"Saint Augustine" by Antonio Rodríguez, Spanish, 1636-1691 (Artvee)

The quadrennial party conventions leave many of us exhausted with politics and political coverage. The endless analysis, always focused on what divides. The late nights churning out columns once the speeches are done. The absence of any other news is especially bad for us in the Catholic press because everything at the Vatican shuts down in the summer.

This year, there is a tonic at hand: Tomorrow is the feast of St. Monica and the day following is the feast of her son, St. Augustine. And so it is that I find myself pouring over my dog-eared copy of a wonderful book by the late Jean Bethke Elshtain, Augustine and the Limits of Politics.

Elshtain's book is remarkable in many ways, but especially in her ability to bring some of the key concepts Augustine used to explain politics to bear on the very different political realities of our time. Democracies are not empires, modernity is not antiquity, class structures have changed entirely, but the human heart remains the human heart. And few theologians in the Christian tradition wrestled with the enigma that is the human heart with greater insight than Augustine.

We Americans are fiercely independent. Our national holiday is called Independence Day. Consumer culture reinforces our instinct to autonomy: With credit card in hand, we can choose which of a dozen detergents with which to wash the many clothes we have worn. Our menus present a range of options to satisfy our appetite. How many vodka brands are there? How many brands of cars and flavors of doughnuts from which we get to make our choices?

Augustine, instead, emphasizes our dependence. Elshtain observes:

False pride, pride that turns on the presumption that we are the sole and only ground of our own being; denying our birth from the body of a woman; denying our utter dependence on her and others, to nurture and tend us; denying our continuing dependence on friends and family to sustain us; denying our dependence on our Maker to guide and to shape our destinies, here and in that life in the City of God for which Augustine so ardently yearned, is, then, the name Augustine gives to a particular form of corruption and human deformation. … Those who refuse to recognize dependence are those most overtaken by the urgency of domination … Every "proud man heeds himself, and he who pleases himself seems great to himself. But he who pleases himself pleases a fool, for he himself is a fool when he is pleasing himself," Augustine writes [emphasis in original].

Book cover to Augustine and the Limits of Politics

Here is a lesson for everyone who reduces their own view of the world to the whole, for whom univocal approaches are to be preferred, and to whom monocausal explanations make sense. Augustine recognizes the epistemic limits of all human endeavors, but in politics, where power and domination are the name of the game, these habits of mind are especially treacherous. We, all of us, live and form our opinions and make our decisions in a fallen state. Sin beclouds our judgments.

The Christian nationalist finds in Augustine a sure barrier to his objectives. Augustine repudiated perfectionism. "If one brings the city of God into too tight a relationship to the city of man, then the latter begins to make claims that take on the character of the ultimate." In Milwaukee last month, Donald Trump's religious adherents portrayed him as divinely spared from an assassin's bullet, that he may lead the nation to the promised land. In Chicago last week, there was easy talk about "joy" but the wise person seeks joy where joy may be found and very few people, certainly those citizens who are largely disengaged and suspicious of elites, look to politics as a source of joy. They are not wrong.

Advertisement

Augustine points to a different source of what we would call social solidarity: human fellowship and friendship. Augustine found Scipio's definition of the commonwealth in Cicero's On the Republic inadequate. Elshtain observes, "Cicero makes a 'vigorous and powerful argument on behalf of justice against injustice,' but if one ardently seeks justice, one requires a more expansive set of human possibilities that simultaneously humble us, yet draw us into care for our earthly city. For our ties to the earthly city are strong, resilient, tenacious."

Elshtain continues:

This is where love comes in — love of God and love of neighbor — and this is where justice enters as well. Augustine's alternative definition [of the commonwealth] starts with love. "A people is the association of a multitude of rational beings united by a common agreement on the objects of their love." It "follows that to observe the character of a particular people we must examine the objects of its love." No single man can create a commonwealth. There is no ur-Founder, no great bringer of order. It begins in ties of fellowship, in households, clans, and tribes, in earthly love and its many discontents. And it begins in an ontology of peace, not war.

There is a lot to unpack there, but for the moment, it is enough to point out that culture is the realm where meaning is imparted and common loves are discerned, and only derivatively in politics. And the further one moves into the realm of politics, the allures of power and dominion make their presence felt in ways that frustrate both love and justice. This is the human condition.

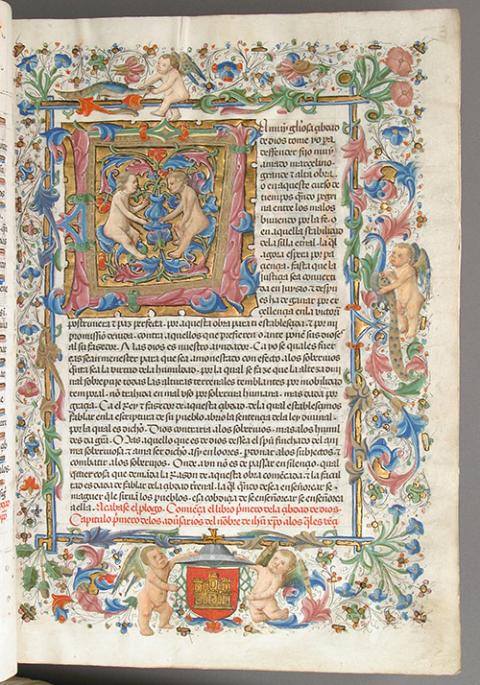

Spanish translation of St. Augustine's City of God by Cano de Aranda (Museum Accession/Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Fall did not only bring sin into the world. It brought death. In re-reading Elshtain I had forgotten that early in the book, she turns not to The City of God, but to The Confessions to highlight Augustine's understanding of human friendship, and not to its presence but to its absence. Recalling the death of his boyhood friend, Augustine writes:

My own country became a torment and my own home a grotesque abode of misery. All that we had done together was now a grim ordeal without him. My eyes searched everywhere for him, but he was not there to be seen. I hated all places we had known together, because he was not in them and they could no longer whisper to me "Here he comes!" as they would have done had he been alive but absent for awhile. … Tears alone were sweet to me, for in my heart's desire they had taken the place of my friend.

I confess that when I first read The Confessions in college in the early '80s, that passage did not make an enormous impression on me. By the end of the decade, in the full horror of the AIDS epidemic, those words became a powerful companion. The horror of death is its abysmal loneliness, the fact that a relationship upon which we depend can be ended and ended utterly. There is no political program that can overcome that horror. Here is the final barrier to politics' claim to any ultimate sense of loyalty or commitment.

Politics is exciting and consequential. I love writing about it. But it has its limits. As we Catholics prepare to celebrate the feasts of Monica and Augustine, and recover from this whirlwind of political activity and look ahead to two more months of it, it is good to keep those limits in mind.