha, they encountered fresh troops and the fighting was ferocious. An estimated 6,000 Americans were killed, wounded or missing by the end of the first day, and none of the intended objectives had been reached. But the American, British and Canadian troops had managed to secure the beachheads and push a little inland. They were aided by the work of French partisans.

In the days that followed, all five beachheads would be linked, and supplies began to come through the two artificial harbors that had been towed from England and sunk along the Normandy coast. The artificial harbors, codenamed Mulberrys, had been one of Churchill's most important ideas because the allies would not capture the major port of Cherbourg until June 26, 1944, and by then the harbor had been systematically trashed by the Germans.

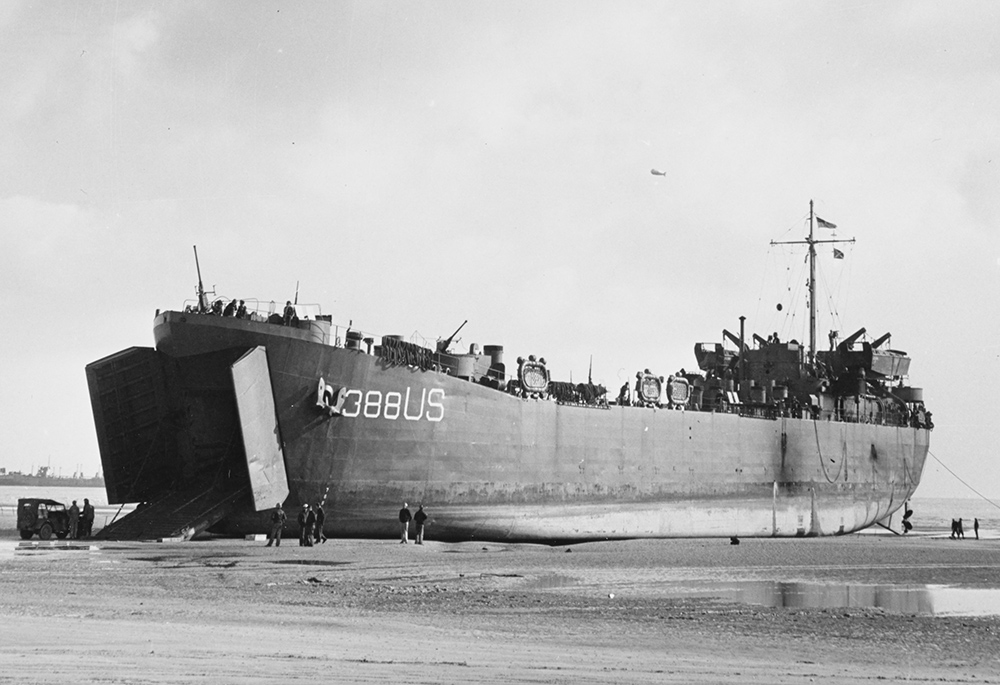

USS LST-388 unloads on a Normandy beach at low tide on June 12, 1944. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Navy Photograph/Combat Photo Unit Eight (CPU-8) )

On the night of June 6, 1944, President Roosevelt addressed the nation by radio. His speech consisted mostly of a prayer:

Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.

Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith.

They will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph …

And, O Lord, give us Faith. Give us Faith in Thee; Faith in our sons; Faith in each other; Faith in our united crusade. Let not the keenness of our spirit ever be dulled. Let not the impacts of temporary events, of temporal matters of but fleeting moment let not these deter us in our unconquerable purpose.

With Thy blessing, we shall prevail over the unholy forces of our enemy. Help us to conquer the apostles of greed and racial arrogancies. Lead us to the saving of our country, and with our sister Nations into a world unity that will spell a sure peace a peace invulnerable to the schemings of unworthy men. And a peace that will let all of men live in freedom, reaping the just rewards of their honest toil.

Thy will be done, Almighty God.

Amen.

Here is Christian nationalism done right: Petitioning, inclusive, noble, heartfelt.

Our culture has developed in its views of war. One of my favorite World War II movies is the 1962 film "The Longest Day" which catalogues the fight for Omaha Beach as well as the travails of airborne troops dropped near the vital crossroads town of Sainte-Mère-Église. It conveys the violence of the fighting, but in a fleeting manner, without much of the intense and relentless gore war entails. In 1998, Steven Spielberg's "Saving Private Ryan" opened with a 24-minute sequence cataloguing the first assault. That sequence captured, and did not merely convey, the violence of war.

This year, as we reflect upon the fact that the last soldiers who fought that day will soon join their comrades who died that very day, it is good to be horrified by that violence. It is good, too, to be grateful to those who braved it in order to liberate France and all of Europe from the Nazi tyranny. It is difficult to conceive of the ordeal they faced 80 years ago and of the courage that was required, but they faced it. All peoples who value freedom and democracy owe them a debt that can never be repaid.