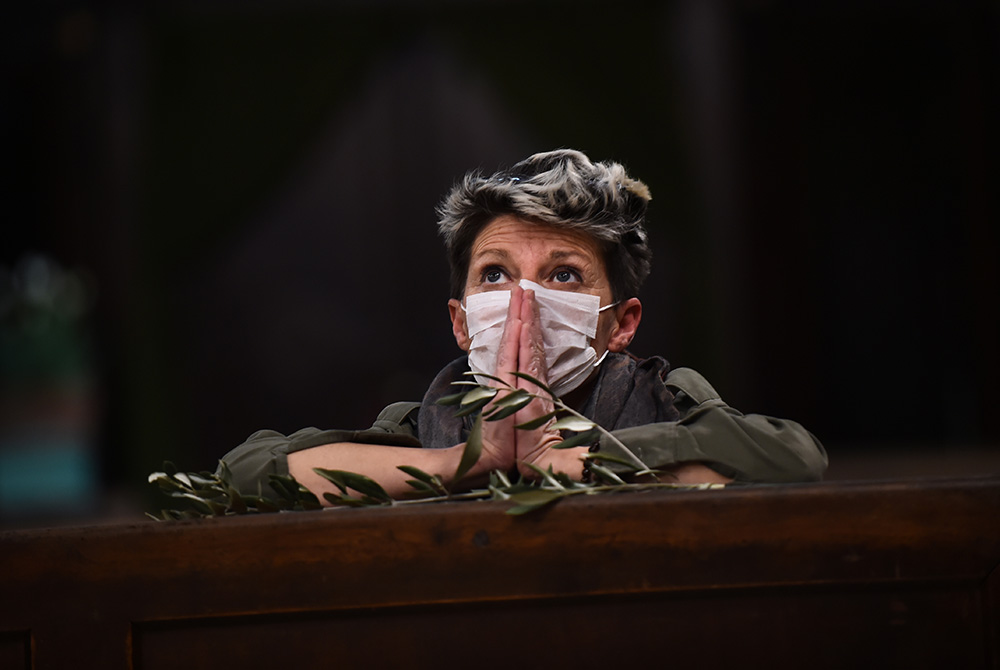

A woman wearing a protective mask due to the coronavirus pandemic prays inside the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus on Palm Sunday, April 5 in Turin, Italy. (CNS/Reuters/Massimo Pinca)

"Rules are not necessarily sacred," Franklin Delano Roosevelt said, "principles are."

One thing is clear: "Rules" are not getting us out of the largest pandemic in modern history.

We're washing our hands and wearing our masks and staying indoors and counting the number of people in every group, but the numbers keep going up regardless.

At the same time, principles, if any, may be necessary but nobody talks about them much —despite the fact that it's principles that guide our behavior or help us to evaluate what's going on around us. Principles are the motivating force upon which everything we do is based.

Worse, if we never ask ourselves what our principles really are, how can we ever survive, let alone resurrect the foundations of a moral, an effective society, tumbled by circumstances, felled by the deaths of the past. How can we ever change what must be changed?

That kind of spiritual ignorance is no small factor in the shrinking of the soul of a country.

Surely we must insist on asking ourselves the question: what's operating in us — and what isn't — that could have/would have stopped this thing weeks ago? If the rules aren't working, what principles, if any, are driving us?

Those questions plague me daily now. And here's why.

The Benedictine Order, my community's tradition, is the oldest religious order in the church. Which means that in its over 1,500 years of existence, it has lived through every plague, epidemic and pandemic in the Western world: smallpox, the Black Death, cholera, yellow fever, the Spanish flu and HIV/AIDS to name a few. And there's not a single word in that ancient document that alludes to what history told us we needed to do when the next epidemic might rear its hoary head. No rules about it at all.

In fact, come to think about it, there are no real "rules" about much of anything in the "Rule of Benedict."

But, at the same time, there are principles aplenty.

YouTube video from EWTN

Having read the Rule every day for over 65 years, they have been drip, drip, dripping into my soul to the point that I am beginning to see the power of principles over proscriptions very clearly.

The question is what kind of basic truths — principles — must drive us if we are to endure and survive the kind of despair that threatens a national moment like this one? Here we are at the touchdown point of a tornado called a pandemic. Everything about life before this has been wiped away. Worse, we have not a hint of what our world will look like in the future. Unless we define the principles we need to preserve, not only to get us through this moment but to prepare for all the great moments in times to come, this will all have been for nothing.

After 1,500 years, four principles of life stand in striking contrast to what a casual observer might consider the pillars of an ancient Benedictinism that for all this time has apparently remained as fresh and alive as tomorrow. Why? Because they stretch the soul to become more than it is, whatever period of history we're in.

First, the Rule says in Chapter 52, "Let the oratory be what it is called." No one can get through life — or a pandemic — unscathed who has not daily returned to the sacred space of the heart where the energy flows from the God of life to our own.

Becoming a spiritual person is what raises us above the angst of life. We can lose anything, let anything go, begin again after whatever tornado shreds us if we only learn to live with one part of the human heart daily invested in the presence of the divine. In that sacred space within, we seek the strength it takes to respond rightly to the pressure of such pain. We are not pleading for magic from a vending machine God to save us from its inconvenience.

Second, Chapter 35 gives one clear direction: Benedict writes: "The members should serve one another. ... Let those who are not strong have help so that they may serve without distress and let everyone receive help as the size of the community or local conditions warrant."

We take on the challenges of the community — the masks and distancing and overtime work that's needed — as if they were our personal responsibility alone. We check on those who are frail, who need to know they're not alone, who are seeking services. We allow no one to be out of contact. We volunteer where we're needed.

A man in Oakland, California, waits for a bus April 6 during the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS/Reuters/Shannon Stapleton)

Third, in Chapter 50, Benedict does what most people would least expect. After writing chapters on community prayer and the choral recitation of the Divine Office, he suddenly writes, "Members who work so far away ... are to perform the Opus Dei — prayer — where they are."

There are some things so important to the life of the human community that we may not use holiness as an excuse not to do them. What the world needs us to do is what will make us holy at the same time. We do not hide behind prayer as an excuse to care only for ourselves. It is precisely all the hours we spend in prayer that makes it possible for us not to be there sometimes.

Finally, The Dialogues of St. Gregory the Great, a hagiographical biography of Benedict, teaches us our fourth principle in a story. Gregory writes about the man who in hard times came to the monastery to beg for oil. Oil was the staple of the time: It gave light and provided heat in bad weather, made food preparation possible and could even provide the beggar an opportunity to earn a little money if he could sell some of it.

The business manager of the monastery, however, a careful businessman, knew how important oil was to the monastery itself, and — since anything could happen — refused the beggar the oil.

When Benedict, the visionary leader, heard what he had done, he told the business manager to bring the vial of oil and summoned the entire community. When all had assembled, he took the oil from the business manager, handed it to another monk and told him to throw it out the window. Point made, he directed a third monk to bring the vial in again and present it to the beggar.

Then, when Benedict knelt down to pray, the half-full vial of oil began to overflow.

Advertisement

The principles of the holy life are obvious: it begins with a sterling spirituality, an abounding love of community and an incessant sense of personal responsibility that makes the undoable, doable always.

Until finally, it depends on following leadership that glows with goodness and vision. It is the leadership that shows us all how to be more empathic, more aware of the needs of others, more present to the demands of it all. It is the living vision of moral leadership that sends us back into the wind as long as it rages. It brings us to a greatness no circumstances can exhaust, no storm can conquer.

Indeed, it's not the "rules" that count; it's principles that are the driving force. Principles are the noble base. Principles are the foundation of character of our souls and the quality of our lives.

From where I stand, it's not about the rules. It's about the heart. Then we can go on, and go on, and go on. For over 1,500 years. Same rule, same principles, same gratuitous generosity of life.

[Joan Chittister is a Benedictine sister of Erie, Pennsylvania.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Joan Chittister's column, From Where I Stand, is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page to sign up.