Masks in hand, Dr. Jennifer Avegno, front row, second from left, and her family pose together in September: husband Kurt Weigle and children, from left, Lucy, 15, Gigi, 11, Eva, 14, and Joey, 17 (Provided photo)

On July 20, 2018, two months after her inauguration, Mayor LaToya Cantrell of New Orleans appointed Dr. Jennifer Avegno as city health director.

Avegno, 47, was a seasoned emergency room physician and professor at Louisiana State University School of Medicine in the city. She created and was director of the Division of Community Health Relations & Engagement at LSU Emergency Medicine focused on improving disparity-driven outcomes across New Orleans. A graduate of the all-girls St. Mary's Dominican High School, she grew up with seven younger siblings, all adopted, three of whom, mentally disabled, died young. In 1993, Avegno graduated from the University of Notre Dame with a bachelor's degree in sociology; she returned to New Orleans to earn a master's degree in sociology at Tulane University, focusing on urban poverty, then shifted to LSU for medical school, sailing through.

When her new job was announced, political insiders yawned. The job was a black hole. How many voters can name the health director?

Most of the department's 100 staffers do research for grant proposals that yield 90% of the $24 million budget, less than half the $55 million it was in 1996 when Dr. Brobson Lutz's tenure ended.

"The office has been severely downgraded," Lutz, an internist, told NCR.

"It no longer runs primary clinics, does child immunizations or has field agents enforce health code standards. It's all been outsourced to the state. The farming out of responsibilities began with [President Ronald] Reagan cutting the federal budget on preventive health services. We're lucky to have a health department."

As a young emergency room physician, Jen Avegno treated gunshot wounds, drug overdoses, and trauma cases from accidents and beatings while the bloated state medical bureaucracy produced long wait-times for poor folk seeking basic care at hospitals instead of clinics or physicians' offices. Once Avegno ordered a battery of tests for a Black woman complaining of stomach pains; she was diagnosed with advanced cervical cancer, which a primary care visit could have caught early on.

Appalled by the systemic waste, Avegno submitted her resume to the mayor-elect's search committee and sat for an interview. When the job offer came, she thought, "God is telling me, take the chance." The position allows her to continue emergency room work.

Dr. Jennifer Avegno (New Orleans East Hospital)

"My faith life helps me support patients in their time of crisis," she told NCR. "When people mention God — often timidly — and find reassurance by their doctor, they open up and put their trust in me. If I sense that religion or faith is important to one of my patients, I try to mention God in some form. It generally brings a deeper dimension to the traditional doctor-patient relationship."

Her favorite saint is St. Luke, patron saint of physicians, but she also asks St. Thomas Aquinas for wisdom and St. Dominic for assistance in speaking the truth.

"In a world where religion is often taboo, I find that so many in New Orleans — a deeply spiritual town — want to have their faith lives supported in moments of great fear," she said.

Avegno has three children from her first marriage, and a stepchild with her husband of four years, Kurt Weigle, president and CEO of the Downtown Development District. Two of their kids are altar servers.

In early March, after weeks of consultation with local colleagues and national authorities on preparing for the coronavirus, Avegno studied the files on the first three COVID-19 cases in New Orleans — none traceable to Wuhan, the epicenter in China. That meant the virus's lethal tentacles starting to squeeze New York City lay coiled in her hometown.

Avegno knew that the only solution was a shutdown. She gave the mayor and several advisers a grim briefing. The mayor said: "We have to cancel this weekend's parades."

Avegno took it as a good first step.

Mardi Gras was over Feb. 25; the spring season of festivals and parades, rooted in the ethnic folkways that typically sends rivers of money to bars, restaurants, hotels, music clubs and small vendors, loomed as a gigantic boarding house, primed for COVID-19 virions.

Advertisement

On Monday, March 9, Cantrell flanked by Avegno and three other officials, cancelled the weekend schedule for Irish, Italian and Black parading clubs. Five days later, on seeing footage of a sprawling block party outside an Irish Channel bar, the mayor sent police to disperse crowds for being "irresponsible, potentially endangering the entire community."

After a reactionary radio deejay attacked the mayor, Avegno worried about inflamed public reaction. "San Francisco had just begun its shutdown," she told NCR. "The concept was so radical. We had few cases but clear data projections. Italy and France had shuttered their cities. But doing it sure felt scary."

Heeding Avegno's advice, a day after cutting restaurant and bar hours, Cantrell ordered the closure of bars, nightclubs, casinos, movie theaters, malls and gyms, ending dine-in service at restaurants and issuing guidelines for other businesses with a call for social distancing. Gov. John Bel Edwards, a centrist Democrat, issued similar closure orders, drawing flak from Republicans in a President Donald Trump-majority state.

By March 18, New Orleans had 280 coronavirus cases, the nation's third-highest per capita rate. Obsessed with flattening the curve, Avegno worried over a public health impact from the Stay Home Mandate, issued March 20.

"Would violence increase? Would people go hungry, or stop spending on medical care and other essentials and die of preventable diseases? Stimulus checks and expanded unemployment coverage were not on the table then. We were making emergency policy with no back-up."

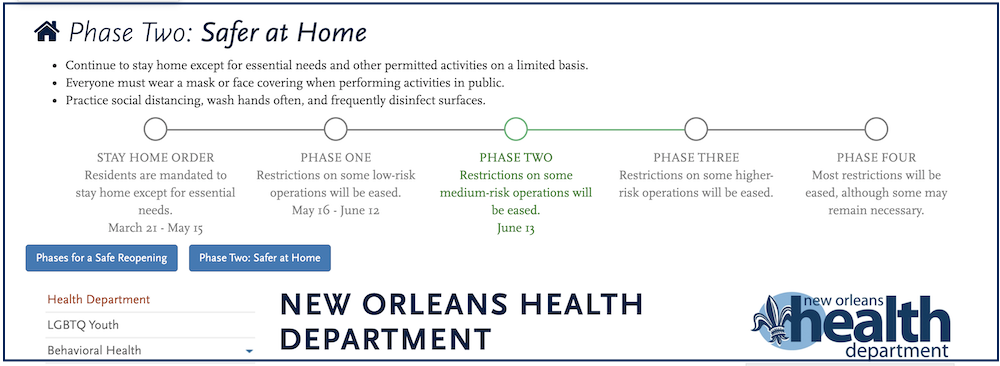

In a paid full-page letter to "Madame Mayor" published in the Times-Picayune/New Orleans Advocate in mid-April, three prominent businessmen implored Cantrell to scale back and allow businesses to start to reopen by May 1. Brushing off the criticism, she instituted a mandatory mask order as part of a phased re-opening to start May 16.

New Orleans with a 59% Black majority is a blue city in a red state. Thirty miles north, across Lake Pontchartrain in St. Tammany Parish (county), people without masks went shopping; Beau Chêne Country Club had loud pool parties and crowded tennis games, as if the horror show of deaths and closures in New York City was a sci-fi move. Trump wore no mask, why should they?

As the city's tourist-driven economy plunged, Cantrell stepped up press briefings, allowing Avegno, the political unknown in surgical scrubs, to review data and emphasize policy on reducing viral spread. Avegno gave Cantrell a valuable asset: political cover.

"Avegno has the mayor's back. They reassure people by not contradicting each other," said Silas Lee, a prominent pollster and Xavier University sociology professor.

"It's not like Trump contradicting Dr. [Anthony] Fauci," Lee said. "We've never had to live through anything like this. Avegno has a stabilizing focus on medicine. The mayor's poll support has held steady. They're both mothers, and they bring a level of compassion on the dynamics of raising a family that people want."

Protesters in New Orleans gather May 30, mostly wearing masks, in response to the May 25 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. This was during the New Orleans' Phase One of reopening: "Restrictions on some low-risk operations will be eased," which lasted though June 12. The city is now in Phase Two. (CNS/Reuters/Kathleen Flynn)

A Catholic, less conventional, family

Ashton and Royann Avegno come from Catholic families with deep local roots. Their daughter Jennifer was born in 1972. Eleven months later, Royann had a stillborn infant; the couple learned they could no longer conceive. Thus began a series of adoptions that defied conventional logic of family values, particularly in leafy River Ridge, an enclave of Jefferson Parish, the white majority suburb where the siblings grew up.

Avegno goes down the list. "My brother Ashton III, we call him Benjy, is 45 now, with a family across the lake. Greg, 43, adopted from Korea, is married in San Diego. Jeremy is biracial. My parents adopted him from foster care; he lives in the area with his fiancee." Meg, 41, also biracial, does property management work in the metro area.

"We wanted a large family," said Royann. "But after Jen and Benjy, we realized that a shortage of babies meant the end of adopting infants that looked like us. The Children's Bureau was placing babies from Korea. That's how we adopted Greg. Had we known what we were in for with the younger ones, we might have run the other way. Sometimes God keeps you ignorant for a good reason."

The Avegnos became a word-of-mouth item among judges, social workers and agencies trying to place handicapped youth without homes.

Katie, 11, had cerebral palsy when she came to the Avegnos from a Hong Kong orphanage; she died at 26.

At 12, going out to eat with the family, Jen Avegno "was mortified with this traveling circus and begged my mother to let me eat on the other side of the restaurant. They were like Brad and Angelina before it was cool. As I got older, I realized what a gift my childhood was. I shared a bathroom with six people. I am incredibly grateful that I did not have the typical American upbringing."

Her brother Matthew lived to be 14. His problems were so unique that she wrote a paper about him in medical school with a geneticist at Children's Hospital.

The youngest, Gabrielle, an African American girl of limited movement, was reliant on a ventilator and feeding tubes. A local judge had asked if they would take the baby, knowing the odds. Ashton built an elevated bed to ease the strain for Royann's monitoring. "Gabrielle was my little cloister companion," says Royann. "She contracted RSV, a common [respiratory] virus, but for a child like her it was fatal."

The Cathedral-Basilica of St. Louis King of France and a statue of Andrew Jackson in New Orleans June 3, 2019 (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Gabrielle died at 2 and a half, in 1987. A high school sophomore, Jen watched her mother function as a de facto physician.

The baby was barely buried when Royann took a phone call from a man who boldly identified himself by name as a member of the Ku Klux Klan and asked if she had sufficient fire insurance. Racial slurs were scrawled on the driveway, and teenagers made calls that used the "N-word."

"River Ridge is not a bastion of diversity," Royann said. "For the most part, people, at least to our faces, have been very kind."

Jennifer's folks still live in the empty nest house. Ashton is a semi-retired structural engineer; Royann retired several years ago from teaching religion in the city at St. Mary's Dominican, the high school both she and Jen graduated from, and where one of Jen's daughters is a student today.

Royann's teaching began as the unorthodox child-raising ended. After filling in for a Spanish teacher felled by a stroke, she was asked to teach religion. Royann took theology classes at Loyola University, New Orleans.

As Jen was reading Gustavo Gutierrez's A Theology of Liberation at Notre Dame in South Bend, Royann drew inspiration from learning about the martyred El Salvador Archbishop Óscar Romero. She showed students the 1989 biopic "Romero" in a social justice course she designed, using papal encyclicals, like Rerum Novarum by Pope Leo XIII, which promotes organized labor. "Some parents were very conservative and called me a communist. The school backed me."

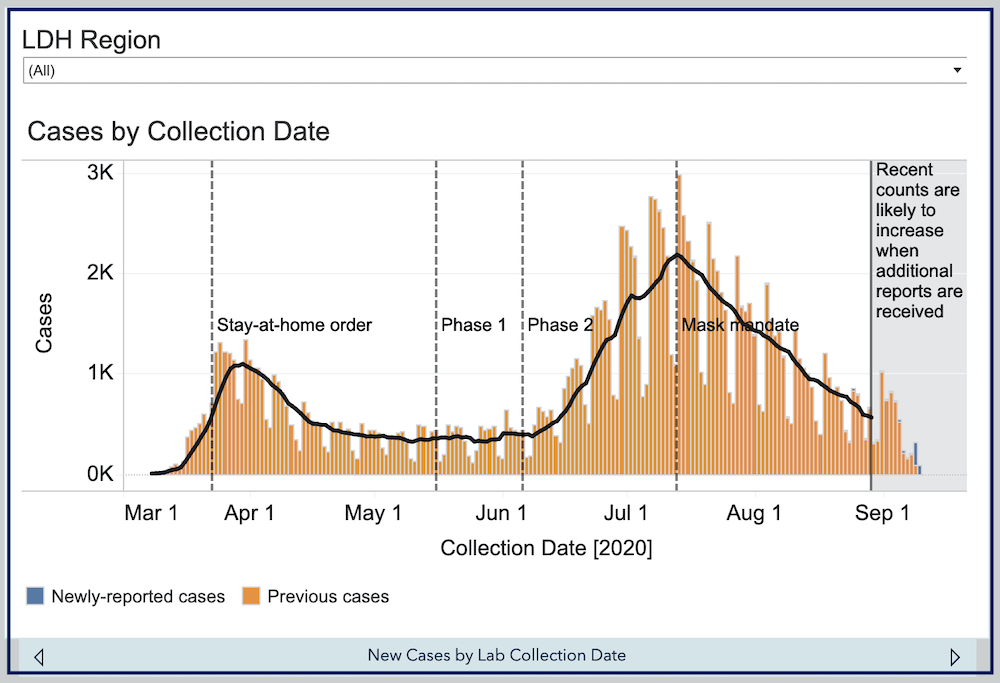

From the Louisiana Department of Health website, coronavirus cases by date (NCR screenshot)

As Congress's emergency relief funds provided a thin safety net in New Orleans, Avegno felt an easing of pressure over the tough policy. By mid-May the city showed a sharp decline in coronavirus cases. But as summer unrolled, and Trump flouted scientific advice, cases surged across the South.

By July 28, Louisiana had 111,038 cases, and 3,700 deaths. The surge had come from areas of the state where Trump's disdain of science was popular; Edwards' closure orders were not. Yet by mid-August, as America exceeded 4 million cases, Louisiana's infection rate began a steady drop. Media coverage of the pandemic had legitimized Edwards' protocols.

"New Orleans still has the most stringent coronavirus restrictions in the state, including the full closure of all bars," The Times-Picayune/ New Orleans Advocate reported Aug. 15. "Cases in the city have been receding after a rise that was far less severe than most of the rest of the state."

Through it all, Avegno reads to a daily email of prayer reflections from the University of Notre Dame.

"My day does not feel complete unless I find out the saint of the day. I love reading about the saints' lives — the more obscure, the better — and finding out who is the patron saint of what, a little spark of joy in chaotic, frenzied days."

After six months of shutdown, New Orleans had a $130 budget shortfall, a crippled tourist economy, scores of businesses hanging on by a thread, an 18% unemployment rate and City Hall scrambling for funds to help renters faced with eviction.

On Aug. 20, a week before the 15th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Cantrell in a State of the City speech touted the Health Department in saying: "At the beginning of this pandemic, national models were predicting more than 1,500 fatalities by midsummer." The city had 569 reported COVID-19 deaths at that point. As of Sept. 13, the death toll was at 584 out of a total 12,169 cases.

"We peaked so hard, so fast, like New York City, but with far less devastating impact, so it was easier for folks in New Orleans to take this seriously than in the rest of the state," Avegno reflected.

"New Orleans is a melting pot, historically Catholic, a lot more like northeastern cities than the rest of Louisiana. My absolute primary goal is to keep us from anything resembling a second-wave surge as we've seen so tragically elsewhere in Louisiana. New York and Boston didn't rush to open their bars; that's how you win, slow and steady with a lot of pain. These have been agonizing, horrible decisions, but I believe history will prove us right."

[Jason Berry is finishing a documentary based on his recent book about New Orleans, City of a Million Dreams (University of North Carolina Press, 2018).]

Planned phases of reopening shown on the New Orleans Health Department website (NCR screenshot)

[Jason Berry is finishing a documentary based on his recent book about New Orleans, City of a Million Dreams (University of North Carolina Press, 2018).]