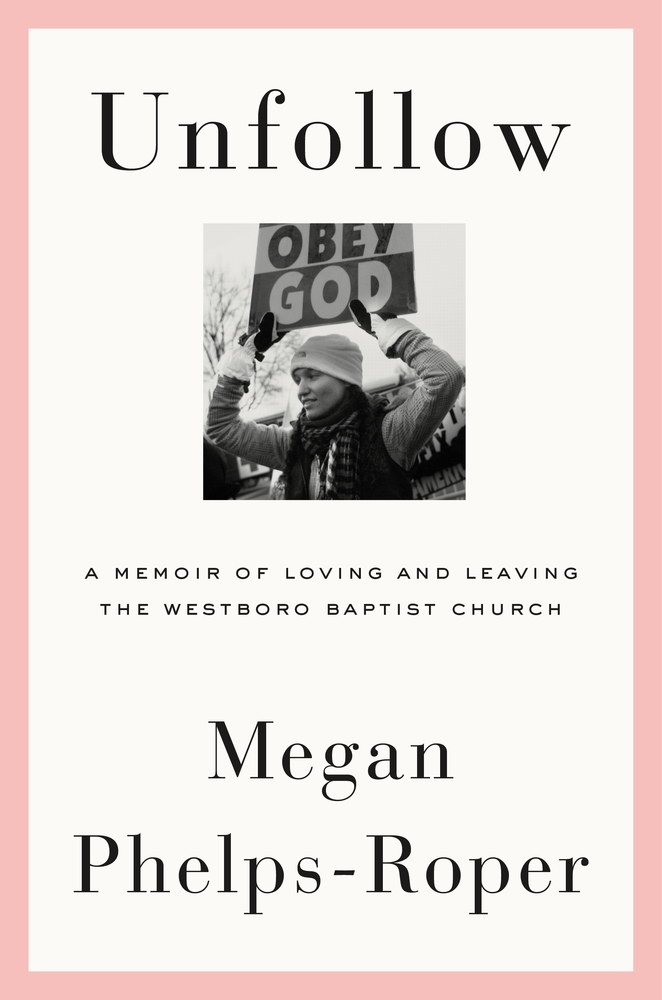

A sign at the Westboro Baptist Church in Topeka, Kansas (Flickr/Tony Webster, CC by 2.0)

Starting with Oregon in 1997, voters in nine states and the District of Columbia have approved "Death with Dignity" laws. Other state legislators are debating the issue or will be soon.

The question of physician-assisted suicide informs Diane Rehm's sobering new book, When My Time Comes: Conversations About Whether Those Who Are Dying Should Have the Right to Determine When Life Should End, which consists mostly of interviews with individuals who have had experience with end-of-life care — as she herself did.

In a preface, the 83-year-old Rehm (retired host of NPR's "The Diane Rehm Show") vividly recalls her mother's harrowing death in 1956 of cirrhosis of the liver. Years later, Rehm's first husband, who suffered from Parkinson's disease, died essentially by starving himself to death because his physician was forbidden by Maryland law to help him die. Both deaths influenced Rehm's perspective favoring physician-assisted suicide.

This book (which also has a documentary that will soon air on public television) is one of several recently published concerning right-to-die laws. It includes talks with priests, lawyers, physicians, terminally ill individuals, those whose loved ones have died either with or without physician assistance, and others. Most agree with Rehm's position.

One of the most affecting interviews occurred with Dan Diaz, widower of 29-year-old Brittany Maynard, who in 2014 died of a brain tumor with physician assistance. Maynard, whose tumor caused grand mal convulsions, moved from California to Oregon to take advantage of Oregon's (first in the nation) Death with Dignity Act.

Rehm also interviews gerontologist Christina Puchalski, head of George Washington University Medical School's Institute for Spirituality & Health, as well as Fr. John Tuohey, formerly a college professor and ethicist for a Catholic health care system. Puchalski advocates for more compassion towards the dying but doesn't explain how harried hospital workers can find the time to do this.

(Unsplash/Bret Kavanaugh)

Tuohey, whom Rehm calls, "firm in his Roman Catholic beliefs," explains the church's stance on "the grave sin" of physician-assisted suicide and argues that God is the author of life and is consequently the only who has the right to end life. Doctors can provide palliative care, he says, to manage pain even if that care sometimes causes death. His account is somewhat convincing, but I felt as though he were splitting hairs.

Although Rehm disagrees with Tuohey, she interviews him respectfully, listening to his views and to those of everyone in the collection. All of which suggests that perhaps one of the most valuable parts of the book is its balanced approach to a polarizing topic. I also appreciated the thought-provoking perspectives of the contributors.

One of them, the author and lawyer John Grisham, who has said in a separate interview that he has very strong religious convictions which he keeps to himself, favors physician-assisted suicide. But he goes even further stating that he believes it's immoral to keep a brain-dead person alive by machines.

Grisham advocates for a living will and advanced directives. He also notes that although a family discussion about death is a difficult one, it is a necessary one.

In this absorbing biography, Peter Feuerherd, news editor for the National Catholic Reporter, convincingly argues that the Roman Catholic Church's recent history is a "complicated, disheartening mess."

There's the number of rank and file Catholics hemorrhaging from the church, a lack of converts, clericalism, a dearth of religious vocations, the closing of Catholic schools and churches, financial scandals in the Vatican, and the sex abuse scandal, as well as huge financial losses resulting from sex abuse lawsuits.

But perhaps the worst problem is that many bishops covered up the wrongdoing of priests, other bishops, and even cardinals — like ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who was removed from public ministry in June 2018 because of sexual abuse allegations.

In The Radical Gospel of Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, Feuerherd chronicles some of the difficulties besetting the contemporary church and the response of Gumbleton, auxiliary bishop of Detroit, to those challenges.

Retired Auxiliary Bishop Thomas Gumbleton of Detroit holds the Eucharist during the funeral Mass for Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan May 6, 2019, at the Church of St. Francis Xavier in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. (CNS photo/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Gumbleton, Feuerherd insists, is "different" from many Catholic bishops because he followed his conscience, as opposed to the program set out for those who would ascend the ecclesiastical ranks.

He spent most of his active priesthood working against corruption in the church, and as a corollary, he tried to console those who had been abused by priests. He worked with Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan and the peace movement, later questioning the just war theory and the morality of nuclear weapons. He also encouraged those who advocated for women in the priesthood.

Born in 1930 in Detroit, Michigan, Gumbleton grew up in a traditional, devout Roman Catholic family. He, like many young Catholic males of the time, attended a Catholic elementary school and then entered a high school seminary. In 1952, he received his Bachelor of Arts from The Sacred Heart Seminary and was ordained to the priesthood in 1956.

Gumbleton was named a bishop in 1968 by Archbishop John Francis Dearden, who told him to "Just be yourself." As Feuerherd describes it, Gumbleton took the counsel of his mentor to heart. Translated, this meant that Gumbleton was honest even though his perspective wasn't necessarily approved by his superiors in the church, as when he asked the Ohio Legislature to extend the statute of limitations on sex abuse cases; disclosed that he had been abused by a priest in the junior seminary; and revealed that his brother Dan was gay.

Laden with events spanning about 60 years, Feuerherd's book contains names, dates, places and circumstances that many may have read about but have probably forgotten. A timeline would have helped a reader to keep the facts straight. This is especially true when one considers that Feuerherd essentially tells two histories, that of the church both today and in the latter half of the 20th century, as well as that of Gumbleton caught in the center of this maelstrom.

Yet this is a quibble. Most Catholic readers won't want to put the book down.

Everyone called Fred Phelps "Gramps." The pastor of the Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) and head of the family law firm, Phelps was considered a warm, generous man. But when his granddaughter, Megan Phelps-Roper, left the church, she saw another side to him. That's the trajectory of Phelps-Roper's disquieting Unfollow: A Memoir of Loving and Leaving the Westboro Baptist Church, which tells the story of the ill-effects of religious belief gone awry.

A dedicated member of the Westboro Baptist Church, Phelps-Roper grew up in Topeka, Kansas. Her family and everyone she loved belonged to the church. Her life revolved around church activities. At five, she joined the picket line protesting groups thought to be sinners.

She remembers her grandfather's fire and brimstone sermons, which were highly regarded by his congregation — most of whom were members of his own family. His beliefs were influenced by the teachings of John Calvin, especially his doctrine on grace. Phelps-Roper references her grandfather's sermons and their emphasis on God's anger, which reminded me of "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," by the British colonial preacher, Jonathan Edwards.

Starting in the early 1990s, she explains, the church was notorious for hurling insults against gays and lesbians, Muslims, and Jews, as well as celebrating tragedies like 9/11, AIDS, and the deaths of soldiers. Phelps-Roper saw the viciousness of the Westboro Baptist Church protests, especially when church members celebrated the horrific West Nickel Mines and Sandy Hook school massacres. Later she also caught the WBC doctoring videos and altering the truth.

She questioned her mother, Shirley Phelps, about the appropriateness of these actions. One of Fred Phelps' 13 children, Shirley explained that the members of the church wanted to save souls. She also said that although people could never know if they were among the elect, it was a good sign if they rebuked sinners.

But Phelps-Roper, who had questioned the validity of predestination and other Westboro Baptist Church teachings, began to doubt her mother's explanations. She also had doubts about other tenets of the WBC and especially wondered about its belief that its teachings were the only correct ones.

Advertisement

She spends much of the book considering the rationale behind the Westboro Baptist Church's activities and references numerous Bible quotes both for and against the church's positions. Unfortunately, she tends to interpret the Bible literally and seldom cites book, chapter and verse, making it difficult to verify the quote or the context. But her analysis of the Westboro Baptist Church seems spot-on.

Besides reflecting on the Westboro Baptist Church and its views, Phelps-Roper reminisces about her relationship with her mother, father, and 10 siblings — several of whom had earlier left the WBC and had therefore been ostracized, another circumstance that worried her.

But ultimately, it was her work on social media proselytizing for the Westboro Baptist Church that played the major role in her decision to leave her church, as people she met on Twitter challenged her to rethink her religious beliefs. They did so not by hurling insults as members of the Westboro Baptist Church had done to those with whom it disagreed — but by treating her kindly.

[Diane Scharper has written seven books. She is an instructor for the Johns Hopkins Osher program where she teaches memoir and poetry.]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.