Image of anastasis, or Resurrection, inside of Chora Chuch Mosque Museum, in Istanbul, Turkey (Sarah Sexton Crossan)

One of the great tragedies of Christianity is the continued divide between the Eastern and Western churches. Popes and patriarchs often meet to discuss the dissolution of this partition, but there is still parochialism, suspicion and feelings of theological superiority on both sides that deprive us of the richer faith that could be found in our shared love of Christ.

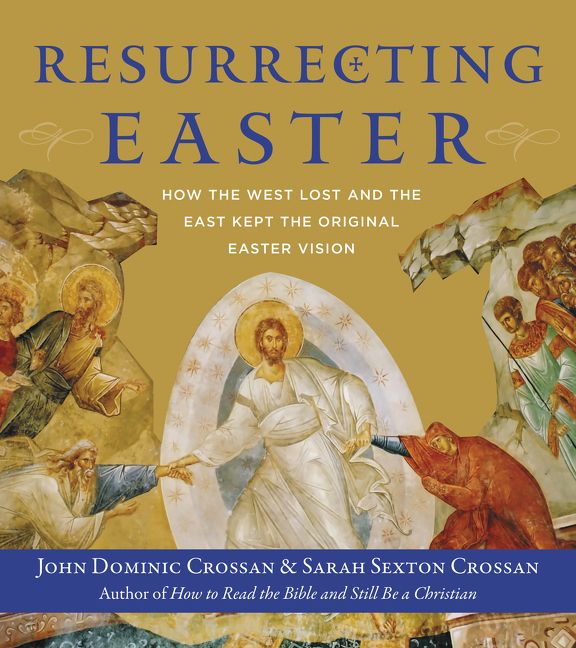

Resurrecting Easter: How the West Lost and the East Kept the Original Easter Vision, brings the East and West a step closer together. The authors, John Dominic Crossan and Sarah Sexton Crossan, do this by showing us visual theological expressions of our mutual Christian past. They share with us specific elements of image and Scripture that can lead to a fuller understanding of what Christ's resurrection means to all of humanity.

The book is a mix of travelogue, art history, church history and theology, as the authors examine ancient images of Christ's resurrection in both the East and the West. The Crossans are helpful tour guides who offer the reader magnificent images and thought-provoking commentary. Sarah is a veteran photographer and visual artist. John is author of more than 20 books, a professor emeritus at DePaul University and a noted biblical scholar whose portrayals of the historical Jesus have often been controversial.

This project developed out of the Crossans' curiosity about an engaging image of the Resurrection in an 11th-century Cappadocian church. Unlike the lone figure of the triumphant Christ generally seen in Western churches, this icon in Turkey showed Christ surrounded by others. This led them to question why Western Christianity depicts an individual resurrection of Jesus, whereas Eastern Church icons show a universal resurrection for Jesus and all humanity together.

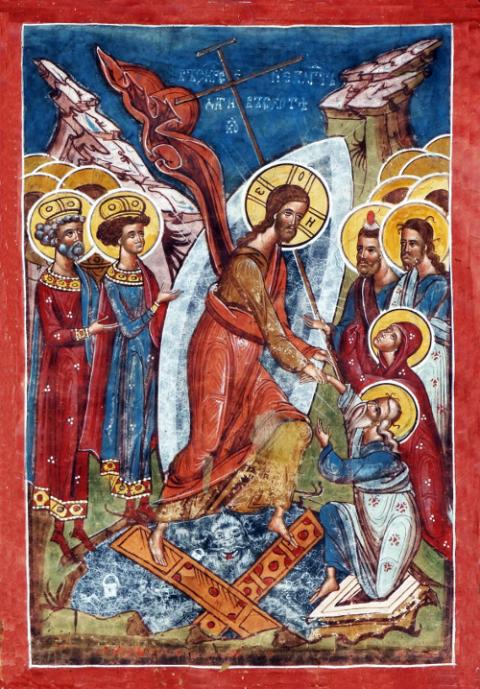

Image of anastasis, or Resurrection, outside of the Church of St. George at the Voronet Monastery in Gura Humorului, Romania (Sarah Sexton Crossan)

This question set off a quest that ranged along Byzantium's Greek Tiber, the Syriac Tigris, the Russian Neva and the Coptic Nile. The duo made 20 research trips over the course of 15 years to document images and collect information about extant versions of Christ's resurrection, although the authors prefer to use the Greek word anastasis, which literally means "up-rising."

According to John's commentary, "These images are quite simply visual theology, and they challenge verbal theology to explain them — if it can."

In his own efforts to explain these images, Crossan asks evocative questions about the nature of Christ, the purpose of his death and resurrection and what those things ultimately mean for human existence and salvation. He explains that the book's emphasis on universal over individual iconography for Christ's resurrection is "remedial education for us Western Christians."

The common Western image of the Resurrection shows Christ as a triumphant yet singular figure. If other humans are present at all, it is often as guards lying asleep by the tomb. Crossan asserts that the image of a solo, triumphant Christ does not tell the entire story. It does not express the cosmic enormity of the cross and Resurrection in relation to human life.

Advertisement

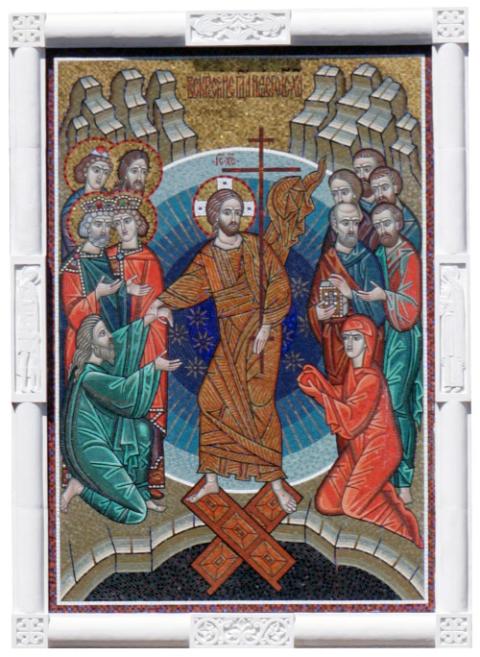

The common Eastern icon of the anastasis shows Christ breaching the gates of hell, generally with two long, broken gates lying in the shape of a cross and a personified Hades or Satan lying conquered under his feet. The key element in this icon is Christ firmly grasping the wrist of Adam in the pit, pulling him along as he ascends into heaven. Eve is almost always represented, too, and sometimes she is also shown being pulled upward by the hand of Christ. David, Solomon, John the Baptist or various others are sometimes in view. In all versions, it is clear that Christ has conquered Hades and is rescuing the souls imprisoned by death.

The authors begin the sixth chapter of the book with a quote from the "Paschal Homily of St. John Chrysostom." This work, written around the late fourth or early fifth century, is joyfully read at the end of every Orthodox paschal liturgy. Only a snippet of the sermon was provided in the book, but a longer bit provided here supports Crossan's argument regarding the universality of Christ's resurrection:

Let no one mourn that he has fallen again and again; for forgiveness has risen from the grave. Let no one fear death, for the Death of our Savior has set us free. He has destroyed it by enduring it. He spoiled Hades when he descended thereto. He vexed it even as it tasted of His flesh. … It is vexed; for it is annihilated. It is vexed; for it is now made captive. It took a body, and it discovered God. It took earth, and encountered Heaven. It took what it saw and was overcome by what it did not see. … Christ is risen, and the tomb is emptied of the dead.

Image of anastasis, or Resurection, on Resurrection Gate, inside Red Square, in Moscow, Russia (Sarah Sexton Crossan)

Crossan asserts that the image of the universal Resurrection is the more theologically accurate portrayal of Christ's resurrection and uses his considerable knowledge of scriptural history to support this. This book may well stir some surprise or controversy among Roman Catholic Christians. However, Eastern Orthodox readers may breathe a sigh of relief and simply say, "Finally!"

The fact that the Crossans can present their images and analysis as something new for Western readers shows how far apart Eastern and Western Christianity still stand. An icon of the anastasis can be found in every Orthodox Church throughout the world, so there is no need for the curious to travel far.

Even though the Crossans "discovered" what has been lying in plain sight, their work is valuable because it brings Eastern and Western theology into dialogue via accessible commentary and fascinating images. The authors remind the Latin faithful about what Orthodox believers have embraced for centuries: Christ's resurrection was a universal, communal event. It was not for the sake of stunning us with his divine glory, it was so we — the new Adam and Eve created in God's image — can rise and live fully in the light of divine goodness.

[Melissa Jones is an adjunct professor of liberal studies at Brandman University in Irvine, California. Her doctoral studies examined the influence of Augustine on Russian Orthodox thought.]